First of all, let’s not accept the current definition of “literature.”

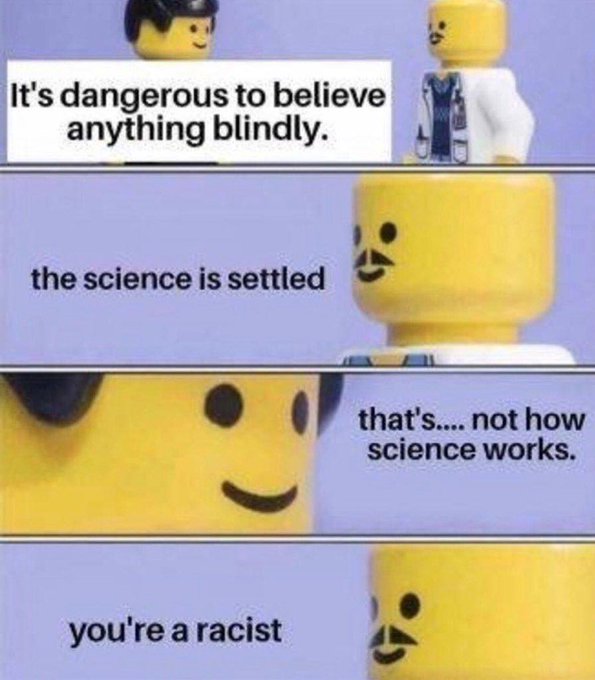

Mostly because it makes no sense. If you dig into “literature” as opposed to “genre” what you get is two non-falsifiable statements: “Literature is bigger/deeper/more important than genre.” and “Literature is what literature professors anoint as literature.”

In both cases, if you try to pursue it, you are met with stompy feet and “because we said so.” Now it’s stompy feet and “because we said so” dressed in a lot of verbiage that means “stompy feet and because we said so.”

Look, not only do I have a degree in literature, and read up a lot of literary criticism (look, it was that or read the miserable books their assigned us.) but I also read a lot of how to write books, a lot of whom are written by precious, precious literary fiction authors and professors, who at some point in the book — often after sharing really good craft tips — go psychotic and start screaming about “genre trash” and how they don’t write that.

One of them, which I finally threw away — one of three books I actually threw away instead of giving away or selling — ten years later, when I couldn’t get over my anger enough to continue reading the book, went on wonderfully till the middle of the book. I can’t remember the title, because I do this to books that really p*ss me off, but it was something like “by hook or crook”. It was about how to write immediate fiction and hook the reader. To the middle of the book, it was really excellent. Stuff like not using “he thought” but just giving us the character’s thoughts, or showing emotion through actions rather than telling us he was happy or sad.

And then in the middle of the book, out of nowhere, the author goes on a snit about how if you aim to write genre this book is not for you, because you don’t need his instruction to write that simplistic, formulaic, etc. etc. etc. “trash.”

Other than reaching through the pages of the book and grabbing the author by the throat and giving him a reading list, there was nothing I could do with my angry. I knew for a fact, however, that he was running on what he’d been told genre was, or perhaps on two or three very OLD and bad novels.

Look, I have a sort of proof of this. In my long careen through college, I kept meeting professors and teachers who would say this. I would approach them after class, very politely, and ask them if I could change their minds. I was even willing to LOAN them the books, etc. After pouting, screaming, or sneering, most of them agreed. (I was young, cute, and very very polite.) I will admit I tailored my point of attack to each professor by their weaknesses. I have yet to meet someone with a poetic bend who won’t fall headlong for bradbury, or someone of a philosophical bend who won’t fall for Phillip K. Dick. Anyway, in every case, regardless of how resistant they were to begin with, I got a science fiction (or mystery. I didn’t read romance till my mid thirties. As in not a single one. Shut up. Sit down. that’s another post called “What women read and write.”) book on the curriculum if not that year the year after. They were in fact sneering at genre fiction that existed only in their heads.

Recently I came across someone sneering that if you need a plot you’re obviously not a grown up, and how literary fiction is “life” — by which they mean “slice of life.” Except of course, this excludes Shakespeare, Dickens, Jane Austen and practically everyone before the 20th century, so again, I think we’re dealing with weaponized ignorance.

Everything fell into place when I realized as a professional writer that “literary fiction” was a genre, with genre rules. The rules, other than some newly created to distinguish them from “genre trash” could be summarized as “reading this makes me sound like an educated person.” (This is interesting, so put a pin in it.) That’s fine, except for its devotes insisting it’s the only valid and important one, and the only one that should be taught.

In the late twentieth century “makes me sound like an educated person” given what higher education had become usually meant “is either Marxist at its inception or is possible to interpret adequately through a Marxist lens.” No, that’s not what it was described as, but it was what it was. I spent countless hours talking about the power relationship between two characters, or how it illuminated the plight of blah blah blah. (Look I can spin the babble on command, but I just ate, and I don’t want to get queasy.)

What it used to be until um…. WWI was “has markers that the writer has read and studied classical myth and other foundational works of Western civilization.”

Both of those amount to “Shows the writer — and by extension the reader — had an expensive education.”

Why it switched between classical culture and Marxism has a lot to do with WWI and disenchantment with Western tradition as well as a particularly active and successful communist agit prop. And the fact that, as a just so story with its own language and easy to superimpose on reality — and more so on literature — theories and power dynamics, Marxism is like catnip for academics.

Ignoring that later part and the utter weirdness of post-modernist-literature, that mostly aims at hysterically claim superiority because they read books without plot, or dialogue, or characters, or whatever the heck the newest innovation is (I actually was forced to read a novel where the novelist had removed the element of “time.” It was acclaimed as super-innovative, but it was two people having a never ending discussion in a car. Sophomore drunken babble as literature. That was a thing. (Drinking helped with reading it too.)) because that’s just posturing with pages, let’s look at the function literature provided before.

Let’s say that whatever “literature” is for, it has nothing to do with ludic reading, and it’s not designed to get you to read for fun. I propose that they should be completely separate classes. English or Language Arts or whatever they call it these days should stick to its knitting and concentrate on literacy 101. Provide a variety of books. Ask people to read and write about the ones they actually enjoyed and help students become familiar enough with reading to read for pleasure. In elementary school this might include providing boys with comics, because being more visual boys tend to love comics. (And let me enjoin mothers of little boys to seek out Don Rosa’s Disney comics. They’re perfect for that awkward stage where the kids need more story than their reading ability allows them to enjoy. Let them free on those, and I guarantee they move on to real reading. (Defined as reading for all purposes one uses reading, from information to pleasure.)) But at this stage, really, except for keeping age-inappropriate stuff (like detailed descriptions of sexual acts out of the hands of pre-pubescent children) teaching reading should be the offering of a smorgasbord, and the teacher should be more of a concierge, with a deep knowledge of what’s available, and the ability to guide the kid to what will work for him or her. (As well as teaching grammar, proper sentence construction, clarity in writing, and the like.)

At around eleven or twelve, a new class should be introduced. I have absolutely no idea what to call it. Calling it Study of Literature confuses it with the “Literary” genre, and in point of fact there is very little — if any — overlap.

The purpose of this class would be the reason to “teach literature”.

Allow me a digression: I didn’t realize I had eidetic or near eidetic memory until I had a head injury that robbed me of it. The reason I didn’t realize it is because I knew what eidetic meant. My brother was eidetic. He could, effortlessly, tell you what had happened on any given day, who had won soccer games on a given weekend three years ago, etc.

What I missed: You don’t remember what you never paid any attention to, and being ADD AF and liable to get distracted by internal story telling, I never heard/paid attention to most of life.

Anyway, I should have realized I was eidetic, because from the moment I started tearing through the family library (by which I mean accumulation of books. They weren’t in any particular room, but everywhere and also in crates in every storage space in the family houses) my brother and I talked entirely in literary allusions.

By which I mean, we could sit at the table and one of us would quote the three musketeers, to which the other would answer with a line from Hercule Poirot, at which point the other would quote the Bible in response.

It all made perfect sense to us, because we had a vast fund of reading the same books, which only got deeper and vaster as we both dropped into science fiction at the same time.

It was however utterly and completely opaque to everyone else. I think my dad caught most of it, except the science fiction, but mom who doesn’t read fiction was completely baffled and annoyed by it. (Which made it more fun. I mean, we were her kids.)

I remember being confused as to why my parents got very embarrassed by our bringing out our act at big family parties or when we had guests. You see, having grown up like that, it never OCCURRED TO ME that other people didn’t understand it. They were adults, so of course they’d read (and memorized, duh) all of it, right?

It wasn’t till I was in high school and made significant friendships outside the house that I realized not everyone read the same things, and most people didn’t memorize every word they read.

Let’s say part of what predisposed me to marry Dan is that despite not having read the exact same things, he’d read things similar enough to catch the allusions and surf through my various references without losing the thread.

Now, that is the reason to teach literature at all, as opposed to “reading” which is not the same thing.

“What?” You say. “So kids can baffle adults at table?”

Um…. No. To provide people with a cultural vocabulary of allusion and situation and character that they can refer to, one that everyone else understands.

To a great extent that has been lost in our society, except for movies or for … um… subgroups within the society. Geeks have their vocabulary and cultural touchstones. Romance and rom com affictionados have theirs. Adventure or thriller movie fans have their own.

That’s fine. I’m not an anti-genre or even anti-other-forms-of-storytelling fanatic. I’m an “And that too” type of person.

However, there is a thing we’re missing, and it keeps coming back to bite us in the ass: A common cultural background, a common referencial archive, a commonality of archetypes that we can access AS A CULTURE and speak from as a culture.

We’re missing our TRIBAL lays, as it were.

Movies that were really big across every portion of society in the past provided a bit of that, say “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” has a force brought on by the scene in the movie. For that matter so does “come to the dark side.” But as audiences and movie interests have become more fragmented, both by interest and generationally, it stops working. (Watch people lamenting that no one gets “Was it over when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor?” or other touchstones of previous generations.)

This is where there is a place to study literature — and I suppose at this point, some of the older movies. Like, yes, Gone With The Wind. — because most of the founding stones of our culture were written. (Or declaimed, if you go back long enough.)

Start with Greek Myth. At the very least the Odyssey and the Iliad. In this diminished time, it is allowable to do it in translation, though at the very least Latin should be encouraged. Greek if people have a bend to– Okay fine. Vulgus language, in our case English will do. But I want you to know I’m stompy footing and rolling my eyes, even though I have little Latin and small Greek.

Yes, sure, you can sanitize it for kids under 12. If you must. Though I’m here to tell you that the castration of Saturn did not particularly shock me at 10, because these were obviously not humans.

Sure, you can throw Norse myth in, if you absolutely feel like it, but I’ll point out that if we’re sticking to the “foundations of the West,” that’s not a thing. That’s Johnny came lately and falls under “Oh, Timmy enjoys mythology. Let’s hit him with Norse myth and maybe Egyptian too.”

After that, I’m sorry, but yes, we need the Bible. No, this is in no way establishment of religion, first because I’m not proposing analyzing it from a religious POV (one can say “well, for that, you might want to talk to your parents/minister about that if the kid wants to discuss that part) but as literature, as “how does this story work, and how has it influenced every other story in the West?” And because I don’t propose reading it cover to cover. Genesis, sure. Some of the other more salient stories, including the parables of the New Testament, which are delightfully evocative. (No? Go re-read the Prodigal son.) And a discussion can be had on how attitudes changed over time/etc. Yes, it will offend some parents, but if one keeps drawing the line at “these are the foundational stories of the west” you’ll be fine. It can (and should) be done. Oh, and I’m intransigent in this, the Bible that should be taught is the King James Bible. Why? Because this is literature, and it has the best language.

The Bible will then prepare us for the chansons de geste of which some should at least be introduced, since the invention of romantic love is kind of important. From there, we should go into Shakespeare with both feet. (And recordings of the plays, yes.)

Then the field is more open. I absolutely think one should teach Dumas, because it opens the possibility of discussing the aristocratic society as portrayed, the picaresque form of novel, etc. I’m agnostic on Don Quixote.

A lot of things open from there, including, yes, possibly Jane Austen and yes, unfortunately likely the Brontes. (Sorry. I don’t actually enjoy the Brontes.)

All of it in context and in its own time. Yes, yes, Americans as a unique sub-group of the Western experience SHOULD study Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn and LIKELY Little House on the Prairie.

Before that and as the opening salvo to “We are Americans, begorrah,” we should study the declaration of independence, because that Jefferson fellow sure wrote purty but also because it will help understand Twain and Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Note this is in no way an exhaustive list, and I would leave it open to have other classes, catering to the kids… and er… young adults interests. It should be possible for someone to lose himself utterly in, oh, the writing of the quarttrocento or “south American poetry of the nineteenth century.” That would fall under “the common language culture of this or that interest group,” and might culminate, if you’re me, in a group of one.

But this much would give us a common reference, a common series of touchstones from which we could branch out. The idea is NOT to flaunt your excellent education, but to have something in common with everyone who grew up in this country and is older than x.

It gives you the national set of archetypes; allows for the assimilation of those whose parents were born abroad, and whose religion is more outre so they don’t sit in the pews every Sunday hearing certain stories, and create a foundation for “this is the thing we all know.”

Before anyone screams at me, I don’t object to the teaching of other passages from other holy books, mythologies, national tales, etc. Those are cool. But they shouldn’t be in the required core.

And nothing, absolutely nothing younger than 100 years should be in it, simply because it’s not been digested through the culture, and we don’t know what to take or leave.

None of these books should be presented as “we read this because it’s how all books should be” but as “these are things people repeated, and read, and based things on for centuries. They’re sort of in the DNA of our culture, and are referenced in later story telling. Knowing them will make it easier for you to communicate.” (Yes, I would absolutely throw Uncle Remus in the basics, somewhere before Mark Twain. And yes, I realize I hesitate to put it in because people will scream. But both as historical context and reference, it’s now part of our culture. (Don’t throw me in that briar patch.) Also it’s part of my personal tradition, as a translation of the stories was one of the very first books I read by myself. So racissss, etc. Bite me.)

The truth is that we’re teaching literature all wrong, teaching it as an aspirational “this is how you should write, and this is what is appropriate to read.” What we should teach it as is “This is the common foundation of our culture. Yes, some of it will read super-boring to you because of out-dated language or because you lack the mental furniture. But his is how you acquire a familiarity with the language and appropriate it as your mental furniture.” And “This is why this particular work is important to have read, and this is the context in which it became widely read.” Oh and “this is how people of the time saw it, and why they liked it.”

(Why, yes, I’d love to start a series of videos teaching just this stuff, that way, and it might yet happen, if the health stabilizes. It could happen. I know, I know what it looks like from the outside, but from the inside, despite sudden collapses, it’s improving.)

I still have no idea what it would be called.

But it would forever end the literary/genre wars and the bizarre idea there’s a divide. Genre that survives long enough becomes literature, and in my lifetime, if I live another 10 years, Agatha Christie will be “literature” if she’s not already. (And there is a reason to study her and other mystery writers (and some science fiction) under a cultural history of the 20th century. There are … fossilized opinions and situations that are better at explaining how people thought and felt than any theorizing of historians. But that’s not “literature.”)

And that’s how and why I think “literature” should be taught. Perhaps “foundational documents” would be a better name for it. Or … Tribal Lays. (Imagine what fun teen boys would have with THAT!)

Anyway, this is my opinion and how I’d change the teaching of stories, if I ruled the world. Oh, and my list is in no way exhaustive and I’m not married to it, except for the Greek Myth and the Bible. And the declaration of independence.