Story — The Camels of Christmas, in the shifter universe — not done yet.

On account of TWO vet visits, and one more tomorrow. Minor stuff, but argh.

Born Free

Story — The Camels of Christmas, in the shifter universe — not done yet.

On account of TWO vet visits, and one more tomorrow. Minor stuff, but argh.

*Sorry guys, I’m working on another gift short story. My intention is to put these in kindle format for ya’ll on download on Friday morning. But we have older boy home, and the routine of the house is no longer accommodated to him, so it’s taken me this long to make it to a keyboard. So, Promo post (by Amanda Green) first, gift in the evening, okay? Be good. Treat shall come in time.*

When characters take over – Amanda Green

Once upon a time, I went to the Romance Writers of America national convention with Sarah. This was not long after she finally got me to admit that I wrote. Now, I’d been writing stories for almost as long as I could remember. I’d shown some of them to friends and teachers along the way but they were for me. Written and then stored in the desk or under the bed or in the closet. It wasn’t that I was ashamed of them. No, it was more basic then that. I come from a long line of folks who thought writing was fine but you couldn’t make a living from it. So it was one of those hobbies you really didn’t talk about but you did because you couldn’t not do it.

Then along came Sarah and my ordered world was upset and all those characters I’d been holding at bay came pouring out. One of them, Mackenzie Santos, was loud and demanding and not about to wait one moment longer than necessary for her book to be written. That book turned out to be Nocturnal Origins. I had a lot of fun writing the book but figured it was a one off. So I moved on to other projects.

The only problem was Mac and company had other plans. I had only started to tell Mac’s story. Along came Nocturnal Serenade. That’s when I learned – yes, yes, I know. I’m the author. I ought to know all about my characters before I start a book. – that Mac’s mother had more than a few issues with the fact that some members of the family turned furry and without donning a costume. Then there was Mac’s grandmother, a strong and formidable woman who shifted into a strong and formidable jaguar. All that put family dynamics into a whole new light.

What I didn’t realize was that Mac and her grandmother had plans for the two books to turn into three and then four. With Nocturnal Interlude, I was forced to explore the consequences of what might happen if the “normals” suddenly realized monsters really do exist and live next door. That revelation hasn’t happened but it will, sooner rather than later, especially when there are members of the shapeshifter community doing their best to cause a civil war among their own kind. Mac finds herself in the middle of and wishing for a nice, simple murder case to solve instead having to deal with Shifter politics and trying to keep those she cares for safe.

December 15th marked the publication of Nocturnal Challenge. Civil war among the Shifters is getting closer to becoming reality. Mac and those she cares about have to decide if they will violate oaths they took and risk war or if they will act to prevent it. There is no doubt that the existence of Shifters will soon become public. The question is if it will be done in a way that doesn’t start a modern version of the witch hunts of old.

Mac Santos was supposed to be with me for one book. Instead, she’s “helped” me create a world that is still evolving. There is one more book in the current story arc to be written. After that, the world will continue to grow. There will be more books. Will Mac and company be the main characters? I don’t know. She tells me they will, at least in some of them. Me, I’m not too sure. There are other characters, supporting ones in the current books, who have their own stories to tell. All I know for sure is I’m not yet done with Mackenzie, Jackson, Pat and the rest of the gang. I hope everyone else is as pleased to hear it as I am.

*Post of the day below this one. If you’re here for feisty opinion, keep scrolling down, but keep track of what’s on offer anyway. Some good stuff.*

We Wish You A Merry Promo- Free Range Oyster

Festive greetings, O my people! This has been a great week for promo submissions. We’ve several new releases, some older ones on sale, and some lovely covers among them both (just hanging out here has made me more attentive to covers; running the promo has made me a downright snob). I’ve heard rumor that there may be listings of good books elsewhere as well this weekend *cough*MGC*cough*, so please sound off in the comments if you know of more good stuff to be found. Go, read books! Buy books! Borrow books (and return them)! Give books as gifts! Give books as bonuses! Give books in leiu of payment if they’ll let you! Tell people about good books you’ve read, and leave reviews on every appropriate outlet. Let peace, goodwill, and awesome stories FILL THE EARTH! As always, future promo entries can (and should!) be sent to my email. Happy reading!

Jason Dyck, AKA The Free Range Oyster

Merry Christmas to all, and to all a good book

A captain who’ll take any job if there’s enough money in it.

A pilot with an agenda of her own.

And a mechanic with an eye on the pilot.

The crew of the Fives Full are just trying to make enough money to keep themselves in the black while avoiding the attention of a government so paranoid it’s repealed Moore’s Law. They’re not looking for adventure in the stars… but they’re not going to back down just because something got in their way.

“Bah, Humbug.” Rada Ni Drako wants Christmas, and the rest of the world, to go away. Her fellow soldiers have other ideas. So does Logres, the one creature Rada will not, cannot, ignore. Especially not at winter’s turning.

What happens next will take Rada and her human allies to an amazing place indeed.

The pixie with the gun has come home to see his princess crowned a queen and live in peace. But nothing is ever easy for Lom. A gruesome discovery on his doorstep interrupts their plans and sends Lom off on a mission to save not one, but two worlds. It’s personal this time and the stakes are higher than ever before. With friends falling and the enemy gathering, Bella and Lom must conquer the worst fears and monsters Underhill can conjure. Failure is not on the agenda.

On sale this weekend

A wave of possibilities rolls across the land and nothing remains the same IN ITS WAKE … Dinosaurs. Dragons. Clowns. From nineteenth-century China to the moons of Saturn, from the Renaissance to the aftermath of apocalypse, these eighteen stories share one theme–change, like you’ve never seen it before. NOW, EVERYTHING CHANGES! Read stories penned by Aurora, Hugo, and Nebula Award winners, as well as up-and-coming authors, in a single volume.

Includes a story by our own Christopher Chupik

Gilead Tan and Andrea Fielding survived their stint in the military, got married, signed up to emigrate to a terraformed colony world, and went into cold sleep for the journey from Earth. While they slept, the starship got lost and settled for a different world, a wild world. Three centuries after the founding of a colony on the uncharted planet, Gilead awakens to find humanity slipped back to medieval tech and a feudal structure. Worse, the king who wants Gilead awake won’t let Gilead awaken his wife.

Michael Anderson never thought he would set foot on a world like Earth. Born and raised in a science colony on the farthest edge of the solar system, he only studied planets from afar. But when his parents build mankind’s first wormhole and discover a world emitting a mysterious artificial signal, Michael is the only qualified planetologist young enough to travel to the alien star.

He is not alone on this voyage of discovery. Terra, his sole mission partner, is no more an adult than he is. Soon after their arrival, however, she begins acting strangely—as if she’s keeping secrets from him. And her darkest secret is one that Michael already knows.

Twenty light-years from the nearest human being, they must learn to work together if they’re ever going to survive. And what they discover on the alien planet forces them to re-examine their deepest, most unquestioned beliefs about the universe—and about what it means to be human.

This book is rated T according to the AO3 content rating system.

Free this weekend

*Okay, this is Sarah speaking. The mollusc and I some communication issues, so the promo post will go up around two my time tomorrow and for the end of the year I’ll put up promo posts (mostly for other people) in the afternoon. I’ll take care to inform you at the top of those where the post of the day is — completely out-of-itly yours – SAH*

Tin foil hat or reality speaking?- Amanda Green

Approximately a week ago, a 12 year old in Arlington, TX was taken into custody after telling another student that he had a bomb in his backpack. In September, a 14 year old was arrested in Irving, TX, on suspicion of bringing a homemade clock bomb to school. On December 16th, the Los Angeles school district canceled all classes after receiving threats against the district while New York City decided similar threats made against its schools were not credible. The following day, the Dallas Independent School District, Houston ISD and others around the nation received similar threats. These recent incidents have played out against the backdrop of the horror of the attack in San Bernardino on December 9th.

I bring up the Arlington incident for a couple of reasons. The first is the level of outrage I’ve been seeing on social media that seems to be looking at the event in a fishbowl that excludes everything else that has been happening in the world of late. Yes, the boy was arrested. Yes, he was taken to juvenile detention and held there over the weekend. Yes, he was charged with making a terroristic threat (or the equivalent) and has to wear an ankle monitor until he has his day in court. Yes, his parents say they were not notified of what happened and didn’t know until they finally contacted the school and then called 911.

What the social media accounts don’t tell you is that the boy admitted he told another classmate that he had a bomb in his backpack. They don’t tell you that the school did, according to reports, try to make contact with the parents. They don’t tell you that it isn’t all that unusual to hold a juvenile offender over the weekend until a judge can determine if probable cause exists to hold an offender.

Instead, we are greeted with the “but he did it because he was bullied” and “profiling” because the boy is, allegedly, a Sikh. It doesn’t fit the narrative that the boy never mentioned his religion and the police say all they reacted to was the fact that there was an allegation that he claimed to have a bomb and he, allegedly, confirmed he had said he had one. Let’s forget that we have lived in a world since 9/11 where making jokes about bombs and guns and such things can get you arrested and EVERYONE KNOWS IT.

Forget that this happened just days after a terrorist attack that left a number of people dead or injured in California, an attack that has Texas ties.

Forget that we are talking about a young man who is, presumably, old enough and capable of understanding right from wrong and the consequences of his actions.

I’m not saying there wasn’t some amount of profiling going on. It is quite possible that it was. What I’m on my high horse about is the fact that the allegations are being automatically dismissed by a certain group of people simply because it fits their political narrative. This tendency to react based on narrative and without taking into account all the facts – and in situations like this that has to include events going on in the world around us – can wind up leading to situations that will bite us in the butt.

Which leads to the various threats that were called in to the school districts around the country. Los Angeles has been hit hard in the media because it took the approach of closing down the schools for the day instead of running the risk that the threat was real. NYC took the opposite approach. I didn’t think too much about it at the time except to wonder if the NYPD had better intelligence than had LA. But when the other threats were called in the next day, I wondered if it was time to pull out the tin foil hat.

Sure, the threats could have been coincidental. A handful of students around the country could have decided they wanted out early instead of taking finals. After all, the new Star Wars movie would be opening soon and they might have wanted to go find their places in line. But the timing and the fact similarly worded threats were being used. . . . well, just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.

The so-called rational part of my brain kept telling me there was nothing to worry about. Then there was the part trained by law enforcement officials, the part that doesn’t like crowds and always looks for other explanations for why something happens. That part wondered if the threats were simply meant to see how the local school districts, their security contingents and the local police forces would respond. That is part of intelligence gathering. Send in the threat and then watch to see what sort of warnings, if any, are released to the public and see what sort of response the authorities make to determine if the threat is real.

Fortunately for everyone, none of the threats turned out to be real. It was reassuring to see the head of the DISD and the Dallas mayor talking about how they not only conferred with DPD but with the administrations in the other cities receiving treats as well as their local police departments and the Feds. They took the threat seriously and did everything they could to make sure our children were safe. I fully expect to learn sooner, rather than later, that the Dallas threat was made by a kid who didn’t want to go to school the next day and who heard about the LA and NYC threats and decided to play copycat.

The thing is, that isn’t the sort of threat we can take for granted. Nor can we take for granted comments made by someone, and I don’t care how old that person is, that they have a bomb. In the Arlington case, 12 years old is old enough to know there are consequences to actions. Page eight of the Arlington ISD Student Code of Conduct states that:

Students have a responsibility to show consideration for the physical, social, and emotional well-being of others. At a minimum, this may be demonstrated by: Using kind and courteous language and refraining from making profane, insulting, threatening, or inflammatory remarks. (emphasis added)

Further in the Code of Conduct, threatening behavior is defined as a Group 3 Misbehavior that can be punished by emergency removal from the campus and referral to law enforcement, among other options. Group 4 Misbehaviors include terroristic threats which, duh, includes saying you have a bomb. The same responses are available to the school as well as expulsion and more. (pg. 39) Arlington ISD, like most school districts, take threats seriously. If you search for “threat” in the Code of Conduct, you will find 54 instances of its use.

This means, the student in question knew or reasonably should have known there would be consequences to his actions that day in school. Was he bullied? I don’t know but will admit it is possible. However, there are better ways to deal with bullying than claiming you have a bomb, especially when less than two weeks have passed after a terrorist attack within our shores.

I guess what I’m trying to say it is time to start holding our children responsible for their actions. Being a Texan, this is something that has been very much in the forefront of our media of late. The affluenza teen, Ethan Crouch, successfully used the defense of never having been made to know there was such a thing as a consequence to his actions to avoid prison time after killing four people in a drunk driving accident. Instead of prison time, he was given 10 years probation. Now he and his mother are on the lam, possibly having fled the country. The poor little rich boy once again is trying to avoid consequences of bad decisions and actions.

It is time we all remember there are consequences and we need to make wise choices or face the fallout. That applies not only to our personal lives but to the decisions our politicians make as well. We cannot and should not try to be best buds with those who want to see our destruction. We should not make our next generation weak by not teaching them that there are those out there who want to destroy us and by constantly telling them that they are wonderful and special and can do no wrong.

In short, it is time for our country to wake up, grow up and grow a pair again (well, at least for your politicians to. Most of the rest of us already have. At least I hope so.) Or maybe it is time to be fitted with a new tin foil hat.

I’m mostly alive, and sorry to be so late, but yesterday for reasons I can’t explain lest we all be commited, husband, older son and I felt a necessity to walk seven miles, uphill, through snow. Younger son picked us up when we realized we simply didn’t have it in us to walk back.

It’s not the first time we did this, and it was both easier and more difficult than before. Easier in that I really didn’t get tired till the last mile, more difficult because we did it in ice and snow, and like a right berk, I forgot to wear my snow boots, so that last mile I had to go baby steps and in waddle mode, which made my ankles hurt like living h*ll.

Of course it’s also 4 years since we last did it, but I must actually be in better shape than I was then, as my legs hurt like heck today, but the rest of me is not that TIRED.

Several take aways, of course, and part of the reason we did this is that we haven’t been exercising as we should and this was sort of our opening salvo warning to the body we’ll be doing more stuff (yes, we probably DO do it backwards. Deal.) and our assessment of how bad the situation is.

The answer is both not that bad and dismal. Not that bad, because we can still do this stuff, though it takes us longer, and our legs hurt the next day. Dismal because heaven forbid we had to actually walk any distance, say, because the highways are clogged with cars fleeing the city.

When I was young and in college, I went to college about 10 miles from the house, and periodically, when the weather was fine and I didn’t need to have stuff done right that moment — say twice a month — I’d walk all the way home. Now this was ten miles as the crow flew, probably 12 to 14 otherwise. But here’s the thing, in my grandma’s time when walking was the main form of locomotion for those not rich enough to own a carriage, people walked six to seven miles regularly, for jobs, for studying, for recreation even.

Which brings to halfway through walk, older son said “you know, this is what we evolved to do. We’re not faster than most of our prey, and we don’t have the claws and teeth to bring them down. What we are is relentless. We would follow herds day and and night, not letting them rest, until the weak and the elderly fell behind, and then we had them. Hunting bands survived this way. This is what they did.

Which brings us to the long march through the institutions. In a way when the left started its long march through the institutions they were just practicing ancient hunting practices, with Western Civilization as its prey.

Now their long march might or might not come to fruition, but you can’t avoid realizing that for people whose ideas are at best silly and at worst downright harmful, they’ve achieved remarkable success by taking over what they could and grooming their kids to take over more.

It is not their fault that the fields they’ve completely taken over, like academia, literature, art and news reporting are escaping their grasp. Yes, sure, the fact that all these fields are in major crisis IS their fault, or at least the fault of their philosophy which, in contact in reality, doesn’t hold up and tends to make people make decisions (and national policy too!) based on the reality inside their heads, implanted there by the cult of Marx. But the thing is, without new technology to allow us to escape their grasp, we’d be stuck with the crisis AND with leftist control.

However, again, for a philosophy whose proudest achievement is the killing of a hundred million human beings (and that’s lowballing it, as Colonel Kratman says) to take over those many institutions and not to be laughed out of polite (or worse, impolite) society is a testimony to the effectiveness of the long march.

And it has been long. They’ve been at it for close on a hundred years.

Meanwhile our side seems to think we can do with the hunting techniques of cheetahs. We are not cheetahs. We are just human.

The RINOs you complain about are RINOs now but they weren’t always. I don’t know how many of you remember the seventies. The right here was kind of like the right in Europe. It assumed that in the end communism would not only win, but DESERVED to win, and what the right disagreed with was the way to get there. It is useful to remember this was a time when William Buckley’s dictum that conservatism was “Standing astride History yelling stop” found deep resonance. Unpack that phrase. It assumes history comes with an arrow, that it’s not going our way, and that at best we can get it to pause.

Those RINOs who, by the way, took immense flack back then were as conservative as anyone dared to be. Because everyone knew in the end the reds won.

Then the wall fell down and we knew what true horrors lurked on the other side.

Individuals process these things fast enough. Well, my generation, at any rate, awakened by Reagan and shown that the win of the dark side was not inevitable, was more pro-freedom than people ten years older than us.

But when we saw the wall fall down, it pushed many of us further into the liberty side of the isle. Not only wasn’t a communist win inevitable, but their vaunted “strengths” like superior planning and better minority integration didn’t exist unless you really wanted to plan for three million size thirty boots for the left foot only, and integration meant grinding the minorities very fine and spreading them in the soil.

However cultures aren’t individuals. Cultures re-orient and process startling events very slowly.

Yeah, those older Republicans are still with us, and they were over 45 when the wall fell, which means they couldn’t reorient anymore. (Studies have been done.)

Because we tend to draw our leadership from the older people whose “turn has come” that means you get a lot of those older Republicans.

It doesn’t mean the party is dead. The fact that there is strife at all means some of us have stopped standing astride history yelling stop and are busy building new roads for history to run on: only this time faster, better, and with more freedom for as many individuals as possible.

Yeah, we’re going to “lose some” via our “elites” i.e. the grand old men in the party betraying us. This is not their world. Reality changed too fast, and they don’t get it. But their time is limited and we can work harder to replace them.

Look, at least it’s not like traditional publishing where most of them are singing “If you’re happy and you know it” while washing down the drain, and the only house that will save itself has long been an outcast.

There is strife. Strife means the old blood and the new don’t agree. Another way to look at it is renewal.

Problem is advocates of liberty are about as good at coordinated action as a bunch of cats. I pretty much laughed myself (Physically) sick when I read that the Sad Puppies “strictly enforced slate voting.” Not only did the numbers completely deny this (the only lockstep voting was no award) but the idea of anyone on our side doing anything “lockstep”just about… Giggle, snort.

If you told most people on our side “you have to do it this way, it’s the only way” you’d get “Who’s gonna make me, you and whose army?” And if you said “you have to do it this way or we’ll kill you,” you’re still likely to get “You’re not the boss of me.” We should have “Stupidly individualistic” stamped on our foreheads.

So long, coordinated marches like what the left (they of the collectivist will) executed are really impossible for us.

On the other hand… On the other hand, we seem to do pretty well in our long uncoordinated march of building under and building around and building over.

We might all be marching in different directions and to the tune of a different kettle of fish, but the other side is so profoundly incompetent, that even so we can still replace the moribund institutions they took over.

It’s just going to take a little while. Not a hundred years, but probably twenty. Not three generations, but one and a half.

In the end we win, they lose, but you can’t stop when your ankles first start hurting.

The last mile of the long march is always the hardest one, but the goal is almost in sight.

Be not afraid.

Sursum Corda.

This morning over breakfast I was thinking of what used to be considered enough. (Not enough food, I had two poached eggs for breakfast, something that would have been un imagined luxury some days of my childhood. You see, when the chickens weren’t laying much, an egg and some rice might be dinner and certainly not every day. Of course, when they were laying and we had a few who did two eggs a day, grandma would be begging us to eat eggs. The problem of self-sufficiency at least in places with no refrigeration is that it’s often feast-or-famine.)

I was thinking that, along with being possibly the most wealthy/pampered generation in history we’re also the most demanding. On ourselves, on life, on those around us.

(Look guys we’ve been broke. We had a year we were so broke we NEEDED those donations the fire department makes for the holidays, which reminds me, the snow interrupted me, I need to make a big canned food shopping trip and take it to the Manitou Springs fire department. BUT by historical standards, I was magnificently rich. We could eat at least one meal a day, I had heat and light and plenty of water. Oh, and books and entertainment at the flick of a button. Rich.)

Specifically, as the 30th anniversary of our religious anniversary looms, and Dan wants to go away for a writing vacation for three days, (and I’m afraid people will die during it, again), I was thinking of how our marriage has been for thirty years.

Overall, it’s been d*mn nice, with occasional episodes of grumpiness (right now mine over finding/buying a house.) And then I thought by the standards of the village — the standards I heard my mom and her freinds judge marriages on — we’re a frigging miracle and fortunate beyond all hope.

As with everything else that’s a transition/change, 2015 was rife with divorce in my extended friend circle, and it seem like almost all of them got divorced because “he doesn’t make me happy” and “she doesn’t fulfill me.” A tall order.

In the village a successful marriage was as follows: he doesn’t drink, he doesn’t beat her, she doesn’t sleep around and she manages the house and keeps the kids clean.

Were some marriages hell on Earth? Sure, from the outside some looked like it, but you now what, sometimes you got these rare glimpses from the inside and realized these people were crazy but in a way they were happy too. Okay, a crazy way. But you know, looking around now at my friends who have marriages I don’t get and which TO ME would be hell on Earth, it’s not markedly different, even though everyone seems to demand so much more of marriage these days: a lot more beyond companionship, mutual support and not doing bad things that affect the other. (Yes, I know, some of you got divorced on that last clause, and that I totally get.)

But it’s not just marriages that are affected. It’s like because of mass media, those of us who tend to be driven have these impossible images of what “success” is.

Oh, it’s not just the media, mind, though it doesn’t help. Some people always expected a lot of their close relatives.

At one point my mother was complaining to a friend that I never won most of the writing contests I entered (thinking on it, there was a political color bar, of course) and how my brother only won poetry contests that didn’t pay, and her friend told her “Think about it, woman, what are you complaining about. They aren’t on drugs, they aren’t bringing you home illegitimate children, they pass their schooling with As or Bs, and they’ve never been arrested. You should be thanking G-d instead of griping.”

Now, I’m the last to encourage low expectations. (Ask my kids. I know what they’re capable of, and won’t be happy with being fobbed off with a token effort.)

However as I was thinking of that overheard conversation and of the definition of a happy marriage in the village, I realized I’m holding myself to a crazy-impossible standard. You know, EVERYONE is supposed to be buying my stories. I should be bigger than J. K. Rowling. I should be writing a lot better and a lot faster. I should be losing weight (well, that part… eventually we’ll figure out why it isn’t happening and I’m inexplicably gaining. BUT… It doesn’t seem anything I can do.) Dan and I should look like those Hollywood couples, and have everything and never snap at each other…

And I realized it’s not sane. It’s not happy-making. Not that I ever contemplated divorcing out of dissatisfaction, or that I’m dissatisfied, but mostly I’ve been very upset at myself.

I’m not one to encourage low expectations. But sometimes knowing what the passing grade is makes you realize you already have an A, and stops you driving yourself crazy.

This holiday season give yourself and those you love permission to be less than perfect. And celebrate what you have.

Every culture has myths. For instance, I grew up in a culture where I knew (not thought, mind you, knew) that if you took more than one aspirin at once, you’d die.

Proven? You don’t need proven. Everyone knew this. Why would you test something that could kill you?

So my first week in the states, when I told my host mother I had a headache and she said “just take a couple of aspirin” I thought she was trying to kill me. She had to show me the instructions on the bottle.

This trivial incident was my first exposure to the idea that “what everybody knows” can be wrong.

Progressive culture in the US, having been the dominant culture in media/entertainment and the news for the last 100 years at least (not the dominant culture in the country, necessarily, but the dominant culture in the classes that controlled these intellectual products and which were consolidated/made uniform by the “mass” aspects of communication since at least the end of the nineteenth century) has lacked challenges to its internal myths, which means it ended up with as many unfounded “everybody knows” as a small village in Portugal where aspirin was still a miracle drug and a little scary.

I normally don’t pay attention to what Bernie Sanders says, and pay Hillary only the attention necessary to roll my eyes at the things that come flying out of her mouth. (Like, for instance, that Republicans don’t know that terrorists use guns to kill people. Oh, lady, we know, that’s why we want guns of our own to defend ourselves, because the terrorists, you know, aren’t likely to obey gun regulations.)

But yesterday Mike Rowe went after Bernie Sanders.

At first I just read it wishing that popcorn didn’t have so many carbs. Then I went back and read the tweet that inspired Mike’s take down. Here it is in its full glory:

“At the end of the day, providing a path to go to college is a helluva lot cheaper than putting people on a path to jail.”

Mike got seriously upset — as he should — at the notion that not going to college is the same as being condemned to becoming a criminal, and he went after it, as well as after the fact that absent a few professions (and the only reason my kids are in college is because they’re aiming for two of those professions) college really doesn’t help. (Make an informal count in your head. How many of your friends with degrees work at anything even vaguely related to their degree? And don’t tell me “but they learned to learn” because this is another thing altogether and you might have confused cause and effect.)

But there’s more than that in that tweet, there are at least three warring myths, all of them so central to what liberalism once was that the current progressives aren’t even aware most of them have been disproven by the real world tm. These are things “everyone knows” and why would you question something everyone knows?

The thing is outside their world, where no one gives a good goddamn about their myths, these things are disproven, and most people only don’t realize it because of the entertainment news industrial complex repeating them so often and acting like they’re proven.

The first and most basic myth, and one of which, once upon a time, I was an ardent proponent, is that education is transformative. This goes along with the myth that man is infinitely perfectible.

The liberal — back when liberal meant classical liberal — as undertaken by our ancestors, hinged on the idea that education would transform everyone into individual thinkers and philosophers like themselves. It would make them more moral too and improve them to be onto like angels.

They had a point of sorts, in their time. Most of the people who weren’t learning weren’t learning because they were underfed, too busy making a living, sick with a million little illnesses that made them not function well intellectually.

I saw this in action in the village, which is why I was an ardent believer in this myth. Giving people education truly uplifts them if the people giving the education also provide a meal and clothes.

The thing is, it’s one of those things that has huge gains up front. “Teach everyone to read.” And yes, can make for a more moral society, if the education has a moral component. This is important as “education” is not a neutral value. It can be adaptive or maladaptive to reality.

However just about every country in the world that isn’t in dire crisis or doesn’t belong to a religion that forbids secular education has free education — yes, even where I came from, though often the kids were taken out of fourth grade to work in factories. This was strictly speaking illegal, but you could always find a doctor to sign a paper saying your kid was educable mentally retarded and couldn’t learn any more “abstract stuff” but could learn to be a factory worker) — at least through 9th grade and often through 12th.

I’ll pause here to point out that when I was little, someone with a 9th grade education was accorded the respect here given to people with Masters Degrees. They were learned and performed work of the mind, and didn’t dirty their hands. This I’d guess is true for most of history. The level of a 9th degree education allows you enough to explore and learn just about everything that doesn’t require hands on training or specialized tutoring only administrated by professionals. (I’ll not specify which trades because it varies per learner. I can’t learn languages outside a classroom, at least a virtual one. I also have trouble with art by myself. I’d guess there’s the same problem with most things requiring labs to learn.)

So, are people made more moral? Snort giggle. Hardly. The causes for this are complex and a lot of it has to do with how wealthy our society is. Wealthy people have always had more time to get funny on morality. Other parts include a morally neutral or worse education (when the purpose of education is to deconstruct the culture that made more people wealthy and healthy than any other culture in history, while praising cultures that mutilate women, kill gays and enslave children, it is worse.)

Are people individual little philosopher kings, for all these years of education thrown at them?

I read something in a book I can no longer remember the title of, when I was researching Shakespeare. The number of people who are fluent enough readers to read for pleasure in our day is the same as in Shakespeare’s day. When they didn’t have free education, much less 12 years of it.

The idea that if you gave everyone enough food and time and free schooling they’d all become erudite and thinkers can be disproved by a stroll through your local Welfare hub. Go on, I dare you, go down and start a little discussion on Kantian philosophy.

But it’s an idea that remains a myth on the left which has lost all other classical liberal ideals (like, you know, individual freedom) but holds fast onto this idea that education will somehow make a progressive out of everyone. (Patently ridiculous as they’ve been indoctrinating several generations now, and it still won’t take the way they want. That cold slap of reality counteracts it. Which is why they advocate more cowbell.)

The other myth in that statement — and the only way to make sense out of that linkage between education and prison — is actually several linked myths:

1- that people turn to crime when they’re poor (an insult to every poor but honest person ever.)

2- that without a college education you’ll be poor (Mike Rowe ably disposed of this one in the linked article.)

3- that if the government won’t pay for something it’s unobtainable because there is no private charity and also people can’t lift themselves up by their bootstraps.

All of these are nonsense. Sometimes I think people like Bernie Sanders watch Les Miserables (a piece of propaganda even when it was written) and say “it’s true, it’s all true” and then see the world through that lens ever since.

Being poor doesn’t lead to crime. Wealthy people can and do commit crimes, not all of them white collar (in one of the stunning contradictions that would make their heads explode if they paused and thought about it, progressives also assume that all rich people are criminals, since economics is a fixed pie (giggle-snort) and to have more you have taken “more than your fair share.)

Lack of a college education doesn’t make you poor. I’ve yet to meet a poor, competent plumber. And I sometimes regret I didn’t learn more carpentry from grandad, instead of going to college. We knew someone who built cabinets by grandad’s method (think all manual tools) in reproduction of colonial furniture. One of those cabinets which he could build in 3 months, sold for what my husband was making at the time, as a computer programmer. I’m fairly sure anyone who knows one of those trades really well is raking it in. We’ve become a nation of do-it-yourselvers not because we enjoy it, or want to save money but because finding a competent tradesmen takes longer than just doing the best you can. (Been there, done that, have spackle on my t-shirt.)

People have managed to be educated beyond their relatives and parents without any government intervention (in fact until government stuck its nose and quotas in, there were a lot of merit scholarships. My husband did his college with them and a part-time job.)

Once you realize those myths ARE myths, Bernie’s prescription to end crime makes about as much sense as saying something like “Hit yourselves on the head with rubber mallets, increase the production of wheat.”

In fact, someone came trolling a share of this post trying desperately to keep the two things linked by yelling that it was a shame we spent more on jails than education.

Again, with the what? Nothing our government does makes much sense, but this makes as much sense as “Abolish the helium reserve. Subsidize canneries.”

What we’ve found since the classical liberal times when we thought education would uplift everyone is that education and proper nutrition and proper civic instruction does uplift some people. Yeah, there are a percentage of people out there who could/would do much better with a little help. I don’t know about you, but I make it a point, on my own, to identify such people and such situations and intervene and help when I can.

But you can lead a student to school; you can imprison him/her in it for 8 hours a day for 12 years: what you can’t do is make them learn.

The same person who was whining about that horrible discrepancy between jail spending and education spending said that you know, most criminals stop learning in grade school. I think he meant they dropped out. This is probably true, although I’d bet the reverse, that if you dropped out of grade school you’re likely to be a criminal isn’t true. It’s also insulting to claim so. For this he advised more cowbell… er I mean more free education.

The sad fact is that we’ve continuously not only dumbed down education, but tried to make it “fun” (listen, if you’re learning a language, there’s no way to make it fun. To be fluent, you need to start by memorizing vocabulary and studying grammatical structures. Neither of those is fun. Useful. Needed. Not fun.) to the point that a High School diploma means nothing, which is why the new push to put everyone to college, as if more of the same will fix the problems.

There are people who don’t learn because they have no interest in learning. Some of them might be very good at things — engines. Carpentry — that would baffle phds who are not put together that way. There are people who don’t learn because our educational system, barring active teaching at home after class, is put together NOT to teach but to keep the masses from rebelling in their pseudo-scholastic prisons.

Lack of book learning doesn’t make anyone a criminal. It doesn’t make them poor either. I think my dad’s dad had a third grade (might be fourth) education. Like younger son when he was younger, he had problems with verbal expression, and issues writing a legible hand. In those days this meant “stupid” or at least book stupid, so his caring parents apprenticed him as a carpenter. He supported his family in (for the village — grin) a more than middle class lifestyle, never that I know so much as stole a stamp, and raised sons and daughter who did better than him, and grandchildren who — weirdly — all have college educations, almost all of them (except me) in useful fields that actually make things or cure people.

The left is so wrapped up in their myths that they don’t understand “subsidize more education. You’ll need fewer prisons” makes about as much sense as “eat more fiber. Control garden pests.” Worse, they legislate based on these myths, without the slightest qualm. And then are shocked and posit bizarre theories (the GOP is holding back solar energy! The oil lobby! Eleventy!) for why it didn’t work.

And this is why our monoculture of progressivism hurts every field in which it is in fact a monoculture: education, the arts, entertainment, politics.

This is why diversity of thought is important. And why the progressives’ crazy attempts to shut down opinions they don’t agree with are … well… crazy.

In the safe space everyone believes as you do. And that’s the problem. Human beings aren’t built to be safe.

It is in the rubbing of thought against thought, in the contest of vision against vision that the truly ludicrous is eliminated and that, at least, we avoid the worst errors.

It is in not being locked up in a tiny intellectual village that real progress is made. Not the “progressive” of progressives, which fills mass graves with those humans who weren’t infinitely perfectible, but the progress that fills bellies, raises humans above poverty and makes it possible to aspire to the stars.

Real progress comes from strife and work.

Which is why they’re acting more and more like isolated, illiterate villagers in a land where myth is more important than evidence.

And why in the end we win, they lose.

UPDATE: Because the post was so late yesterday and because I have a massive outline to read (Larry Correia has outlined Monster Hunter Guardian for our collaboration and sent it to me) as well as a project to finish, I decided to let this hang until tomorrow. Thanks for understanding.

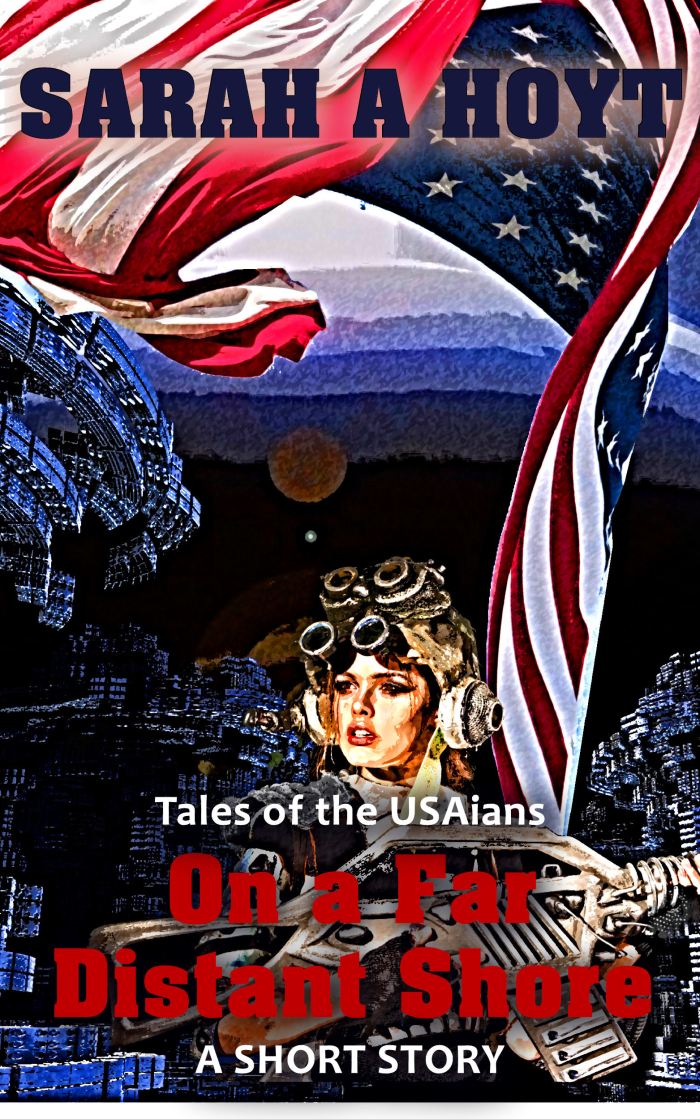

*It’s unproofed. Forgive me. Of course, it’s also free. I’ll probably clean it and sell it in a tales of the USAians collection, eventually.*

On A Far Distant Shore

Sarah A. Hoyt

It was nothing. Less than nothing. A glimpse out of the corner of the eye, a flash of color. Tell me, is that something to risk life and security on? For a stranger? And one you never liked?

I’m not a fighter. My parents tried to make me one, at least as far as their religion demanded. Weekends of camping rough and weeks of training in survival and weapons didn’t make me like it any better. I didn’t like fights, and I didn’t like camping, and I didn’t like being prepared for a revolution that never came.

And after father died, I didn’t like anything my parents had taught me. It’s all very well to believe that some supernatural force endowed humans with the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. But where was dad’s right when push came to shove? He died like other men, and they burned his remains, and he was as gone as the mythical Usa, that land of freedom that was the core of my parents’ misguided beliefs.

I was not a Usaian. I hadn’t left the religion because it was forbidden. The proclamation that anyone found belonging to the cult would be killed hadn’t made me leave. It was that I could no longer believe in it.

I’d left home, I’d trained in accounting. I was suited to it. I understood numbers. Numbers worked for me. At the age of twenty eight I was in charge of all the accounts for Good Man St Cyr, the ruler of Liberte Seacity, one of the fifty most powerful men in the world, the men who between them controlled our entire civilization, managed all our technology and kept the world in peace and prosperous.

What did I have to do with the Good Man’s body guards, or a purge within their ranks?

There had been many such. The Good Man had the ultimate right to choose who serve him, to decide who had betrayed him. His word, his choice was the final decision. There was no appeal.

Sometimes, in the hallways, I walked past a clerk, or a cleaner, a guard or a bureaucrat, shackled, between armed men.

Sometimes I walked past a little earlier, while the person who’d displeased the good man was being shackled.

Which was happened that morning. The morning that would change everything.

The man leaning against the wall was huge. One of the guard commanders, judging by the stars on his shoulders. When Liberte was colonized it had drawn from all French speaking territories, including some African ones. This man looked like he drew a disproportionate amount of his heritage from Africa. Not pure African, but a mix that gave his skin the tone of dark bronze, his very short hair a black-blue glint.

He stood with hands splayed on the wall. One of the other men patted him down. What caught my attention was the sense of tension in the man being frisked. He felt like a spring, compressed and pushed, about to lash out.

I stopped, not wanting to get in the middle of a fight. Not that there was much chance of one, as four other men pointed burners at him. If he tried anything, he’d be dead before he could take a step.

But it was no part of my pay to get in the middle of a fire fight.

The guard frisking the man removed a burner, then another, then yet another from hidden holsters in the man’s uniform. I had the impression his tension grew, but he didn’t move. Another burner and then another made a small pile on the floor. Then the manacles came out and the guard shackled the erstwhile guard commander. Another guard just stood while the other frisked the prisoner.

The men with burners seemed to relax a little. They spread out. Two ahead. Two behind, and the guards who hadn’t drawn burners, one on each side of him.

And that was when the man dropped the thing he’d been holding, somehow, in his hand. Perhaps it had been in his sleeve when his hands had been spread on the wall. But now it was grasped tightly in a fist, just below the manacles.

He dropped it, unnoticed. The men around him were expecting something else. An aggressive movement. Not a dropped bit of cloth.

I saw it fall on the polished black floor, crumpled, rumpled, a scrap of cloth. In red, white and blue.

It was a flash at the corner of my eye.

I should have walked past. I should. And I’d still be the Good Man’s accountant, with a secure job and a bright future.

Instead, I stood, rooted to the floor, staring at the scrap of cloth on the floor, barely breathing.

My mind told me to walk past. My mind told me it was nothing. Probably not even fabric. Some note paper. Some discarded insignia. But I knew what it was. I knew what it was all along.

And when the guards had vanished, marching their prisoner around a corner, I approached the scrap and picked it up. It felt sweaty in my hand, the creases marked with dirt. It was no bigger than my palm, a scrap of some ancient material displaying a white star on a blue background and a white stripe with just an edge of red.

I smoothed the creases out of it, without thinking. Mine, that dad had given me shortly before he died was just a broad strip of white with red on either side. These pieces of flags that were said to have flown, once, over the mythical Usa were both the membership symbol, the object of veneration and the promise given to every Usaian. The man they arrested had been a Usaian.

It should mean nothing. Many people were Usaians. Before the seditious philosophy that men were born free had been banned worldwide, five years ago, they’d been woven through all the structure of the seacities, all the land territories, every protectorate and satrapy under the rule of a Good Man. In the territories where they had been welcomed they’d been prominent and all but ruled.

It was no surprise that the Good Men had forbidden the religion. What was surprising was that anyone had tolerated it so long.

Since it had been forbidden, there had been captures of the religionaries. Big and small ones, and some public executions and some private ones. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of Usaians had been killed. I hadn’t been keeping track. I could even understand the rationale for the arrests and executions.

I willed my hand to drop the scrap of cloth, but it wouldn’t. Instead, exasperated, I shoved it in my tunic pocket, knowing I would be arrested or worse, should it be found on me.

The day slid by like a surreal dream. My steps seemed to loud on the polished black dimatough floor. The numbers wouldn’t add up. And the scrap of cloth on my back pocket radiated imagined heat. I felt like everyone could see I was carrying it. Everyone would know. Everyone.

I worked quietly. I probably looked absolutely normal to everyone else, but my senses were sharper, working harder than ever before. The slick, well worn buttons of the comlynk on which I worked seemed rough. The sounds around me, even my co-workers’ breaths seemed too loud.

“Samuel D’Avenir,” someone said. “A secret Usaian.” The cloth on my pocket burned against me.

I purposely tried not to hear, tried to compute the revenues from the Good man’s business at Shangrilla, but the numbers, always so easy, seemed meaningless. In my mind I saw the man named Samuel D’Avenir, and wondered if he was even alive still. He’d brought this on himself. My father had also brought his death on himself.

Then there was talk of a group of Usaians captured in Sea York, put to sea on a raft with no controls.

I realized I’d worked late, and was the only one left in the accounting office. There wasn’t anything particularly unusual about that.

What was unusual was that I couldn’t simply go home. And that I had a forbidden bit of cloth in my back pocket.

I don’t remember making a decision. Perhaps I don’t want to remember it. I found myself walking an unaccustomed way, behind the kitchens, to where the dungeons were in which prisoners from the household were confined.

My hands were sweating, my legs felt like they’d drop off, I didn’t have a burner, I couldn’t remember anything I’d learned in self defense or survival, I was going to die, and I couldn’t get my legs to stop walking towards trouble.

It is amazing how the lessons of childhood linger. I found myself thinking of a game we’d played at camp. It was called jail break. It was just a game. But the first step was to neutralize the guards. And then to neutralize the bugs.

All of it involved burners. Functioning burners.

Or not. But without burners it was more difficult, and only the bigger boys had ever won it. I wasn’t a big boy. I was a girl, who was out of shape, who came up to a meter fifty two if I wore a moderate heel and who massed 46 kilos. Maybe I could get up to 50 kilos, soaking wet.

I walked, casually, calmly, back to my dormitory. As one of the senior personnel, like the household manager and the land manager, I got to sleep in the house, in the basement. The quarters were comfortable, free, and much better than I could have afforded out in the seacity. For the first time it occurred to me perhaps they weren’t a perk of the job. Perhaps the good man gave us these quarters so we couldn’t talk about his business outside the house, and so we could be watched.

It wasn’t as though I hadn’t realized there was a bug in my room. As I said, some things you learn in childhood last forever. I’d brought out a little gadget when I first got the room, and I’d done a sweep for bugs, and before I hid what I must hide in every room I inhabited, I’d made sure the location wasn’t caught by the bug.

For the first time since then, I got a feeling I had perhaps been insufficiently cautious. It was that flag scrap burning in my pocket, making me thing of things I’d never considered before. What if that bug, which, granted, had been the only one in the room when I moved in, was no longer the only one? Since the Usaian cult had been justified, and since the Good Man of Olympus had sent assassins against Good Man St. Cyr, the Good Man had been far more vigilant, and it was quite possible this involved putting more spy bugs in the servants’ and functionaries rooms. At least in the rooms of those who had inside knowledge about the Good Man’s affairs, and who might be in the pay of his enemies.

My room was very small. I was one of the upper functionaries, but not a particularly important one. Just a number jockey whose only subordinates were data entry personnel. I rated a window, looking out over the sea, a comfortable arm chair, and another chair next to a built in desk with compartments for data gem storage, and drawers for my personal effects. Other than that there was a closet, where my clothes hung, and my shoes ranked beneath, in a neat line. And the single bed, against the wall.

The cell-like room opened to a closet-like fresher, which had all the necessities, as well as a small square unit that vibroed clothes clean.

I tried to move as I normally did, with no sense of urgency, not giving the impression of any worry. It was normal, when I came into my room in the evening, for me to change into my night clothes, before ordering my dinner from the refectory downstairs. As I contemplated what I should do, I decided it would be best not to break pattern. At any rate, the view from my window was swirling snow and the sound coming through it was the howling of wind. I realized for the first time the course I’d set on might mean going out there now. At least if I didn’t die first. So I might need my pajamas under my regular attire. I undressed, put my work clothes in the fresher and set them for deep clean, mostly because it would take a long time and make noise. Then I activated the link on my desk, and ordered a portion of today’s dinner, which is what I normally did, to avoid thinking.

I waited until the automated dumb waiter delivered it, ejecting it onto my desk from a slit on the wall. It looked like a savory soup of some kind, with a sandwich on the side. I’d never found anything so unappetizing. But I usually ate at least part of the food, so I started taking bites of the sandwich, while I opened the top drawer on my desk, and reached in to activate the bug-finder I’d hid there. It was cleverly disguised as a dictation receiver, and it actually worked as one, of course. The things my parents had given me to ease my way in the world tended to work. Centuries of refinement to make sure people stayed alive, I thought.

For the first time in years I thought of Mother. She’d stopped talking to me when I’d told her I no longer believed. The fleeting thought that she’d not stopped out of meanness but because it hurt too much to talk to me. My father had died believing in life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. He’d died believing that if you died faithful, you’d be reborn into a life a freedom and justice.

Most Usaians were Christian, and the two ideas of the ever after had melded into this idea of a happy ever after land – the furthest shore, one of our hymns called it – sort of like the summerland of the Celtic myths. And though being a Usaian didn’t even require one to believe in an after life, it seemed most people had settled in that image of the place good little Usaians went after death.

Stories to make children happy, I thought, but my eyes stung as I thought the reason Mother didn’t talk to me and returned all my remittances of money was that to her I was worse than dead. I wouldn’t meet her in the distant shore where Usaians prevailed and freedom rang. And it hurt too much for her to hear from me now.

For just a second, I considered calling her. But I couldn’t. I just couldn’t. Not now, not when I might be watched, or when the recordings of what I’d done would be examined over the next few hours.

So instead I ate my sandwich and noted that there were three new bugs in the room.

I had two choices, neither wonderful.

One was to outright disable the bugs, but that would start alarms going. Sure, there was a strong chance my room was low priority and that there was no alarm in the bugs themselves. In that case I had an hour, maybe two before some bored functionary noticed that my bugs had been killed. And even then, given my impeccable past, there was a very good chance that they would think it was some sort of systemic failure affecting my room.

On the other hand – on the other hand, depending on how many Usaians the Good Man thought there were in the house, it was entirely possible everyone was high priority and that the failure of a bug – any bug – would cause an immediate search of my room.

I discarded that option with a heavy heart, because it would have been the easiest thing.

The other thing was running the shower in my fresher as hot as I could for as long as I could. Most of the bugs in staff rooms weren’t that sophisticated, and a fog of vapor would be enough to obscure that I was blinding the bugs. Oh, I don’t mean the vapor itself would blind them. Not enough. But it would make it possible for me to put something else in front of them and be taken for vapor. The something was easy. Pieces of the blind on the window, which was supposed to diffuse the light without stopping it. And if I suspended it about a palm from the bugs, it would look like it was just exceptional vapor, and anyone monitoring would wait for it to clear before coming to investigate. Until it didn’t. And by then I’d probably be in more trouble than just blinding the bugs.

So I finished my sandwich as I turned on the shower at maximum hot and flow. This wasn’t even unusual, as I often took long showers after a day when the numbers didn’t add up right for me.

Then I sat down at my desk, ate the soup, and sent the plate and bowl down in the dumbwaiter chute.

Once the fog in the room was thick enough, I checked in the drawer the positioning of the bugs. Fortunately none of them was fixed on the windows, so I could tear out pieces of the blind, without causing alarm.

I yawned theatrically, moved to the window, pulled the blind open as though to look at the sea. While staring out at howling wind and swirling snow, I tore little pieces of the blind. Then I climbed on the window sill itself, out of pick up of the bug, and folded and tied the piece of stiff material, so that it formed a sort of little umbrella about a palm out from the bug which was a hidden in a knot in the paneling. Now having more space that the bugs didn’t cover, I could grab my desk chair to climb on, in order to disable the other two bugs with their own little umbrellas of fabric.

This left me free to get down to business. The first business was pulling the drawer of my desk all the way out, and removing the false bottom I’d put on it. At the time I’d put it in, I had thought this would never be needed. I was determined to be a good subject of the Good Men. The revolution I’d drunk with mother’s milk was forgotten. I was never going to need any of these. And yet—

As I said, the things you learn in childhood are never truly forgotten. I’d thought it was crazy, but I couldn’t feel safe without a burner nearby that I could pull out in an emergency. Make that three burners: one so called lady-burner, small and compact and with short reach; and two battle burners which were slim and light, but had the reach needed for a pitched battle.

I now strapped on the holsters that would keep the burners hidden under my regular clothes. And then I took the other thing.

In the drawer was a piece of cloth, a white strip with a bordering of red. I stared at it a long time, before taking it up, and putting it in my pajamas breast pocket. The course I was one, there was nothing safe in. Finding this scrap on me wouldn’t make me any more dead than what I already planned on doing.

The piece of flag reminded me, and I went to the fresher. Under the glare of the bugs, I’d not dared take Samuel’s piece from the pocket of my daysuit. I fished in the vibro and brought it out, smelling much fresher, the colors much more vibrant, but still the same old piece of cloth.

I shoved it in the pocket next to my piece, but I left my day suit in there. It was all too entirely possible I would need to go outside, and the work suit – pants and tunic in severe grey – wouldn’t do it.

Instead, I slipped on the dark blue, insulated pants and tunic I wore when I must go outside on some errand. It looked lumpy over my pajamas, but it would be very warm. I finished the ensemble with insulated boots. I was going to be hot as hell while inside, but it couldn’t be helped. At least I wouldn’t freeze if I had to go outside for any amount of time.

As a last minute thought, I dropped my bug detector into my pocket.

Armed and with the two pieces of flag in my pocket, I let my shower run as I got out. A careful look down the hallway showed it deserted, and I closed my door behind me, and walked as non-challantly as I could to the lower levels, near the prison.

And then it occurred to me that the game had had a distinct number of steps: neutralize the bugs, neutralize the guards, neutralize—But all these assumed you were a known hostile to the regime, and that you could rescue your friends in the open, because they were already hunting for you.

I wasn’t a known hostile. I wasn’t even an hostile at all. I just had a fellow feeling for this man, Samuel D’Avenir, and I couldn’t leave him to die without at least knowing what he had done. It occurred to me, belatedly, that perhaps he was an assassin; perhaps he had murdered people without provocation, in which case his arrest was just. But then again, maybe it wasn’t. I had to at least know.

But I didn’t have to throw my whole life out on this. There was still time to go back to my room and look like I hadn’t done anything reprehensible.

Is a piece of cloth something to throw your entire life out over?

So I stopped following training, and started thinking. One of the advantages of being an accountant for a Good Man’s house, particularly the chief accountant, is that you know everything that happens in terms of improvements and building. Among other things.

One of the things I knew was that the kitchens had got a new system of ventilation, and that the shaft for that ran right behind the cells where members of the household were confined when they incurred the Good Man’s displeasure. That I knew, at that moment, only Samuel D’Avenir was thus confined. Which was good, as otherwise it might get rather confusing.

I ran the bug checker, but the hallways here had no bugs, or at least none that my apparatus could detect.

Glad of my military burners, I took a detour near the kitchens, and – glad the corridor was deserted – burned the lock off the utility tunnel, which would have looked to anyone non-initiated as just a section of wall save for that tiny dimple that I knew was a lock. I opened it and went in, closing it behind me to prevent being followed. It was very dark in the corridor, but my eyes got accustomed and I walked around two large fans and air-purifiers, ducked under a vent, and stood in the narrow space that this ventilation corridor shared with the jail. It was a very little space, like a narrow door. Only of course, it wasn’t a door.

I tried to think of the ways I could verify that Samuel was in there, and also blind the bugs. My bug detector told me there were five bugs in there. Blinding them was essential.

I triangulated their positions, then set my burner on burn. The problem was once I blinded the bugs, we were on a timer. It was possible that it was taken to be a glitch, since the door to the jail wouldn’t open. No one who hadn’t seen the plans would think of another exit to the jail, which, otherwise, was sunk in miles of solid dimatough which built the structure upon which the seacity had been grown.

And it was unlikely – given compartmentalization of seacity bureaucracy – that security had seen the plans for a kitchen ventilation tunnel.

I set my burner on maximum heat, and set it in a position that would allow me to reach in and burn all the bugs, without their seeing me, or my hand.

Perhaps at dinner hour it wouldn’t be a great priority to check on the cell, which would give me some minutes. Not a great many minutes, but some.

It took some minutes, which was the problem with this process.

But after some minutes, there was a hole in the dimatough. I reached in, just the muzzle of my burner, and on a tight burn ray, and following the position indication of my bug finder, I burned each bug, very fast.

From the other side came a gasp, and then, “Who?”

I couldn’t recognize the voice, and I was assuming it was Samuel. At any rate, there was a way to know, or at least to know he was one of ours. Few people remembered my namesake, which made my middle name significant. But Usaians would know. “Lucy Knox Ferrant,” I said, in a whisper.

The gasp again, and then something that sounded suspiciously like a nervous chuckle, “Sam Adams D’Avenir.” And a deep breath. “Is there an operation—are you rescuing me?”

I didn’t want to give him false hope. “I have your piece of flag,” I said. I’d got the burner on cutting and was aiming for the area where the newly-set wall joined the old ones. I made an exclamation of triumph as I realized the seal was ceramite and melted really fast.

Fast enough that in minutes, I removed the panel. Samuel Adams D’Avenir helped me push it through, then almost ran into the tunnel, and stopped, confused, when I wedged the piece of wall back into place, and started melting the ceramite to rejoin it.

“We don’t have time,” he said.

“I’m hoping this will delay them,” I said. “Certainly send the pursuit in another direction. But we have time. I’m going to take you through ventilation tunnels and passageways to—”

“No,” he said. “We don’t have time to save them. I think they’re outside and exposed. Have you seen the temperatures?”

I turned around and blinked at him. “The what?”

“Our people,” he said. “Who the hell sent you? Didn’t they brief you?”

“I sent me,” I said. “I caught your piece of flag. I couldn’t let you die.”

There was surprise first, and then a sort of slumping of his shoulders. He made a sound that might have been a hiss of frustration, and then said something that might have been “merde.” “I thought—” he said. “I hoped—Our fellows in Sea York—”

“Have been captured. They were executed by being set out to sea on a raft with no controls.”

He blinked at me. “But then we are—”

“Alone and I don’t know what you were doing, but we can’t do anything. We can save ourselves. Come. I’ll take you to—”

“No,” he grabbed my upper arm. “No. Listen to me. I was captured trying to figure out where they’d been taken. I had everything ready to rescue them. I just couldn’t figure out where they put them. I know it was outside and exposed, because it’s easy for the Good Man to say he’d just detained them, and it’s not his fault if that many people died of exposure, but theirs for not taking warm clothes. Listen. We must save them. There’s at least five hundred of them. I dropped the flag so they couldn’t be sure I was a Usaian and they wouldn’t question me and find any more that might still be free here or in Shangrilla.”

“Them? Who is them?” I asked, impatiently.

“Everyone they could find who was a sworn Usaian in the two isles. Entire families. Elderly people. Babies.”

My mother was in Shangrilla and would at least be suspected, since her husband had died a Usaian. My stomach dropped. “Where? Where did they take them? And when?”

He shook his head. “When was three days ago. I got word through the circuit. Where I don’t know. I tried to hack into a link. But they found me. They arrested me on suspicion of Usaian sympathies, and the only reason I’m still alive is that my men didn’t want to believe it. I used to command them.”

I realized I’d cackled. “Come,” I said. “Come.”

Tracing the way back to my office was easy. In his uniform, which they hadn’t removed, Samuel was probably less conspicuous than I was. I refrained from burning bugs on the way, because it would just make things more obvious. Instead, I gave the bug detector to Sam, and told him to keep his face averted from those.

My office was deserted, but it wasn’t the first time that I came back to work at night. I left Sam at the door, where he looked like no more than a guard, protecting a late worker.

Then I went to my computer.

If they’d captured them three days ago, no matter how coded or how hidden, there would be fuel and vehicles detailed to the transport. And there would be food. Because executing people through weather was one thing, starving them was another. The Usaians were not easy to isolate, having a lot of sympathizers everywhere. And an “accidental” death due to exposure was easier to swallow than starving a large group of people. Word would get out afterwards. People would know.

I found it almost without trying. It wasn’t the food. It was the potable water. A vast amount of potable water sent to the old algie farming station to the North of Liberte.

I came out and told Sam that. He nodded. “I have things in place,” he said. “Vehicles. But I was hoping…”

“Yes?” I said.

“To have got some buddies of mine from the seacity, only now I’m afraid of contacting them because –”

“You were arrested. They’re probably being watched.”

He nodded. “I only need another person. I have two troop transports waiting. I set them aside, with no trackers. We were going to swoop in and take everyone to… to a place in the continent. In the old North America. We were—”

I wanted more than anything to go back to my comfortable room, to resume my routine. This was too much to do for a piece of flag.

I fished in the pajamas pocket under my suit, and brought out his scrap, and handed it to him. He looked puzzled. “I’ll do it,” I said. “I had the training. I can fly anything. I was raised devout.”

He only hesitated a second, and then he led me through an outer door, and we ran through the blind snow. Behind us, alarms sounded. They’d either found he escaped or something else had given the alarm, but there was no one trying to stop us, and no guards at the transports which he’d hidden in a warehouse area, in the lower levels of the island.

I don’t know how low, and I don’t know how fast or how long we ran, only that I ran until my lungs burned, and that he had to stop now and then, so I could catch up, even so.

By the time I entered the large transport, my eyelashes were rimmed with snow, my eyes felt frozen in their sockets, and I wasn’t sure I could survive this.

But instinct and long-learning is a wonderful thing. I handled the controls by rote and without thought, took off at a sloping curve, and made it to the skies just before a flare burst to my right, making the ship tilt. I corrected by instinct, muttered “bombs bursting in air” under my breath, and set the fastest course to the old algie station.

Before I realized I’d reached it, I started taking fire. It took me a moment to realize that Sam’s ship, just ahead of mine, was returning fire, and a longer moment to realize these were equipped with defensive weaponry.

Firing them back was harder, and I can’t tell how much damage I did, rather than helping. I tried not to fire on the main station, as I was afraid of hitting people. I couldn’t see very clearly, but when Sam’s ship floated down for a landing, I went too, landing near him.

We had landed on a vast field of snow. There was a temporary fence of the sort that is made of interlocked dimatough panels, all around. Within the perimeter was a multitude of people. I had an impression of people without number, of mother’s clutching babies, of men trying to protect children from the bitter wind, and of people fallen to the ground, either dead, or having given up.

Sam jumped out of his ship and I followed. He shouted, in a voice that could be heard over the field. “I’m Sam Adams D’Avenir. Who are the leaders here?”

It took a moment and then two men emerged. I didn’t hear their names, and I couldn’t even hear what Sam was telling them. He spoke very fast and a lot of it seemed to be references to some pre arranged plan.

While Sam was talking, a gate opened in the fence, and men rushed in, in formation. They ran towards the ships.

Sam shouted “Take people in. Take them away.” And then he was running, positioning himself to intercept the column of men coming in, shooting at them.

I grabbed my burner and did the same, as did a number of young men. There must have been burners in the transports, though I hadn’t looked, because surely the prisoners hadn’t been armed.

There weren’t many of us, but there were enough to stop that column, and make it to the gate, before another one came in.

I sealed the edges of the gate, which were ceramite because it was hard to make moving parts in dimatough. Or at least it was hard to make them with any degree of precision.

Sam had climbed up on something, on the side of the gate, and was shooting down. I found the same footholds, part of how the gate was put together, and leaned over the fence. There were masses of Good Men guards charging the gate, throwing shoulders against it.

Other of the young men helping us, had climbed up on the fence and were shooting at these men. The men shot back, and if you failed to duck fast enough you’d get killed.

I realized I had engaged in battle, and in ducking, when my burner ran empty. I was handed two, as I turned around. A young man had salvaged them from the corpses now inside the gate, of the men we had killed to get to the gate and close it.

It seemed surreal to have killed so many people, but I hadn’t had time to think, and none of it was more than a feverish dream. Behind me there was the sounds of people being herded, very fast, into transports. Shouts, screams, babies crying. In front of me, there were people to shoot at, and the other defenders standing with us were shadows in the snow. My trigger finger hurt, as did my eyes. My hair was crusted in snow, standing all around me, a frozen bramble.

“Why aren’t they attacking from the air?” I shouted at Sam, who was nearest me.

“Because I made sure I burned all their fliers. They’ll get new ones,” he said. “But hopefully not till our people are out of here.”

“They must be calling for help now,” I said.

“They are,” he said. He looked over his shoulder, then shouted in that voice that he must have learned in command school, the voice that could be heard over the sounds of a rushing multitude, the sounds of battle, “The rest of you go. The ships are almost ready. Go, you fools.”

I looked outside the gate. There were too many men there, too many men shooting and rushing at us. If we let them get close enough to the gate and stay there, so they could melt the hasty seal I’d made on the edges of it, they would come in. They would overwhelm us. They would stop the transports and evict all those men and women and children, all those elderly people.

From somewhere behind near the transports, a voice called “Come on you fools. We’re taking off.”

There were sounds of rushing footsteps, sounds of snow kicked up, sounds of feet on embarkation ramps.

I wondered if my mother was in the transports, if she’d avoided capture, if — If she knew. If she knew I was here, and guarding the retreat.

“Go,” Sam shouted at me.

But there was a bright boy near the gate, applying burner to ceramite, and there was no way Sam could burn him at that angle. So I burned him, and the bright boy that took his place, and I called out to Sam, “If I do you’ll be overwhelmed before they take off.”

He said something that might have been swearing, then he shouted back, “I wish—”

“Yes?” I said.

“I wish we’d met before this,” he shouted back, and there was something like laughter in his voice.

Behind us, one transport took off. Sam’s shooting slowed down. I looked an noticed there was red all down the arm of his tunic.

The second transport took off.

***