Born Free

There’s men, there’s women, there’s writers.

Sure, writers, in general, are women or men, but honestly, if we were free floating brains in jello it would make more sense. What I’m trying to tell you, ladies, germs and small octagonal coasters is that no, you can’t make broad sweeping statements like “women write” or “men write” X, Y or Z. Much less “women read” and “men read” X, Y or most definitely Z.

Oh, you can make broad statements about how female brains work, how male brains work. What you can’t do is extrapolate it to “I don’t read women, because they all write fairy princess unicorn sex with hot monsters.”

Or actually, no. You can absolutely extrapolate that. Because you have the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and if it makes you happy to be an arrant idiot, who am to stop you?

Why yes, indeedy, I’ve woken up and chosen violence. If it makes you feel better I’m not writing this in the morning, but late at night on Thursday, so I’m actually falling asleep and chose violence. There. That’s better.

Look, there are certain tendencies in male and female writing, proceeding from our brains being different. This allows to say, broadly, men prefer things and how things work. Women prefer people and people’s relationships.

If you’re working with a broad enough group, you can — therefore — predict that more men will write techno-thrillers where how the McGuffin works is super important; more women will write romances.

This btw has absolutely zero to do with whether either book will have more sex. That depends more on trends in publishing, what the public expects and — if going trad pub — what the publisher demands. Sex is a different thing. Yeah, we can get into sex (the gentleman who giggled in the back row can sit outside with no books for ten minutes) later, but let’s say that saying “This book has tons of sex, therefore it’s for girls” is a non starter.

For years most romances were what we now call “sweet romances” and arguably they sold better than today’s “must have a sex scene four times during the book. Some of the best selling romance writers use the same scene every book, which I found out while I was reading romance (more on that later) and just change the color of the hair, dress, and what the girl tripped for to fit the circumstances, because they don’t care for that part, but the publisher wants it in. Don’t tell me that their readers are passionately interested in those scenes, or they’d protest more.

Anyway, you can generally say “if it’s a people oriented story, it’s more likely written by a woman” “if it’s a “how things work and consequences of how thing works” it’s probably written by a man.” And you’ll be right… Oh, 70% of the time, give or take two or three percent.

I pulled that figure out of the air, but it’s my “feel” from reading a lot.

Now this is somewhat skewed because you don’t actually know the sex of the writer, just what they put on the book spine, and writers are thoroughly unreliable for telling the truth. I mean, we make money from lying. I have it on good authority — know some of them — that some bestselling romance authors, with female names, are actually male. And there are thriller authors out there who use initials or well… just the closest male name.

The really cool thing, particularly if you’re an indie, is that you can be a dog just typing as fast as you can, on the internet no one knows.

Oh, I said romance because that’s the extreme, but cozy mysteries tend to have female names, versus thrillers, which actually tend towards initials.

“But Sarah,” You’ll say. “You can’t deny more women read romance and more men read mil sf or thrillers.”

Okay, you got me there. By self declared preference, I can’t deny that. I can’t deny it because two people I am closely related to and who are not only male but techy and very, very male-brain will be deeply upset if I reveal they like the goopiest romances and the floofiest of floofy cozies, to the point they’ll be talking about these books, and I’m going “You’re just making that up!”

Me? Well, me as a reader started out reading-like-a-boy mostly because I inherited all the books from my dad, brother and cousins, so of course I read “male.” However, note that they interested me more than the romances (blue cover collection. No, seriously) my female cousin had. I did however like A Little Princess, which my brother hated, and I enjoyed Enid Blyton’s boarding school books, which are very feminine, just as much as I enjoyed the adventure ones which yes, pretty much baffled my male family members.

I didn’t however read even Jane Austen till my early twenties, and no other romances till my mid thirties, and then at the behest of a male friend.

I prefer science fiction to fantasy (no, not hard science fiction, but that’s a discussion for later) and my fantasy tends to suffer from science fiction brain, in that I can’t just have “and suddenly everyone had magical powers” but I have to invent a mechanism for them and thread them backwards through history in a way that works. otherwise I don’t believe in them, and when I don’t believe in stuff it doesn’t get written.

(Understand the science fiction referenced here is a quality of the mind, and the quality is “okay, it might take a miracle to have anti-gravity, but if we had anti-gravity it would work via machines and in a way that was understood to someone who created it, not wished out of the blue by magic and therefore unreliable.” Yes, I know there are logic errors. You also know D*MN well the “feel” I’m talking about. I know science fiction when I nail it to the keyboard.)

By the time I read my first “romance, romance” I’d read hundreds of military biographies and military fiction, ranging from historical fiction to science fiction. (I can’t write it. No. The problem is not actually the battles, and I don’t flinch from action. No, my problem is the ranks and the mil-speak. It’s like another language, and I don’t absorb it from reading for some reason. To be fair, I also suck at learning dialects from reading. I can understand them fine, I just can’t write them.

Anyway, I even understand those of you who don’t want to read books with female names on the cover. It’s stupid, but it’s a stupidity I’ve engaged in myself. “If there’s a female name on the cover, there’s going to be stupid feminism inside.”

Now, it actually depends. Most Jane Austen fanfic, for instance, has female names on the cover (no, not all. Two of my favorite authors are male, and one, according to his bio is a marine. You can tell too. Why? Because every military man in the story, no matter how peripheral in the original is a boss and a hero in the story. They’re also all buff and super-sexy. Sigh. No projection going on there. BUT the guy writes characters WELL, and the stories hang together.) and the ratio of decent to suddenly suckerpunches me with OMG what Critical Race Theory or Feminist cant is about 7/3. Though I grant you only ONE male has sucker punched me that way. However he suckerpunched me very very hard, with vast amounts of 21st century psychobabble poured into the middle of a regency. Also considering there’s maybe 5 men I remember seeing, as opposed to 50 or so women, the fact one of those men is a leftist loon means we’re about even.

However science fiction with a female name on the cover? Six times out of ten — if not indie — it’s some woman creating the wonderful, beautiful female society in which all men are virtual slaves and not even sex slaves. Far more likely of course from recent and trad pub.

However men also have a high incidence of crazy in SF. Even fairly sane men will tell me that half of Europe is under water 200 years in the future because climate change.

Mystery in general trends more left than Science Fiction in my opinion because mystery lacked the equivalent of Baen, before indie became a thing.

Anyway, it’s like this, I was chased from science fiction, where I could only find lefty lectures, to mystery, where there were still mostly lefty lectures, to romance, where the older ones were okay, but increasingly, even in Regencies every woman was a suffragette and running a shelter for abused women, to history and biography where… the recent ones also couldn’t be trusted and became increasingly worse.

Then we got indie, and while I still get bitten sometimes, it’s a matter of evaluating, and remembering the names of authors who pissed me off (it’s a problem, as I usually only remember authors I love.)

Have I found differences between male and female? Well, no, not really. Sure, some people write in an excessively feminine way and are actually female. And some men are purveyors of zap zing bang fights and are male. (Some of the males also give me eye-glazing descriptions of the internal mechanisms of machines that never existed. Okay, guys, I know there’s such a thing as selling it as real, but there are also limits.)

I don’t write hard sf not because I’m female, but because right now, at this particular time in my life (this might change) I don’t have the ability/time to do copious amounts of research, and anyway, the stories I want to tell RIGHT NOW can’t fit into hard sf.

This might, and probably will change, once I get through the current batch of work that has been waiting, some of it over 40 years.

I don’t need to tell you there’s a ton of guys that write space opera and soft/adventure SF right?

In the same way, right now, I don’t write “red hot” romance or erotica. Will this change? I want to say probably no, given the things on the docket, but I’ve learned not to taunt the happy/fun muse.

On “But women just write sex with weird fantasy characters,” I want to make a point of order. An important one: I think women do that to escape the imperatives of feminism. Younger women don’t want to openly rebel (that’s another of those brain things. Most women are more group-oriented. Note “most”. Some of us were born with middle fingers aloft) but also don’t want to think about whether they’re as feminist as they should be, etc. Hence, fantasy monster romance, both for writing and reading. (No, I actually don’t get it. Not taunting the happy fun muse. Just confused. No interest in writing this. (The lady who just shouted an idea can wait outside the door for ten minutes, with no books.))

Almost every writing couple — there are a lot of them — I know, they both say all the goopey, romantic, sentimental scenes are the guy’s responsibility.

I believe that. In my 50/50 collab with a male, most of those sentimental “so many feelings” series I get accuse of having written (because vagina) the guy wrote. He will tell you that too.

And that’s the other thing “Women just write about feelings!” While it’s bad to write ABOUT feelings — ideally I should make you FEEL the feelings — this is another thing where you can shout it and stomp feet all you want to. BUT in the end story telling is meant to evoke feelings. If it doesn’t arouse your feelings — not those feelings. Outside the door. No books. Ten minutes — why are you reading it, instead of reading a technical manual? In fact, making you feel the feels and be in the character’s head is what written fiction has that is better than movies.

And guys, at the end of The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress? When Mike doesn’t answer? I cry. No matter how many times I read it. And yeah, RAH was a man.

Sex — I told you I’d get there — there is a a lot more of it in books today, across the board, than in the past. All genres, all sub genres, from writers of either sex or or, you know, both sexes together.

I’m not sure that’s revealed preference of writers or readers. It’s simply because trad pub gyrated to it in a last scramble to sell. Because sex sells. (Less and less every time, but whatevs.) So, therefore, we got used to more sex in every book.

Does it help the book sell? I don’t know. I suspect some books need it as they have very little else. But every book? I doubt it.

Look, not only can people read/access porn in a million other ways, but for males at least — brain wiring thing — pictures are way better than words on a page. For women… it’s complicated. The words on a page work, but they usually want the emotions too.

I’m not anyone’s mother or morality police. But I do tend to get tired of sex that does nothing to advance the plot. I think a lot of indie authors suffer from a belief they’re living in the 1940s and that if they make the book spicy it will stand out. In fact, everyone is making the book spicy and it neither shocks, surprises nor tantalizes practically anyone.

In summation: you can be sure women just write this stuff you surely don’t like. But in fact all you know is that some people with female names on the cover write that, and others don’t.

I’m not your mother. I’m not your teacher. You’re allowed to say whatever stupid things you wish, even if they’re provably false. It’s a great country, isn’t it?

I have no problems with anyone not liking my writing. This is a thing. I’ve bounced off the writing of excellent authors that I know are excellent because people I trust love them. Writing is like dating. I could be a supermodel, but not everyone is going to want to date me.

I do have a problem with people not even trying me, even when they know my politics because “Every woman does x, y, z”. (Oh, and a word to the wise, if you’ve read one of my series, you’ve read that series. There is no earthly resemblance between say, the Shakespeare fantasies and Daring finds cozy mysteries. or Darkship Thieves. Look, I just read and write a lot of different styles, okay?)

I don’t expect to change the minds of anyone who thinks that way, no. If you think that way, it’s your right. But I reserve the right to vent.

Which is what this post has been.

And now I’m almost wholly asleep, and I’m going to bed, violence having been done.

First of all, let’s not accept the current definition of “literature.”

Mostly because it makes no sense. If you dig into “literature” as opposed to “genre” what you get is two non-falsifiable statements: “Literature is bigger/deeper/more important than genre.” and “Literature is what literature professors anoint as literature.”

In both cases, if you try to pursue it, you are met with stompy feet and “because we said so.” Now it’s stompy feet and “because we said so” dressed in a lot of verbiage that means “stompy feet and because we said so.”

Look, not only do I have a degree in literature, and read up a lot of literary criticism (look, it was that or read the miserable books their assigned us.) but I also read a lot of how to write books, a lot of whom are written by precious, precious literary fiction authors and professors, who at some point in the book — often after sharing really good craft tips — go psychotic and start screaming about “genre trash” and how they don’t write that.

One of them, which I finally threw away — one of three books I actually threw away instead of giving away or selling — ten years later, when I couldn’t get over my anger enough to continue reading the book, went on wonderfully till the middle of the book. I can’t remember the title, because I do this to books that really p*ss me off, but it was something like “by hook or crook”. It was about how to write immediate fiction and hook the reader. To the middle of the book, it was really excellent. Stuff like not using “he thought” but just giving us the character’s thoughts, or showing emotion through actions rather than telling us he was happy or sad.

And then in the middle of the book, out of nowhere, the author goes on a snit about how if you aim to write genre this book is not for you, because you don’t need his instruction to write that simplistic, formulaic, etc. etc. etc. “trash.”

Other than reaching through the pages of the book and grabbing the author by the throat and giving him a reading list, there was nothing I could do with my angry. I knew for a fact, however, that he was running on what he’d been told genre was, or perhaps on two or three very OLD and bad novels.

Look, I have a sort of proof of this. In my long careen through college, I kept meeting professors and teachers who would say this. I would approach them after class, very politely, and ask them if I could change their minds. I was even willing to LOAN them the books, etc. After pouting, screaming, or sneering, most of them agreed. (I was young, cute, and very very polite.) I will admit I tailored my point of attack to each professor by their weaknesses. I have yet to meet someone with a poetic bend who won’t fall headlong for bradbury, or someone of a philosophical bend who won’t fall for Phillip K. Dick. Anyway, in every case, regardless of how resistant they were to begin with, I got a science fiction (or mystery. I didn’t read romance till my mid thirties. As in not a single one. Shut up. Sit down. that’s another post called “What women read and write.”) book on the curriculum if not that year the year after. They were in fact sneering at genre fiction that existed only in their heads.

Recently I came across someone sneering that if you need a plot you’re obviously not a grown up, and how literary fiction is “life” — by which they mean “slice of life.” Except of course, this excludes Shakespeare, Dickens, Jane Austen and practically everyone before the 20th century, so again, I think we’re dealing with weaponized ignorance.

Everything fell into place when I realized as a professional writer that “literary fiction” was a genre, with genre rules. The rules, other than some newly created to distinguish them from “genre trash” could be summarized as “reading this makes me sound like an educated person.” (This is interesting, so put a pin in it.) That’s fine, except for its devotes insisting it’s the only valid and important one, and the only one that should be taught.

In the late twentieth century “makes me sound like an educated person” given what higher education had become usually meant “is either Marxist at its inception or is possible to interpret adequately through a Marxist lens.” No, that’s not what it was described as, but it was what it was. I spent countless hours talking about the power relationship between two characters, or how it illuminated the plight of blah blah blah. (Look I can spin the babble on command, but I just ate, and I don’t want to get queasy.)

What it used to be until um…. WWI was “has markers that the writer has read and studied classical myth and other foundational works of Western civilization.”

Both of those amount to “Shows the writer — and by extension the reader — had an expensive education.”

Why it switched between classical culture and Marxism has a lot to do with WWI and disenchantment with Western tradition as well as a particularly active and successful communist agit prop. And the fact that, as a just so story with its own language and easy to superimpose on reality — and more so on literature — theories and power dynamics, Marxism is like catnip for academics.

Ignoring that later part and the utter weirdness of post-modernist-literature, that mostly aims at hysterically claim superiority because they read books without plot, or dialogue, or characters, or whatever the heck the newest innovation is (I actually was forced to read a novel where the novelist had removed the element of “time.” It was acclaimed as super-innovative, but it was two people having a never ending discussion in a car. Sophomore drunken babble as literature. That was a thing. (Drinking helped with reading it too.)) because that’s just posturing with pages, let’s look at the function literature provided before.

Let’s say that whatever “literature” is for, it has nothing to do with ludic reading, and it’s not designed to get you to read for fun. I propose that they should be completely separate classes. English or Language Arts or whatever they call it these days should stick to its knitting and concentrate on literacy 101. Provide a variety of books. Ask people to read and write about the ones they actually enjoyed and help students become familiar enough with reading to read for pleasure. In elementary school this might include providing boys with comics, because being more visual boys tend to love comics. (And let me enjoin mothers of little boys to seek out Don Rosa’s Disney comics. They’re perfect for that awkward stage where the kids need more story than their reading ability allows them to enjoy. Let them free on those, and I guarantee they move on to real reading. (Defined as reading for all purposes one uses reading, from information to pleasure.)) But at this stage, really, except for keeping age-inappropriate stuff (like detailed descriptions of sexual acts out of the hands of pre-pubescent children) teaching reading should be the offering of a smorgasbord, and the teacher should be more of a concierge, with a deep knowledge of what’s available, and the ability to guide the kid to what will work for him or her. (As well as teaching grammar, proper sentence construction, clarity in writing, and the like.)

At around eleven or twelve, a new class should be introduced. I have absolutely no idea what to call it. Calling it Study of Literature confuses it with the “Literary” genre, and in point of fact there is very little — if any — overlap.

The purpose of this class would be the reason to “teach literature”.

Allow me a digression: I didn’t realize I had eidetic or near eidetic memory until I had a head injury that robbed me of it. The reason I didn’t realize it is because I knew what eidetic meant. My brother was eidetic. He could, effortlessly, tell you what had happened on any given day, who had won soccer games on a given weekend three years ago, etc.

What I missed: You don’t remember what you never paid any attention to, and being ADD AF and liable to get distracted by internal story telling, I never heard/paid attention to most of life.

Anyway, I should have realized I was eidetic, because from the moment I started tearing through the family library (by which I mean accumulation of books. They weren’t in any particular room, but everywhere and also in crates in every storage space in the family houses) my brother and I talked entirely in literary allusions.

By which I mean, we could sit at the table and one of us would quote the three musketeers, to which the other would answer with a line from Hercule Poirot, at which point the other would quote the Bible in response.

It all made perfect sense to us, because we had a vast fund of reading the same books, which only got deeper and vaster as we both dropped into science fiction at the same time.

It was however utterly and completely opaque to everyone else. I think my dad caught most of it, except the science fiction, but mom who doesn’t read fiction was completely baffled and annoyed by it. (Which made it more fun. I mean, we were her kids.)

I remember being confused as to why my parents got very embarrassed by our bringing out our act at big family parties or when we had guests. You see, having grown up like that, it never OCCURRED TO ME that other people didn’t understand it. They were adults, so of course they’d read (and memorized, duh) all of it, right?

It wasn’t till I was in high school and made significant friendships outside the house that I realized not everyone read the same things, and most people didn’t memorize every word they read.

Let’s say part of what predisposed me to marry Dan is that despite not having read the exact same things, he’d read things similar enough to catch the allusions and surf through my various references without losing the thread.

Now, that is the reason to teach literature at all, as opposed to “reading” which is not the same thing.

“What?” You say. “So kids can baffle adults at table?”

Um…. No. To provide people with a cultural vocabulary of allusion and situation and character that they can refer to, one that everyone else understands.

To a great extent that has been lost in our society, except for movies or for … um… subgroups within the society. Geeks have their vocabulary and cultural touchstones. Romance and rom com affictionados have theirs. Adventure or thriller movie fans have their own.

That’s fine. I’m not an anti-genre or even anti-other-forms-of-storytelling fanatic. I’m an “And that too” type of person.

However, there is a thing we’re missing, and it keeps coming back to bite us in the ass: A common cultural background, a common referencial archive, a commonality of archetypes that we can access AS A CULTURE and speak from as a culture.

We’re missing our TRIBAL lays, as it were.

Movies that were really big across every portion of society in the past provided a bit of that, say “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” has a force brought on by the scene in the movie. For that matter so does “come to the dark side.” But as audiences and movie interests have become more fragmented, both by interest and generationally, it stops working. (Watch people lamenting that no one gets “Was it over when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor?” or other touchstones of previous generations.)

This is where there is a place to study literature — and I suppose at this point, some of the older movies. Like, yes, Gone With The Wind. — because most of the founding stones of our culture were written. (Or declaimed, if you go back long enough.)

Start with Greek Myth. At the very least the Odyssey and the Iliad. In this diminished time, it is allowable to do it in translation, though at the very least Latin should be encouraged. Greek if people have a bend to– Okay fine. Vulgus language, in our case English will do. But I want you to know I’m stompy footing and rolling my eyes, even though I have little Latin and small Greek.

Yes, sure, you can sanitize it for kids under 12. If you must. Though I’m here to tell you that the castration of Saturn did not particularly shock me at 10, because these were obviously not humans.

Sure, you can throw Norse myth in, if you absolutely feel like it, but I’ll point out that if we’re sticking to the “foundations of the West,” that’s not a thing. That’s Johnny came lately and falls under “Oh, Timmy enjoys mythology. Let’s hit him with Norse myth and maybe Egyptian too.”

After that, I’m sorry, but yes, we need the Bible. No, this is in no way establishment of religion, first because I’m not proposing analyzing it from a religious POV (one can say “well, for that, you might want to talk to your parents/minister about that if the kid wants to discuss that part) but as literature, as “how does this story work, and how has it influenced every other story in the West?” And because I don’t propose reading it cover to cover. Genesis, sure. Some of the other more salient stories, including the parables of the New Testament, which are delightfully evocative. (No? Go re-read the Prodigal son.) And a discussion can be had on how attitudes changed over time/etc. Yes, it will offend some parents, but if one keeps drawing the line at “these are the foundational stories of the west” you’ll be fine. It can (and should) be done. Oh, and I’m intransigent in this, the Bible that should be taught is the King James Bible. Why? Because this is literature, and it has the best language.

The Bible will then prepare us for the chansons de geste of which some should at least be introduced, since the invention of romantic love is kind of important. From there, we should go into Shakespeare with both feet. (And recordings of the plays, yes.)

Then the field is more open. I absolutely think one should teach Dumas, because it opens the possibility of discussing the aristocratic society as portrayed, the picaresque form of novel, etc. I’m agnostic on Don Quixote.

A lot of things open from there, including, yes, possibly Jane Austen and yes, unfortunately likely the Brontes. (Sorry. I don’t actually enjoy the Brontes.)

All of it in context and in its own time. Yes, yes, Americans as a unique sub-group of the Western experience SHOULD study Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn and LIKELY Little House on the Prairie.

Before that and as the opening salvo to “We are Americans, begorrah,” we should study the declaration of independence, because that Jefferson fellow sure wrote purty but also because it will help understand Twain and Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Note this is in no way an exhaustive list, and I would leave it open to have other classes, catering to the kids… and er… young adults interests. It should be possible for someone to lose himself utterly in, oh, the writing of the quarttrocento or “south American poetry of the nineteenth century.” That would fall under “the common language culture of this or that interest group,” and might culminate, if you’re me, in a group of one.

But this much would give us a common reference, a common series of touchstones from which we could branch out. The idea is NOT to flaunt your excellent education, but to have something in common with everyone who grew up in this country and is older than x.

It gives you the national set of archetypes; allows for the assimilation of those whose parents were born abroad, and whose religion is more outre so they don’t sit in the pews every Sunday hearing certain stories, and create a foundation for “this is the thing we all know.”

Before anyone screams at me, I don’t object to the teaching of other passages from other holy books, mythologies, national tales, etc. Those are cool. But they shouldn’t be in the required core.

And nothing, absolutely nothing younger than 100 years should be in it, simply because it’s not been digested through the culture, and we don’t know what to take or leave.

None of these books should be presented as “we read this because it’s how all books should be” but as “these are things people repeated, and read, and based things on for centuries. They’re sort of in the DNA of our culture, and are referenced in later story telling. Knowing them will make it easier for you to communicate.” (Yes, I would absolutely throw Uncle Remus in the basics, somewhere before Mark Twain. And yes, I realize I hesitate to put it in because people will scream. But both as historical context and reference, it’s now part of our culture. (Don’t throw me in that briar patch.) Also it’s part of my personal tradition, as a translation of the stories was one of the very first books I read by myself. So racissss, etc. Bite me.)

The truth is that we’re teaching literature all wrong, teaching it as an aspirational “this is how you should write, and this is what is appropriate to read.” What we should teach it as is “This is the common foundation of our culture. Yes, some of it will read super-boring to you because of out-dated language or because you lack the mental furniture. But his is how you acquire a familiarity with the language and appropriate it as your mental furniture.” And “This is why this particular work is important to have read, and this is the context in which it became widely read.” Oh and “this is how people of the time saw it, and why they liked it.”

(Why, yes, I’d love to start a series of videos teaching just this stuff, that way, and it might yet happen, if the health stabilizes. It could happen. I know, I know what it looks like from the outside, but from the inside, despite sudden collapses, it’s improving.)

I still have no idea what it would be called.

But it would forever end the literary/genre wars and the bizarre idea there’s a divide. Genre that survives long enough becomes literature, and in my lifetime, if I live another 10 years, Agatha Christie will be “literature” if she’s not already. (And there is a reason to study her and other mystery writers (and some science fiction) under a cultural history of the 20th century. There are … fossilized opinions and situations that are better at explaining how people thought and felt than any theorizing of historians. But that’s not “literature.”)

And that’s how and why I think “literature” should be taught. Perhaps “foundational documents” would be a better name for it. Or … Tribal Lays. (Imagine what fun teen boys would have with THAT!)

Anyway, this is my opinion and how I’d change the teaching of stories, if I ruled the world. Oh, and my list is in no way exhaustive and I’m not married to it, except for the Greek Myth and the Bible. And the declaration of independence.

I actually have a follow up post to Charlie’s post yesterday, but it will wait till tomorrow, because by gum, Wednesdays are for fighting for a retrospective of my roots in science fiction.

Which since my essay for tomorrow is about why even suggest books for someone to read or do analysis and review at all, is one of the answers in advance: we can learn a lot of the history of a genre (or literature, or the time) from a few select books, in more or less chronological order.

I have to say this book was …. enlightening about the roots of the field. I’m sure I’ve read it before, but probably not among the first I read. The reason being that thought it was the first in collection argonauta I came on the scene considerably after it was first published and, to make things more complex, the Portuguese already had a version of printing to the net. Meaning they printed more or less what they expected to sell, had it out for a brief period, and that was it. I don’t know if they pulped the books that didn’t sell. I know by my time they continuously and egregiously underprinted, which is why when the “Greats” (look, Asimov, Heinlein and Simak, of course. What? I don’t know what to tell you. It was what it was) came out, there was a line outside the bookstore by the time it opened. Heck, there was a line outside the bookstore by 7 am. The bookstore opened at 9. By 10 the books would be gone. … by the time I was 16, I was the lone female and the only person under around 25 in that line. Also the only one who didn’t look like a caricature of an engineer. But I held my own, both in line and in the discussions. BTW, the guys were gallant. A couple of times when I’d arrived late and was far back in the line, people gave up the chance to buy the book so I could.

Anyway, this means that after that day, the book could only be found used; forgotten on a spinner rack in some smaller town (I scored glory road that way, with a faded front cover, in a beach resort); in the back of a closet in a box of others, (after you helped your friend’s family move and her father said, “Oh, yeah, I’d forgotten those books. I don’t think I’ll read them again. Do you want them?” And you call your dad to come pick you up because it’s too large a box to take in the train. Which is where I got Operation Chaos, and Simak’s City and Way Station.) Other ways. Trading with friends. And buying them from people willing to sell. And– I don’t think I ever did anyone’s homework for a copy of a science fiction book, but I did tutor people for books.

Anyway, as that implies, I read things in kind of a free form order. Books from the seventies, and books from the thirties, all mixed together.

Which is good, because I’m sure as heck not reading this in order, because of them aren’t “findable” and others some lunatic wants $500 for the paperback, so I’ll let it chill until someone issues it in ebook or in paper back again.

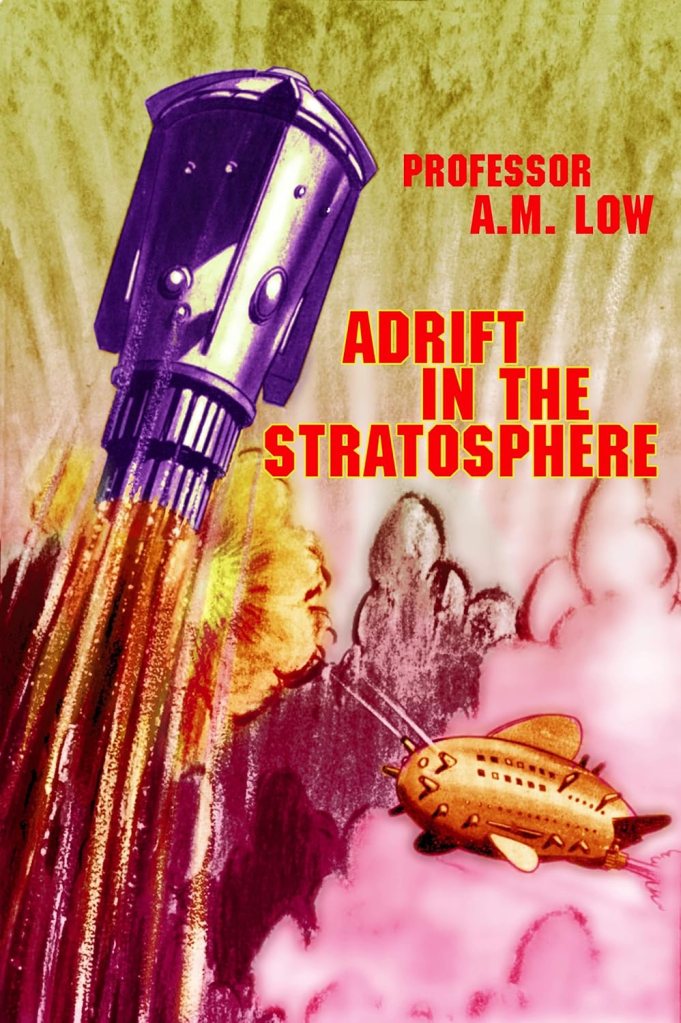

Anyway… ahem… this is not adrift in Sarah’s brain, it’s Adrift in the stratosphere, by A. M. Lowe, sometimes styled “Professor A. M. Low.” Was he a professor? Doesn’t seem so. He was also not a doctor, though some biographies indicate it. He was a notable engineer, but some people claim he never actually had any sort of degree.

If you’re terribly curious about the book, you can find it here: Adrift in the Stratosphere (Annotated).

And now you’re going to ask me if it’s worth it. Yes, in a way it is, though perhaps not for the same reason I’d buy a book written today.

There is a charming naivite to the book, a glimpse into a far less hidebound time. Which is not what you’d expect of a book first published in 1937. Look, we’re used to seeing them in their quaint clothes, and we know they had a lot more rigid society and– Yeah. Maybe. Maybe all of that. But I think while we loosened a lot of social interaction mores and manners, we added a whole lot of bureaucratic red tape and formalism and credentialism.

Anyway, the story wouldn’t be believable today and not just because we know there aren’t chunks of land, like islands in the stratosphere (though we do know that) but because none of us can conceive of three young men bicycling through the countryside and finding a spaceship in a barn, then accidentally launching themselves off. Whatever you think of the unlikelihood of what comes after (and it’s amazing how much we learned between 1937 and the moon flights) that beginning seems stupendously unlikely to me. Charming and alien, like something from a dream of childhood.

Perhaps that’s something we’ll recover, in the era of 3-d printing, and in an unimaginably more free and prosperous future, which is possible if not likely. Perhaps it will be possible, given future resources and the ability to look up all knowledge, who knows? That’s a lovely dream and one I’d like to see come to fruition. Not that I’ll live to see it, but the kids might.

Anyway, it starts with three friends cycling the country side. They stop and find a machine and accidentally end up on it.

I’ll point out here that one of the critiques of the book I read complained about the characters not being there at all. This is silly. I will confess it’s been a long time since I read British fiction of the time, so I was having trouble fully fleshing the characters. But I remember a time when the characters would have been fully fleshed to me, even though the author did not minutely (or otherwise) describe them.

Let me explain, there are… stereotypes in fiction of the time. Archetypes, even. Particularly in British fiction of the time, which often started with boarding school adventures. Describing someone as being blond and handsome was enough to unleash a whole stereotype in the reader’s mind, which has nothing to do with the unpleasant Arian stereotypes in ours. As I said, I’m no longer in touch with those, but back there in the detritus of my mind, pre-brain getting rattled couple three times, those stereotypes existed, because I read a lot of YA British literature of the turn of the twentieth century.

As an illustration, in Pyramids, when the boy in the Assassins league school tries to sacrifice a goat, Pratchett is playing with exactly those stereotypes: the religious boy and the young leader who defends his piety. It’s beautifully done, and probably completely misses the mark with modern American audiences.

Anyway, the lack of characterization didn’t bother me.

What bothered me are the things that happen in the space flight. They bothered me so much that I had to take breaks just to make sure I wasn’t hallucinating them. (Yes, I know how strange that sounds.)

The whole thing has an hallucinatory feelings and the “science” feels about right for an Uncle Scrooge comic. Take where they take a “super multivitamin” each of them containing 4000 calories. What even?

I remember my older family members saying when I grew up I probably would just take tablets instead of eating, but it never occurred to me they were serious, or that this was once upon a time acceptable wisdom. How did they think that many calories could be compressed… Never mind.

The ship itself is a balloon rocket. Okay. Whatever. I could deal with that. What I couldn’t deal with is that almost immediately in the stratosphere, they come across a dragon-creature who breathes poisonous gas.

There are other incidents, including one in which they breathe? Are hit with yellow? radium rays which almost kill them are are cured with anti-radium rays. (I’m sorry. I read it three months ago and stupidly didn’t make annotations on the book itself, and now can’t find my notebook.) Anyway, at one point one of them is breathing out luminous radiation, but comes back from it, no big. It buffs right out.

They are continuously threatened/interfered with by Martians but the most bizarre thing is that there are random “islands” in the stratosphere which are inhabited by humans that speak a dialect of English and live like English yeomen. Only very advanced, long-lived yeomen because they…

Hold it.

Hold it.

Hold it.

Because they have fountains of ultra violet rays, which cure EVERYTHING!

Anyway, in fact the whole thing has the hallucinatory quality of something that should involve the Duckburg Ducks…

Our heroes escape everything, including nefarious natives, and return to Earth victorious and to much acclaim.

It’s both enjoyable and forgettable, just “summer adventure” fodder which could take place at sea, or in Africa, or anywhere else at that time.

The interest in this one is mostly historical. How little someone who was interested and obviously — it feels painfully like that at times — trying to communicate and popularize what was scientific knowledge actually knew of things outside Earth.

However, there is one point that is almost painfully “nowadays” in terms of science fiction and it’s when the author, through the mouth of the wise old one in one of the stratosphere islands, who tells our heroes that if only everyone on Earth were irradiated with violet rays they’d also live long, healthy lives.

Let that be a lesson to you, children (and adults.) This is why we science fiction writing crackpots should lecture less, not more. These ideas that strike us as absolutely inevitable and brilliant would in fact destroy life on Earth.

Anyway, highly amusing book, as an…. historic document. It’s just, read in our time, it is more fantasy than science fiction.

Onward. Next week Festus Pragnell, The Green Man of Greypec. (Which I reviewed in 2016, but considering what that year was like, and that it’s been ten years, I’m going to read it again and let you know what I think. I’ll write about it Tuesday or Wednesday next week.)

And tomorrow we’ll talk about “why teach “literature” at all.

So, some dispatches from the Great Gatsby War™. This is really another border skirmish between people who read what they’re told, and people who read for pleasure. I’m going to suggest that the “read what you’re told” people and the “read for pleasure” are missing an essential point, and that is that you have to learn to read for pleasure too. The core issue here is that the “read what you’re told” people don’t understand that, or just don’t care, while those of us who do read for pleasure are unhappy not just that our stuff isn’t being read, but that the “read what you’re told” people are actively discouraging reading for pleasure, whether they know it or not.

I learned to read sometime before 1960 in Alamosa, Colorado, which is pretty much the definition of a little tiny prairie town. It had a college (Adams State College then) that was primarily a teacher’s college, and its main claim to any sort of standing as a town being that with a population of all of 7500, it was the closest to a major metropolitan area closer than Taos, two hours away. And Taos was a little bitty artist’s colony.

Still, I started reading early — I can’t really remember a time when I couldn’t read. Most of what I read at first was comic books, but when I was about 8, I progressed to Tom Swift, Jr, thanks to a couple of books I received for Christmas. But by then I was hooked.

But I also knew I wasn’t supposed to like that stuff. My parents really didn’t like me reading comic books and I had to beg for quarters to walk to the Arapahoe grocery store to buy them. Two of them at a tine, they were 12¢ each then. And the “appropriate” books in the tiny corner bookstore were all “appropriately” boring for an 8 year old boy. Besides, I read much better than the kids books at the time.

Time passed, and I continued reading for pleasure. Soon enough, I read well enough to start in on my father’s books, of which he had a crapload, being a pleasure reader himself. I read many of the Hornblower books, and then, because I liked sea stories, my father handed me Moby-Dick. I remember I made it as far as the chapter on Whiteness before I said “what is this crap?” and put it down. But there was lots more to read — I managed to buy a couple more Tom Swift’s with birthday and Christmas money, and then — foreshadowing music please — my father, tired of me begging for more to read, handed me Heinlein’s Stranger In A Strange Land. And from then on I was a science fiction fan, reading all the Heinlein I could get ahold of — Heinlein at least was actually in the Alamosa public Library. That was followed by Asimov, Clarke, Poul Anderson, all the greats. I was thoroughly hooked, reading probably 50 or 100 books a year.

The whole time, teachers were telling me I should read good fiction, or histories, or dry as dust biographies. (Not all of them were dry as dust — I remember a biography of Jim Thorpe, who I liked because he was an Indian just like me.)

The thing was, all those good books they handed me were only good in the sense that they fit into the prescribed lesson plans, with quizzes and discussion questions and 15 or 30 page a night reading assignment on which you would be tested.

Honestly, it was downhill from there. I didn’t read as many comic books — my parents had thrown away my two-foot stack when we moved from Alamosa to Pueblo when I was nine — but by then I’d discovered paperbacks, and not long after that Analog Magazine. Which I carried with me and read whenever a chance came up.

Teachers were still trying to get me to read good books. A ninth-grade teacher gave me a paperback copy of Arundel by Kenneth Roberts. I tried but it was full of people doing silly things.

And then I got started on Ayn Rand in high school. Which I loved. And which was also not good literature. My poor English teacher literally fleered when I gave her a book report on Atlas Shrugged.

In grad school, I was reading Hemingway short stories, and my friends who were English grad students tried to get me to read Faulkner and Fitzgerald, including — you knew it had to come up sometime — The Great Gatsby. And I was still looking at it and saying “why?” while they told me how deep all that stuff was.

However, I now had a solid grasp of why I didn’t like them, at least. I was reading for fun. If I wanted to read something with problem sets, I had linear algebra.

About then, I ran into Lost in a Book: The Psychology of Reading for Pleasure, by Victor Nell. It was a study of the psychology of reading for pleasure, something he called ludic reading — which just means reading for pleasure but is far more scientific being drawn from latin ludus, “to play.” It’s a very interesting book — over the years I’ve owned several copies as they got loaned out or sold during a massive book cull — that identifies two main approaches to ludic reading. Type A is reading to calm anxiety, to escape from the ordinary world; type B is reading to engage so deeply with a narrative that it heightens imagination and deep immersion.

I have my doubts about the distinction, but what’s most interesting to me about type B is that measurement with EEGs, heart rates, and eye movement indicated that type B readers were entering a state very much like a hypnotic trance. In fact, Nell called it a “ludic trance”.

Another characteristic of this ludic trance was that if someone was interrupted, it took time for them to return to the ordinary world. It was literally an altered state.

The point I found most interesting was that there was one thing that could pretty certainly prevent ludic reading: being told ahead of time that you’d be tested on the contents. Needing to remain conscious of the text prevented becoming immersed.

I think this is the root of the Gatsby Wars. When a teacher assigns The Great Gatsby today, it’s with the expectation that students are going to have to answer questions about it. While it’s clear some people do find pleasure in reading it — H.L. Mencken, the great cynic, called it “nearly perfect” — but that expectation of being tested on it breaks the trance for most.

In other words, turning it into an academic exercise probably destroys the experience for many people.

A lot of the Gatsby Wars have been focused on people on one side, like Larry Correia, pointing out that they sell hundreds of thousands or millions of copies to people who are reading for pleasure and contrasting that, people sneering that mere genre authors think their books should be taught as literature, har-dee-har-har.

But Larry, and Brad Torgersen, and others on that side of the controversy aren’t actually insisting that their books are Literature, as much as they’re protesting that reading for pleasure has been discounted.

We can check that. First of all, a lot of the books that are taught as Literature today were at the time great commercial successes. People were reading them for pleasure. Dickens’s readers literally crowded the docks of New York City waiting for the next installment of Master Humphrey’s Clock anxiously waiting to find out whether Little Nell was dead.

Shakespeare, often mentioned by some as not being a fun read, I think gets that status from a combination or two factors: first, it really is written in an archaic dialect of English to which a reader needs to adapt; and second, when it’s assigned in class, it comes along with that dread ludus-killer, the questions on the test.

But people did go to Shakespeare’s plays for pleasure — he was famously derided by the elites of the time but he made enough money off the plays to establish an estate in Stratford — and people today read him for pleasure, and go to his plays for the fun of it. (At least sometimes. I’ll rant about what modern productions do to his plays another time.)

I actually started reading Shakespeare for pleasure thanks to an English teacher in High School — Mrs Kelly, not the one who fleered at Atlas Shrugged, which was a shame as I’m sure she could have managed a majestic fleer — who made the class read Julius Caesar out loud, going a few lines at a time from student to student. A lot of my classmates clearly thought it was a stupid thing to do. Gringo kids read in a dull monotone, and the Chicano kids’ accents became much more pronounced, nearly to incomprehensibility. But some of us, the theater kids, got into it, and discovered it made much more sense when read aloud.

And I think that, finally, is the key to the Gatsby Wars. It’s not whether or not Gatsby was a good read — some people thought so, but it was a commercial flop and didn’t take off until it was being assigned in literature classes — but whether or not the teachers teach these books, and other books, as being fun to read.

No, I’m not calling for a French Revolution. As I had to tell an editor at one point — he didn’t take it well, btw — there is a reason I didn’t have my character lead the future French-Revolution analog in the Darkship series. Because the d*mn thing was a proto-communist attack on civilization, as any attempt to impose equality on human society always is. The only equality we should have is equality under the law. Other than that, the only way humans can be made equal is to kill them all. (Which admittedly the French Revolution make a good attempt on, and people like Mao really made a good start on. Though nothing like the total population reduction the WEF has been hankering for.)

However the storming of the Bastille is a good image. Particularly since we now know that the Storming of the Bastille was not what you’ve been told in school, and it certainly is not what the French school children were taught.

It wasn’t a glorious fight, but an episode of deranged mob violence, that freed very few people (who were in the right place) and set the tone for the absolute insanity that was to follow. And yet, it is an important image.

Every July 14th the storming of the Bastille is celebrated in the same way that the fourth of July is here. Well, not exactly the same way. My best friend from childhood married a Frenchman and became a citizen at the same time I became an American citizen. I will tell you my husband bought me a plethora of fireworks and we had much fun that fourth of July, but my friend got to dance with the mayor of her French town, an indignity I was spared. Okay, it’s a joke, son. And not. The french celebration is more “official and top down” as opposed to every American blowing a couple hundred dollars on fizz pop bang and pretty lights in the sky. (Yeah, we have official celebrations too, but it ain’t the same.)

The point being the french are inordinately proud of that bit of mob violence even though it freed exactly seven people:

It’s true that the Bastille was stormed by a crowd, but at the time it was only housing seven prisoners, and none of them were known to have been rebelled against the crown in any notable way. According to records, the seven prisoners in the Bastille at the time were four counterfeiters, two ‘madmen’ and a nobleman accused of sexual perversion.

The thing, though — hear me out — is that it was not the real Bastille storming that is being celebrated. And it wasn’t the real Bastille storming that kicked off the horrors of the French revolution.

No. What kicked off the French Revolution was the perception of the abuses of the elite, the perception of the corruption, money wasting and sheer immorality of the elite.

A lot of that was propaganda. But not all. For instance, their elite wasn’t so much wasting money as truly abysmally bad at administering it — and society in general — at a time of great technological/social upheaval. They were however just as perverse as they were painted, something I didn’t know until ten years ago when a side-mention in a book about something else sent me hunting for personal memoirs and such, and I realized that that part of the incendiary propaganda that led to the revolution was not a lie. Hollywood’s most depraved parties had nothing on the French Aristocracy under l’Ancien regime.

The abuses were probably also true, though not uniformly distributed. I’m sure they had a lot of very decent noblemen doing the best they could, but the problem is that the system itself was so biased that abuses were inevitable and wouldn’t be thought about overly hard. There was no reason to avoid them.

Combine that with the fact that people — individual people, peasants — were growing more powerful in fact due to various technologies, and that this sclerotic elite didn’t even understand the new technologies or how relatively prosperous and capable the people were becoming, and you have the setup for a massive amount of growing anger. The anger of the many against the few who are perceived as holding a foot on the majority’s neck.

The problem is that, for various reasons, including the lack of an idea of individual rights in French society and the fact that intellectuals who felt hard done by the the hereditary class system were the ones stoking the fires of revolution, plus the fact that the ancien regime held on long enough for the anger to build, when it blew up with that major act of mob violence, the French revolution had already lost the plot. Instead of fighting for equal rights or equal opportunity, they fought for equality. I.e. they upended what they had in which some people were superior and deserving of more by birth into everyone being equal and DESERVING OF EXACTLY THE SAME BY BIRTH.

This is the same mistake made by all communists, including the DEI cultists in the US, who assume that if people have different results it must be because of unseen discrimination because — I don’t know, guys, apparently they never met more than one human being? — they think of humans as widgets, who are all exactly alike, and devoid of external controls on them will all do the same and achieve the same results.

The truth, if you need to hear it, is that we are all completely different. We’re CREATED equal, in the sense that we’re all endowed by our creator with the same rights. other than that, we’re all completely different. Take the person I live with, my other half, the person I’m closest to in the entire world. If you asked him to write a political-cultural blog every morning for years, he’d probably try to crawl under the coffee table and braid his hair (It would fail as his hair is very short) in hysterical avoidance.

On the other hand, there are the things he does because he just finds them laying about and no one is doing them, like in the first week of lockdown during the COVIDiocy, he created a program that pulled the latest (some updated daily) numbers of people diagnosed and hospitalized or having died from Covid in every county in the Union.

If you asked me to do that, I … would need ten years. Partly because my head doesn’t even bend that way.

For each of us, doing what the other considers fun, or relaxing, of just interesting, would be considered a form of hell for the other. Even when we read the same non-fiction, our take-aways are completely different. (This is actually great, as we always have things to talk about.)

Anyway, part of what sent the French revolution down that appalling path is that no one was thinking very clearly by the time things blew up and blew into insanity.

The Bastille had in fact been a notorious jail for centuries. People had been consigned to it with nothing but a note from the king. And once in there, they disappeared.

The fact that it wasn’t that by the time it was stormed, doesn’t mean it had not been that before, or that it wasn’t a symbol of what had been done to the French people for centuries.

I would like us to not storm the Bastille.

Look the anger is there, for both good and bad reasons, and though there are a few propagandists — there always are a few propagandists and in this case there are… ah… foreign interests who are very good at propaganda and who are trying to get us to blow up. because the only thing that can destroy America is America. The others aren’t even close to being a problem.

The most valid reason for being angry is the entire lockdown over Covid. A ridiculous ploy that used the virus as an excuse but (I’m convinced) had as its true goal the theft of the 2020 election. All of us were robbed by the lockdown, and everyone is angry about it, including the ones who aren’t aware of it.

Old people died alone. People didn’t get to say goodbye to parents and relatives who died. People’s checkups were postponed or stopped, leading to a lot of cancer becoming lethal when it shouldn’t have been. Children lost years. Older people lost functionality. And there is credible evidence that the vaccine robbed a lot of people of their health. Even those we lost to the virus were lost because the most effective treatments were demonized and forbidden, because they wanted to force their vaccine.

There is a lot of anger just under the surface. No one has forgotten and only true saints have forgiven.

But what the entire thing and the subsequent steal did was show that there was a lot of gaslighting going on. And break people’s trust in government. (At least as much as the black plague wounded faith in G-d, or at least in the church.) People’s trust in science and the institutions is also pretty shot.

This leaves us with a very big drop before we find things we believe in.

It is people’s — relative — trust in the new broom, in this case Trump and the people he brought in, and the fact that we managed to overcome the margin of fraud in November, that is keeping us from falling through the thin veneer of normalcy and go insane.

Let me put it this way: when the people find out that they’ve been preyed upon by monsters, it is important that the monsters’ be exposed and slain.

You can either do it by letting the crowd run mad and kill real people, a process that tends to end with everyone being killed in turn, because revolutionary fervor becomes private vengeance and envy, and Madame Guillotine is always hungry, or you can slay the processes that allowed the abuses to happen. The processes that created monsters.

We have a lot of processes that need to be reformed, and G-d bless and keep people like Data Republican for all she’s doing. G-d bless Musk too, and grant him the ability to land on Mars.

Our Bastille, however, is our secret services.

They were never as good as they are advertised to be. The people who were duped by the Soviet Union certainly don’t know everything that happens in the country and they don’t control much of anything.

But are they as monstrous as the Bastille? Are they capable of bringing disproportionate punishment and perpetrate random and horrific evils for reasons that seem unfathomable to us and might very well be unfathomable — or just corrupt — for them?

I don’t know. And neither do you. We do however have suspicions. We have legends of men in black, and we attach our suspicions to things like the Kennedy Assassination; the MLK Jr assassination, and yes, Epstein’s list.

Look, I’m iffy on the first two, and the last I’m fairly sure was some kind of a secret service honeypot operation, a way to have blackmail on people.

The first two … I’m fairly sure JFK was killed by the Russians and G-d only knows why and how MLK Jr. was killed.

Epstein, though… The list might or might not exist where the government — the official government — can get to it. But it is important.

My only caveat is that I think people on the street care less about Epstein — they assume everyone rich or powerful is a perv — but care a lot more about MLK Jr. and JFK. There is a subgenre of literature about those assassinations. They haunt the public imagination.

However Epstein could flare into sudden relevance and become a focus of anger with very little propaganda effort or — and more likely — by something coming out that centers on it. Not even on the goings on, but on the blackmail resulting from the goings on. If someone is proven to have been blackmailed, and if the consequences hit the public hard — say in letting a stolen election stand, for instance — the issue will suddenly flare up, as the sudden hatred for the Bastille flared up.

Not only did ninety something attackers get killed in storming the Bastille, but the governor of the Bastille and the guards — who were, by that time, innocent men — were dragged out and killed.

Listen to me: I don’t know if ANYONE reading this has an in to Trump, Vance, Kash or Bondi, but this is very important: it’s not “We’re not hiding anything” or “We simply don’t have that information” that is going to save us from the madness of the French revolution.

The monsters MUST BE SEEN TO BE SLAIN.

The only thing that could have stopped the French revolution in its tracks would be for the governor of the Bastille to throw open the doors and show who was there, and why, and more importantly WHO WASN’T THERE.

I don’t care if there’s no there there for the assassinations. And I don’t care if Epstein’s list doesn’t exist all in one place. The games that Bondi played around the would-be release told us that she’s either a fool or a villain. She either lied, or she got rolled.

Either way, it means a core of the ancien-regime holds on, and who knows what hides in the deep recesses of the ancient and evil prison?

Who knows what our secret services have been up to? Who knows who they serve? We have reason to believe it is certainly not the people.

THE DOORS MUST BE THROWN OPEN before something happens that causes a crowd to coalesce and go insane.

Mr. President, you promised. And I will grant you that you are our Vimes, or perhaps even our Moist Von Lipwig, which means you’re working behind the scenes to get the results you want. Or for those who don’t read Pratchett: our president is so twisty he can go down a corkscrew without touching the sides.

But you promised. You are our new broom, and we’re trusting you to sweep.

Your time is limited, and you’re at the mercy of a sudden and explosive event. The clock is ticking.

I don’t want us to storm the Bastille. And Madame La Guillotine should stay in France, where — if anywhere — it belongs.

But the only way to avoid the storming of the Bastille; to make sure it doesn’t happen, is to open the doors, and show what is and isn’t there.

It’s time.

If you wish to send us books for next week’s promo, please email to bookpimping at outlook dot com. If you feel a need to re-promo the same book do so no more than once every six months (unless you’re me or my relative. Deal.) One book per author per week. Amazon links only. Oh, yeah, by clicking through and buying (anything, actually) through one of the links below, you will at no cost to you be giving a portion of your purchase to support ATH through our associates number. A COMMISSION IS EARNED FROM EACH PURCHASE.*Note that I haven’t read most of these books (my reading is eclectic and “craving led”,) and apply the usual cautions to buying. I reserve the right not to run any submission, if cover, blurb or anything else made me decide not to, at my sole discretion.– SAH

FROM JEFF DUNTEMANN: The Everything Machine

Carrying 800 passengers and their household goods, agricultural animals, and farm-related supplies to Earth’s first interstellar colony, starship Origen’s hyperdrive self-destructs, marooning its passengers near an Earth-twin planet orbiting an unknown solar-twin star. While settling in, the inadvertent colonists name their world Valeron, and discover that Valeron is scattered with hundreds of thousands of alien replicator machines—but there are no aliens nor any other trace of them.

Each replicator is a shallow 8-foot-wide black stone-like bowl half-full of fine silver dust. Beside the bowl are two waist-high pillars about 8 inches in diameter, one pale silver, the other pale gold. Tap on either pillar, and the pillar makes a sound like a drum, one pillar high, the other low. Tap 256 times on the pillars in any sequence, and something surfaces in the bowl of dust. Simple sequences create simple and useful things like shovels, knives, rope, saws, lamps, glue and much else. Complex or random sequences create strangely shaped forms of silver-gray metal with no obvious use. 256 taps on the pillars can create any of 2E256 different things; in scientific notation, 1.16 X 10E77.

That’s just short of one thing for every atom in the observable universe.

The artifacts are dubbed “drumlins,” for the sounds the pillars make, and the replicators called “thingmakers.” Drumlins have strange properties. Although virtually indestructible, drumlins can change shape, especially when doing so will protect a human being from injury. Drumlin knives will not cut living human tissue, but they will cut living animal tissue or human corpses. Press a drumlin knife against your palm, and it will flow and flatten out to a disk. Pull the knife away, and it will slowly return to its form as a knife. Some claim that drumlins read human minds and grant wishes. Others insist they are haunted by invisible and perhaps hostile intelligences.

After 250 years on Valeron, the colony prospers. Starship Origen is still in orbit, and a cult-like research organization called the Bitspace Institute vows to repair Origen’s hyperdrive and return to Earth. With millions of drumlins catalogued using the thingmakers, Valeron’s people live well and begin to lose interest in returning to Earth. This threatens the Institute’s mission, prompting it to launch a covert effort to undermine public faith in drumlins. A low-key war begins between the Institute and those who value drumlins–including farmers, rural folk, an order of mystical women, and several peculiar teen girls who have an unexplained rapport with the thingmakers and their mysterious masters.

FROM HOLLY CHISM: Escape Velocity

An optimistic collection of six stories revolving around leaving Earth, or living (and making a living) further out in the solar system.

Xanadu–Sometimes, making a profit just needs an outside perspective for why it hasn’t yet.

Turing’s Legacy–It takes love to make a person. And maybe an accident.

Theory in Practice–Psychological care may well be more important in a closed environment.

Reasonable Accommodations–Microgravity could be an answer to some disabilities.

You Can’t Go Home Again–The effects of long-term isolation on asteroid miners explored.

Everyday Miracles–What could push someone to emigrate to a new off-planet colony?

FROM EDWARD THOMAS: Secret Empire (The Troubles of George McIntyre Book 3)

George McIntyre’s troubles are not over, as he and Ginny must learn to get along with their numerous Valkyries and robot girlfriends. And the police, who are reluctant to cooperate. Jimmy Carlson and Kim Park solve the Alcubierre warp bubble puzzle, creating a whole new world of possibilities for trouble. Leading Jimmy to ask Enrico Fermi’s famous question: where is everybody?

Follow George and the Angels as they rescue wild Toasters and find hints of mysterious spacecraft flying past Barnard’s Star.

FROM BRIAN HEMING: The Lives of Velnin: The Black Citadel

Swordfights. True Love. High Adventure. Epic Battles. Action. Magic. Reincarnation.

I was 17 years old when I died for the first time.

I parried the guard’s cut, feinted high, then swung Swelfalster, blade of the fallen star, low for a slash at his unarmored thigh. I scored, a line of blood dripping down his leg, and danced back before his counterstroke landed.

This is the chronicle of Velnin, Crown Prince of Tarmel, told through the dying words of his first incarnations. Vel is sent as a spy to the territory of the Black Citadel, investigating a newly rising power, the dark rumors surrounding it, and the fearsome might of its army: the Black Legion.

In his journey he encounters the charming Aloree, diplomat of the neighboring kingdom of Talore. Healer, magic-user, diplomat, bookworm, her beauty belies hidden secrets within her.

A fast-paced epic fantasy of swords, love, magic, and battles. Vel must protect the people of his kingdom, and make whatever sacrifices he must to end the horrors perpetuated by the Black Legion. But must he sacrifice true love itself for the sake of his people?

FROM DALE COZORT: Jace of the Jungle: A Snapshot Novella (Snapshot Jungle Adventures Book 1)

A Snapshot Jungle Adventure?

Strange new people and animals keep appearing in an alternate history or alternate reality Africa otherwise isolated from the rest of the world for millions of years. In that strange version of Africa, oddly familiar events keep happening.

*An out of place passenger liner is torpedoed by German submarines.

*A castaway boy is raised by man-like apes.

*Brutal slave-raiders sweep in to destroy peaceful communities.

*An 18 year old damsel finds herself in a lot of distress.

*Men talk with elephants.

*Men and ape-man fight to the death.

Sounds like that has all been done before a time or two, right?

Jace of the Jungle delivers an homage to the pulp era Jungle Adventure story with a New Pulp novella just as action-packed as the old pulp adventures. Fair warning, though: Jace starts out considerably darker than the old pulps and goes places the pulp era stories couldn’t.

FROM DAN MELSON: The End of Childhood (The Politics of Empire Book 3)

The die is cast.

The Empire has caught the fractal demons marshalling troops for assault, and there is no avoiding the decisive Armageddon between humanity and the fractal demons. Both sides have their strengths and there is no certainty about the outcome. While the Empire is free-falling towards open war, Grace is tasked with nudging the odds a little bit, ferreting out traitors to humanity, bribed with the seeming of the most precious gift possible but with a nightmare catch.

Then at the moment of the first skirmishes, personal tragedy strikes, clearing the way for a long-delayed impulse, which results in horror and more personal tragedy.

But out of the disaster, a new Grace emerges – one ready to stand on her own, fully realized as a potent force in her own right.

FROM LEIGH KIMMEL: Khuldhar’s War

The war was over, but where was the peace the victors had promised?

Geidliv the Tyrant was dead, and the rogue nation of Karmandios now lay in ruins, its people prostrate before the occupying armies of the five allied nations. But now the winners are quarreling among themselves, and where brothers fight, enemies will enter to widen the gap.

Merekhet is a man torn between competing loyalties, tormented by guilt over his past failures. Raised the scion of a Karmandi noble family, he discovered upon puberty that he was in fact the son of a senior war commander of the telepathic People of the Hawk. Yet he could not entirely disavow his mother’s people, and thus became entangled in Geidliv’s regime and his nephew Khuldhar’s doomed attempt to fight it.

Now Merekhet has evidence that Geidliv used telepathy and the bioscience of the mer-people to create a living weapon from Khuldhar’s genetic material and hid it in plain sight. Worse, a former ally now estranged is seeking that weapon, and must not be allowed to capture it, lest all the world of Okeanos fall to far greater tyranny than Geidliv could ever have hoped to create.

Merekhet must regain Khuldhar’s confidence, and together they must find the five young men who are the keys to Geidliv’s final vengeance weapon.

BY KEES VALKENSTEIN, TRANSLATED BY DWIGHT DECKER: The Vanishing-Machine

What is a vanishing-machine?

Two fifteen-year-old boys in rural Holland find out when they come across an abandoned machine that can make things invisible. They first use it for mischief on the farm, then things get a little complicated when the machine’s American inventor, two bumbling detectives, and the eccentric master criminal who stole it turn up.

The Vanishing-Machine is a humorous science-fiction novel published in the Netherlands in 1917 and translated into English for the first time. With translation notes, map, new and vintage illustrations, and historical background.

FROM SARAH A. HOYT: Lights Out and Cry (The Shifter Series Book 5)

It is New Year’s Day in Goldport Colorado, the most shifter-infested town in the known universe.

At the George — the diner where shifters gather — Kyrie is about to give birth, Tom is getting psychic messages from the Great Sky Dragon and Rafiel is looking for information on why the mayor exploded.

Fasten your seat belts. This is going to be a fast ride into adventure and shape-shifting, after which things will never be the same.

FROM KAREN MYERS: On a Crooked Track: A Lost Wizard’s Tale (The Chained Adept Book 4)

Book 4 of The Chained Adept

SETTING A TRAP TO CATCH THE MAKERS OF CHAINED WIZARDS.

A clue has sent Penrys back to Ellech, the country where she first appeared four short years ago with her mind wiped, her body stripped, and her neck chained. It’s time to enlist the help of the Collegium of Wizards which sheltered her then.

Things don’t work out that way, and she finds herself retracing a dead scholar’s crooked track and setting herself up as a target to confirm her growing suspicions. But what happens to bait when the prey shows its teeth?

In this conclusion to the series, tracking old crimes brings new dangers, and a chance for redemption.

FROM MARY CATELLI: A Diabolical Bargain

Growing up between the Wizards’ Wood and its marvels, and the finest university of wizardry in the world, Nick Briarwood always thought that he wanted to learn wizardry. When his father attempts to offer him to a demon in a deal, the deal rebounded on him, and Nick survives — but all the evidence points to his having made the deal. Now he really wants to learn wizardry. Even though the university, the best place to master it, is also the place where he is most likely to be discovered.

AND OH, YES: Younger DIL is selling this weekend, at the Wichita, KS, Comicon.

So what’s a vignette? You might know them as flash fiction, or even just sketches. We will provide a prompt each Sunday that you can use directly (including it in your work) or just as an inspiration. You, in turn, will write about 50 words (yes, we are going for short shorts! Not even a Drabble 100 words, just half that!). Then post it! For an additional challenge, you can aim to make it exactly 50 words, if you like.

We recommend that if you have an original vignette, you post that as a new reply. If you are commenting on someone’s vignette, then post that as a reply to the vignette. Comments — this is writing practice, so comments should be aimed at helping someone be a better writer, not at crushing them. And since these are likely to be drafts, don’t jump up and down too hard on typos and grammar.

If you have questions, feel free to ask.

Your writing prompt this week is: EFFECT

Coming to oneself means regaining consciousness. I don’t recall ever hearing it used in English, (though the expression is the same) but in Portuguese “vir-se a si” is the expression explicitly used to denote waking from a swoon. (We tend to just say waking. Which I didn’t want to use because of the aggregation to woke which, like all leftist speak means the opposite of the plain meaning of the word.)

I was contemplating this post when in a group a friend linked this post: American Strong Gods, Trump and the end of the Long Twentieth Century.

And I realized if not the main point I was trying to make, it is a strong supporting point. He talks about the end of the long twentieth century in which the whole world aimed for a vague “open society” that was the opposite of nationalism, as a way to fight long-dead-Hitler (Or prevent a recurrence of fascism.) And how Trump is the long-delayed end of this.

Put a pin in this, because we’ll revisit it.

First: We have been working late and a lot, and therefore coming downstairs late and with our minds turned to mush. So, we’ve been doing what we normally do, which is watch some kind of series on something or other. in this case we’ve been watching a series, per decade, on inventions that changed the world.

And both of us noticed that other than computers, the inventions they showed, after the seventies, were not inventions that changed the world, so much as things at the margins, and increasingly more and more things at the margins.