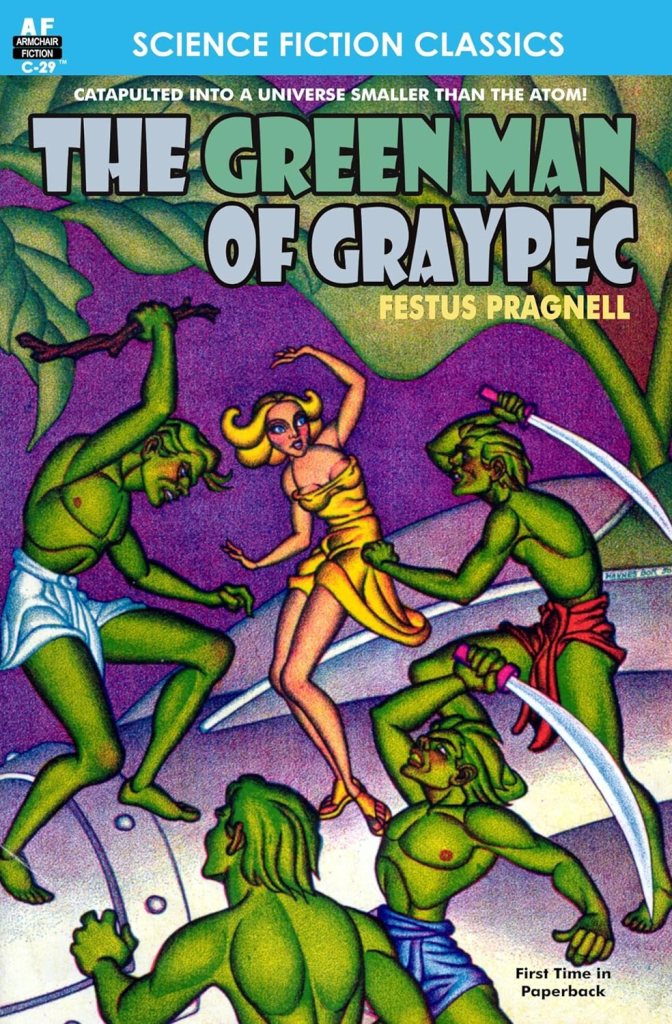

And in my reading myself back through my own origins in science fiction, we now come to number two in the Coleccao Argonauta that formed my childhood reading: The Green Man of Greypec.

Before I go any further let me point out that the next book up is City At World’s End by Edmond Hamilton. Tuesday or Wednesday next week, depending on the state of revision, snot, etc.

So, now we’re to the Green Man. When i revised it in 2016 I was profoundly upset by a bit in the book about eugenics and socialism. This time it didn’t bother me at all. See, before I read (re-read, though i only had the haziest memory) it I read the author’s biography and found he was an enormous fan of H. G. Wells, so of course he would pervaded by early 20th century socialism.

To get past the intro: the book was first serialized in 1936 (and bears the marks of it) but revised in 1950 for book publication. I’d say still being in print almost 100 years later, and people (not just me) still talking about it is a good run.

The book was written by a British police clerk. Festus Pragnell, the author, actually wrong under his father’s name, as I guess he thought Festurs was more distinctive than Frank William Pragnell. And he’d be right. Though weirdly, he went by it in real life also.

Working name of Frank William Pragnell (1905-1977), UK police constable, clerk and author who was known all his life by his father’s first name, Festus (even in the 1911 census, his wedding banns and his own will: “Frank William, known as Festus”).

So, you know, science fiction writers have always been weird, one way or another.

Anyway, the fact that he was from the UK is germane for the very weird things he does to the character, who is of course — for coolness (I thought it was mandatory when I was young, to be fair) an American — and they’re the sort of weird things someone from Britain who didn’t know a heck of a lot about America would do. For instance, his character’s name is Learoy Spofforth and he goes by Lea. This doesn’t seem to be an attempt to mock the character, just what he thought was a good, convincing American name.

Now, I will grant you all I know about the America of the thirties is from reading biographies, but even so that struck me as a fairly bizarre name to give anyone. Add to it that this man’s profession, and the reason he’s “well known in America” is that he’s a “lawn tennis champion” and I’ll give you a minute to roll on the floor laughing or at least scratch your head and wonder how big tennis was in the America in the thirties. And again, I’m right there, scratching my head along with you, but in all the books written in America at that time, I hear them talking about baseball, occasionally football, but mostly baseball. I don’t know if there was enough of a golf fandom. But I can honestly say never have I heard of tennis as a sport that fascinated people or made someone nation-famous. Eh. Perhaps he just assigned this guy the first sport he could think of.

Anyway, the book opens with a bang. Poor Lea is waiting trial for having bashed his brother, Charles’, head in.

He tells us he’s 28 but lived 80 years. And then he talks about his brother being a scientist and discovering worlds in atoms. From there we go to his brother saying he’s found life in one of these worlds, human like life. And his machine should be able to send a mind into the mind of one of the humans in the atom.

After various alarums and excursions poor Lea finds himself in the head of a green man. Now if you’re thinking green men after a lifetime of the culture talking of little green men. This green man is not little but a sort of massive green primitive ape, living in a green primitive culture that has caves lit by electricity speaking either of a greater culture or a decayed one.

The green ape, Kastrove, is in the middle of a raid to capture a woman who has landed in a flying machine, and who has yellow hair and looks fairly elfin. The minute Kastrove, or Lea perhaps, sees her he’s taken with a great desire to have her.

He does in fact capture her, which leads to various things including fights in his tribe, but he takes her for a mate and keeps her.

Now, since we know we’re going to be going through sixty two years, I hope you don’t expect a carefully introspective romantic relationship. We are in fact told that she comes to love him because he’s so kind to her, and they have a baby who looks — he tells us — as a normal human.

She comes from an elfin culture that lives in the ruins of an ancient, decayed civilization and no longer knows how to use any of it.

When a supervisor/agent of the larbies — the overlords over both apes and her people — comes to greypec, Kastrove’s village, for reasons of primitive politics, he takes Kastrove and Issa his mate with them to be trained as soldiers. They also take Kastrove’s and Issa’s son to train as a village leader as he grows. That’s the last we hear of them.

Throughout there are mentions of Gorlems, the enemy.

The training of Kastrove makes it obvious most of what’s happening is the Larbies mind controlling the apes and the elfin creature by hypnosis and mind control.

After several adventures, Kastrove helps a Gorlem prisoner (they’re sort of a wizened humanoid) escape.a The escapee dies in the escape, but Kastrove ends up working with the Gorlems to help them win the war against the Larbies.

The Larbies btw are intelligent molluscs and utterly ruthless.

Kastrove’s mind — Lea’s — retains all the science subconsciously, and when the Gorlems extract it, it allows them to win.

Anyway, Kastrove gets Issa back and they have a passel of kids, and then he gets back to his own time and world. I can’t say that is a spoiler, since of course the book starts with him back in Britain.

I won’t tell you the resolution which at any rate I really didn’t like as it falls under “strange psychobabble nonsense.”

So, it’s less outdated than the Adrift in the Stratosphere book. I wonder if I did read it as a kid, because I remember thinking of the atoms having worlds, and of a universe being born every time I struck a match, then dying when I blew it out. But of course there have been other book with those ideas. Curiously, his view of the atom is more current than what I was taught in middle school, but never mind that.

Most of the science fiction in the book is… well, space opera intensive. The guns fire both pellets and green gas; the cars are interesting and of different kinds; there are ruins of a greater civilization; the Grolems are what you’d expect of an “advanced civilization” as seen in the 30s.

There is the bit about how their civilization got in this trouble, because they didn’t have socialism and racial hygiene, but those were just the ideas in the air at that time.

One of the more curious ideas I found that strikes me as a distortion of the concept of evolution was his belief that given time all animals in a world would evolve sentience and intelligence to some degree.

Another point that amused me is that I might have found the “Women don’t do anything” book that allt he feminists go on about. And even here it’s not true. Yes, Issa serves as a prize of sorts in a bunch of sections of the book, but she also gets trained as and serves as a soldier (even if indoctrinated) and she chooses Kastrove, in the most unlikely romance.

The advice given about women is so quaint it’s almost hilarious. We get a bit of funny early 20th century advice from Kastrove’s father who says you shouldn’t count on getting good at relationships until your fourth. And then the end punch is kind of highly complimentary and silly about how women work.

Meanwhile really I do understand why this would upset feminists nowadays. Because most of the action is in a man’s world, so to put it, with women as accessories of sorts. But part of this reflected the world the author lived in. I figure police work at that time was mostly a male thing, with some women but not enough to impinge too much on the consciousness. Even married men lived in more separate spheres from women than men today. This is something we underestimate now, how sex differentiated society was back then.

And they were writing for men, mostly. Not that women didn’t read, but then (as frankly now, except for some side sub-genres) they didn’t read much science fiction. So to an extent it was written and read by men who lived in very male spheres.

They had women in as prizes, as unattainable goddesses, and when they were in they were often brave and valorous. But they were peripheral to the main action.

However to not see the difference between that and the current fiction, which is almost obsessively female centered and keep harping for more and more is sort of like winning lottery and keeping whining that you need more money for a cup of coffee.

The story itself is a rollicking adventure of the sort you might find in any pulp magazine, not deep thought and not pretty words, but entertaining nonetheless. And again, he must have done something right as there were at least four foreign language translations that are easily found, and he’s still read today.

To the extent it is unsatisfying is that it reads, to modern eyes, almost like an outline. There is no exploration of anything, including the setting (actually characters are relatively well fleshed compared to the settings) or the various social pressures. I mean, things are there, but they come at you at such breakneck speed that things kind of fall off, and often you find out what is happening as you’re in the middle of it, and not in a good way. Like you find out they were starving not while they’re looking for food, but after they find it.

I think this is more than anything the result of movies and TV being all prevalent. At the time it was enough — more than enough — to have a movie in your head and for it to move fast and be really interesting.

Nowadays books are a different experience from movies, and we expect more emotion, even if the emotion is suspense and fear in action sequences.

Yet and again, though it might not set the twenty first century apart, Festus Pregnell’s Green Man of Greypec is an eminently enjoyable, or enjoyable enough book. I still read it without getting a need to throw it across the room, and it is still being talked about.

May I be so lucky.