In the scattered files on this computer — and partly in handwritten notebooks in my office closet — there is a halfway written novel called The Years Undone.

It’s about the Red Baron — No, not the one where he’s a dragon shifter. I don’t know why I have two completely different novels with the same historical person. It’s not the first time, though — and therefore by extension about World War I. Or at least the aftermath of WWI. It is actually not a coincidence that I have two novels with that character, and another novel planned set in an alternate World War I.

For years, World War One was one of my reading obsessions. (The French Revolution too, but I had to give that up, because it made me so depressed there was nothing to do.)

World War I is the glitch in the matrix that haunts most historians, the place where it looks like Western civilization went wrong. The place the thread broke that was leading us through the labyrinth of barbarism towards the light.

Oh, it is an illusion, you know? It looms that large because it’s close up and in our face. humans have done stupid, inexplicable things before, and there have been many times where history seemed to stutter, veer off from a course that made at least some sense and go howling in the wildnerness for a while, at a cost of the some large percentage of the population: the English civil war, the 100 years war, the Moorish invasions, the–

To us it is World War One that looms large, partially because it hasn’t been fully digested. In historical terms, world war one was yesterday. We witnessed what seemed like senseless carnage on a massive scale.

Western civilization has been bleeding out from a wound sustained on the fields of Verdun.

But that’s not important right now. Or maybe it’s the only important thing, but it can’t be approached full on, or we can’t face it. So we must pirouette and tiptoe and dance a gavotte towards it.

Which is why the years immediately after WWI make such rich reading: histories, biographies, mysteries (which by their nature are a literature of the quotidian, at least cozy mysteries) and books of musings.

I found the title “The Years Undone” in poem by one of the poets of WWI. I no longer remember the poet or the poem, except it was a musing on how he wished the years undone in which he’d fought in the trenches.

Heinlein had a remarkably similar sentiment in Time Enough For Love. The file clerk that passes for my memory is confused today but I believe Heinlein called WWI “the War where both sides lost.”

And that’s a good way to see it. Another way to see it is that humanity lost. Afterwards, the world took a path of ever increasing government power, increasingly more regimented life, and a drive — partly fed by Russian imperialism — towards ever more “internationalism”.

Erase that. That’s what you’ve been told, but it’s not true. WWI was the first gasp of internationalism. All those royal families with their tentacles reaching into other countries, all the striving of cousins and brothers, uncles and nephews.

And the dead in the fields, the cadavers of young men piled in French and Belgian fields only fed the internationalism because somehow what propaganda made of that senseless war was that the fault was of NATIONALISM and of individual striving.

Which brings us back to the times. The times were the apex of the industrial revolution, when mass industrial production, communication, even art reached its peak. There was nothing anyone could do to fight that. You see, I’m not a materialist. I know there’s more to the world than the material, money, how we live.

But I also know that men — and women too, if you’re one of those that doesn’t realize men is inclusive in this case — live according to their understanding of the world and their material culture at that time. Elizabethans believed in a clockwork world, and primitives believed in a universe that worked by sympathetic magic. Some days I suspect we still do, but that’s something else.

The world of World War One and the dawning 20th century was one of increasing concentration of resources, and standardization of resources and manufacturing and, really, all production. Which brings us to the wars and what led to them….

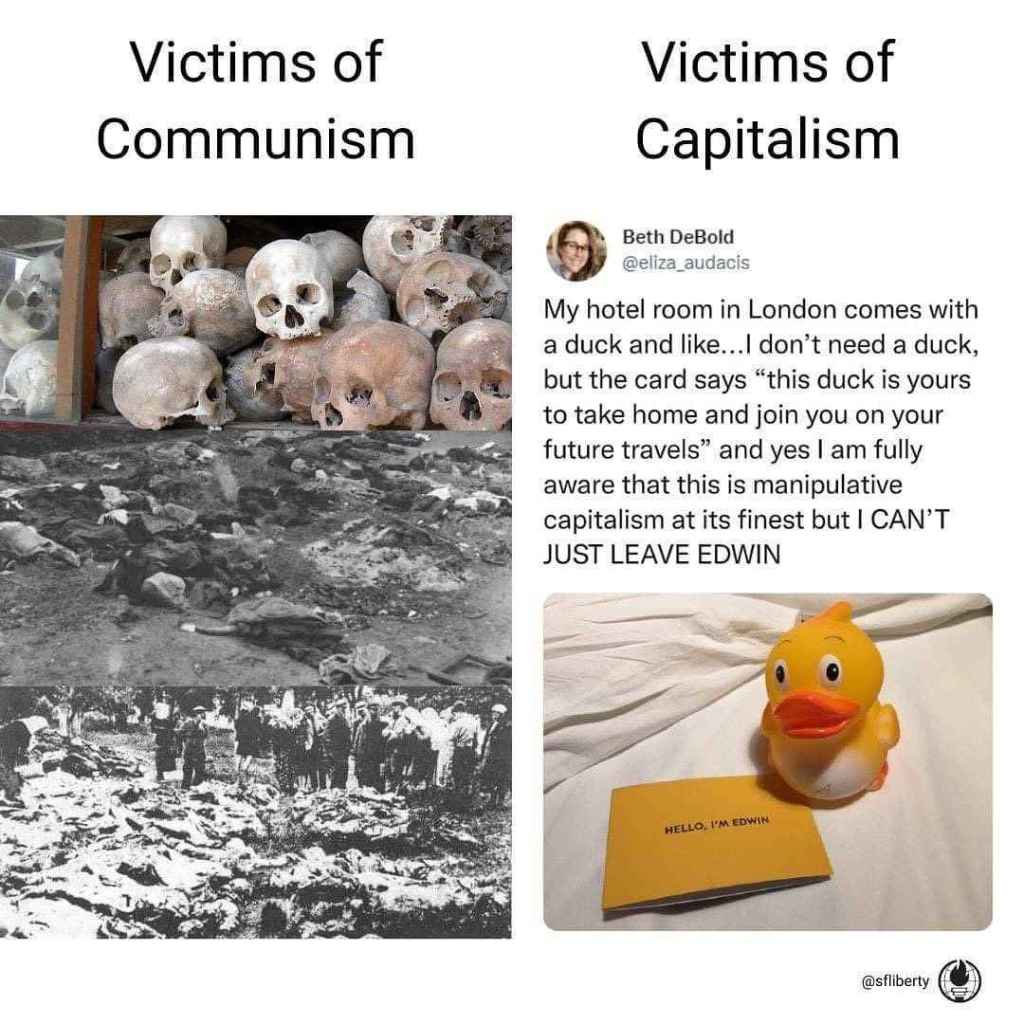

The “systems” of the 20th century were systems that treated humans as widgets, as groups, as playthings. Communism, fascism and the dilute versions of both that the West installed in its supposedly free societies were all attempts at top down control, at “scientific” governance that controlled everything from the economy to the daily life of every human under them.

…. They’ve been falling apart for 100 years, and it’s become obvious they were falling apart at least 50 years ago. Because humans aren’t widgets and humans don’t work well when treated as widgets.

The country that retained the most freedom was the US because that was how we were founded, from the beginning — and our very founding is an affront the rest of the world will never forgive us — and we were also the most productive and the most innovative.

Even hampered by the fascist shackles that FDR clapped on us, we’ve produced enough to keep the world going through the delusional hell of the 20th century. We’ve innovated enough in all fields to show that the idea of top down control is a delusion. A dangerous one. And now we’re shaking off the shackles and the morbid dreams of the past.

We’re going to have to invent our way out of this, to pave the road so other countries can follow. But that’s okay. That’s what we have always done. (And what other countries can’t forgive.)

Do we wish the years undone of the 20th century, the years when we’re now finding, in many ways we were fighting ourselves in the dark and the fire? Or at least financing those who fought us and hated us?

I don’t think it can be undone. As with mistakes in individual lives, the mistakes made in the long history of humanity are part of who we are, what we’ve learned and who knows where we’d be without them. What we did was because that was how we understood the world. And now we understand it differently, but we wouldn’t be here now if we hadn’t been there then.

Or if you prefer, supposing the US had stayed out of WWI? Would that mean that the bitterness of the 20th century wouldn’t have touched us? Oh, hell no. It means we’d probably have come up — as the rest of the world destroyed itself — with some ultra special, invincible philosophy of mass, top down governance that actually destroyed us and what remained of humanity.

Sure, we could have sat out of WWII and let someone else come up with atomic weapons and– And the first use would be likely to be mass industrial and truly devastating.

Even through the cold war, by existing, we gave hope to the world, and we created a doubt that the USSR was inevitable. Oh, sure, we too fell to their lies, and we supported them in their fight more than we should have.

But had we not done that, I suspect the USSR would have eaten the world. We’d all be Africa in the late 20th century (And there’s fodder for nightmares.)

Of course, there might be a path through that got us to where we’re now without the horrible losses, the psychological damage, the hampering of the 20th century.

Only I doubt we could find it, because it would require us to be perfect and have perfect knowledge. Until humans are angels, that will never happen. When humans are angels, we won’t need that.

It is silly — and facile — to say that we live in the best of all possible worlds. that’s not the way the world works.

To say “if we hadn’t done this, we wouldn’t have this good thing” is a fallacy. It’s the survivors bias. We survived, therefore this is the best of all worlds.

But here’s the thing, worse things could have happened. Far worse. It won’t take much thought to realize it.

And the path where nothing bad happened requires than we know then what we know now.

The Years Undone is a time travel novel. Where the characters are pulled forward, unwilling, and then miraculously find a way to travel back with the knowledge.

This is because, when it’s finished, it will be a work of fiction. In reality we’re not granted such things.

And therefore we don’t know how things will end. Human society is a series of experiments, surging forward and falling back, then learning, integrating and moving forward again. The same way a human lives and learns and grows.

It’s not ideal. It’s a consequence of what we are and how we work. And we can’t be other than we are.

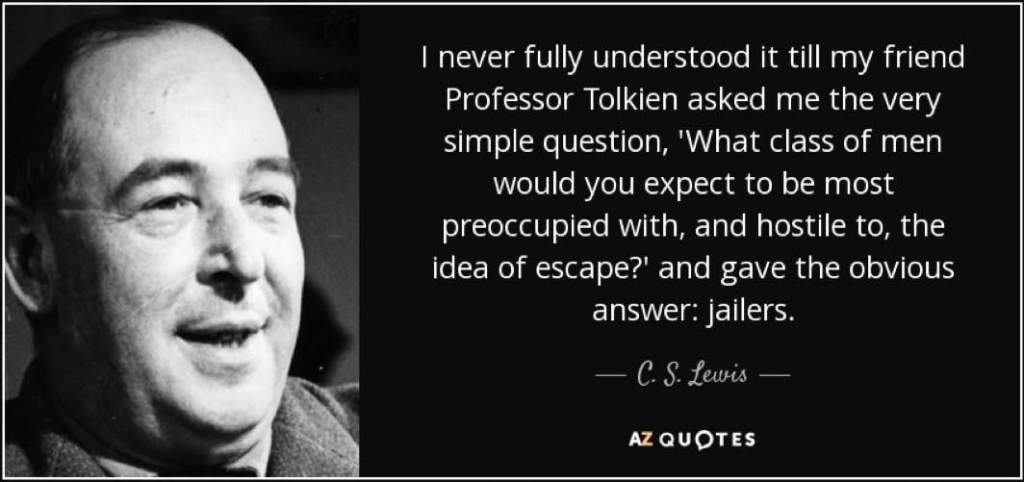

So, what can we do? We can fight, with words, with deeds and, yes, sometimes with weapons for what seems to maximize the potential of humanity and our capacity for good: Individual liberty and small, responsive political units. (Partly because small political units means that there is less damage when things go wrong.)

We write, we fight, we think, we speak in favor of humanity and against the hatred of all that’s human. We write and fight and stand for liberty and its fruits: free creation, love and a lot of fat and healthy babies. Oh, and beauty, which frankly is an attribute of all of that.

And we go on. Where we are, with what we know. Sure, maybe in 20 years we’ll realize we were wrong, and our goals unworthy. But then we readjust and fight again.

Because it’s our only hope, the hope for the future. The hope for humanity.

Go. Forward only. The past is a dead country and those battles not worth fighting over.

In the future there’s hope and there’s glory. Oh, peril too, but if you don’t overcome peril, what is triumph worth it.

We are living in a very exhilarating moment where the horrifying darkness of the twentieth century mass everything and top down control is receding.

Stand in the light and fight for freedom.