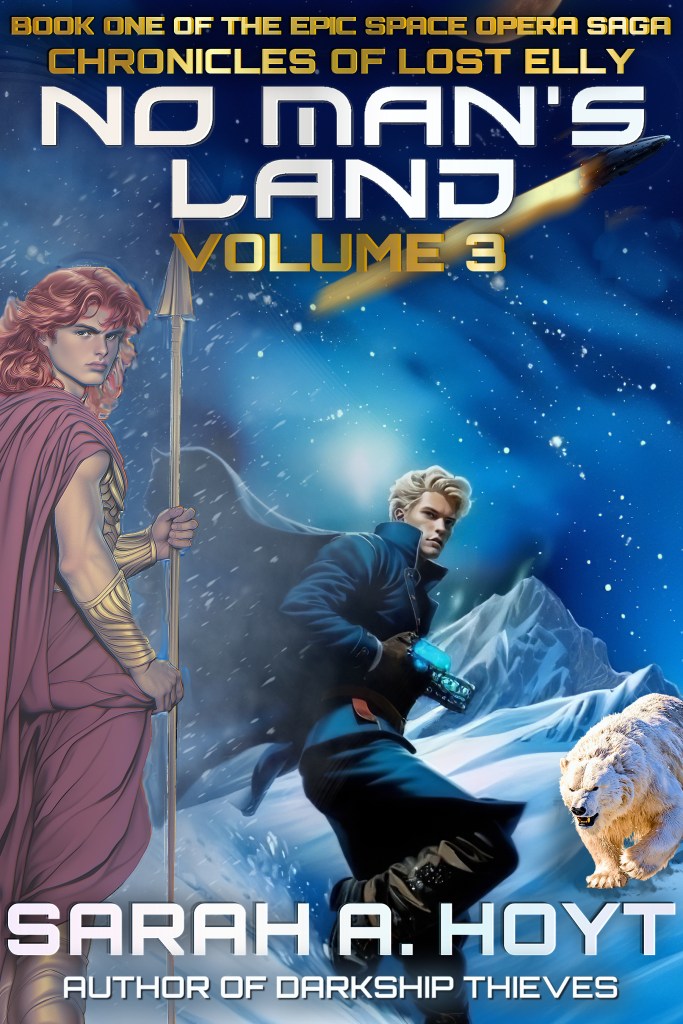

I spent the day going over the copyedits for No Man’s Land 3 which shouldn’t be so incredibly tiring.

This is by way of being, basically a state of the writer post. I still haven’t managed to do any real writing since mom died, and…. well…. sometimes I even come up blank on blogs. (See today.)

So I thought I’d share with you another of the …. snippets from Elly.

For those who haven’t read No Man’s Land (if you’re waiting for the omnibus, it will be electronic only and probably only in December, just on having time to do it… This year has turned super-interesting) it is a lost colony of bioengineered hermaphrodites. I chose to use masculine pronouns, mostly because the breed has no breasts, and using “she” immediately brings up a woman’s figure. Also, to be honest, using “she” seems to call for some kind of feminism, which this isn’t, really.

Anyway, this story takes place between book one and two (not volume one and two, but No Man’s Land and Orphans of the Stars.)

The characters are Selbur Deharn, who is technically (but not really) a Brinarian nomad and who had a child by the king. Since the child is Brundar Mahar’s sireling, he’s technically the heir to the throne, so they make the poor critter move to the royal palace, where he’s like a fish out of water.

Another — er — fish out of water is Nikre Lyto, who is Brinarian born and the adopted child of the former king and (still current) archmagician and legally crossibling of the king. Who is also a bit of a fish out of water in the palace, and also extremely shy.

To add another layer to this, Nikre is the most powerful person in the Brotherhood of Magicians (it’s not real magic, but… bear with me.) And Selbur is the head of eighth circle, a circle known for illusions and mind manipulation, but also the lowest power in the brotherhood. (The circle assignment is a “bend” of the power as well as amount. It also involves personality.) 8th circles “snakes” are generally looked down upon/distrusted by all the other magicians.

Oh, and this is about as “sexy” as the book gets. Actually, there’s more sexy talk in this than in the book. (And it ain’t much.)

Jewels

Nikre Lyto:

I don’t remember when Selbur – Eerlen insisted that since he was now related to the royal family we should all call him by his first name – started to come and sit by the koi pond while I sat there and Missa played by the low wall to the pond.

There was no danger to the child, not even when he leaned over to look at the colorful fish. Years before my birth some magician had set a safety spell over the pond. You could dip your finger or your feet in the water, but you couldn’t actually dive in. Unless you were an adult and fully conscious. Since the water was at most two feet deep, there was no way a conscious adult could die in it.

I’d loved the koi pond my entire life in the palace, and little Missa, now almost two years old, seemed to love it just as much. It was a vast, tiled pond surrounded by an ornamental low wall, inset in an ocean of well kept lawn, surrounded by shrubs and a wall.

You could get access to it from the family quarters of the royal palace via a long staircase down, or via portal if you were related to the royal family or had been granted access. There was no other way in.

Missa and I were part of the family, if strangely and on the edge, and had spent many hours in this green, shaded oasis, he and I, as I pointed him at the bright spotted koi which were my favorites, some of which I had named when I was not much older than he. I liked Missa. He was a bright child, with a taking personality, but unlike his sire, my crossibling, Brundar, King of Elly, he was also restful. He would laugh and run and play, but he could also sit for hours quietly watching the fish, while his nursemaid watched, and I sat on the low bench and sewed or read in peace.

I didn’t pay attention when his birth parent started coming along, and sitting on the long stone bench, at the other end from where I sat. It took me even longer to see what he was doing.

I’d thought he was sewing. He had a neat, round, about-knee height work basket, of the sort people carried their sewing around in. It seemed to have a lot of other little baskets inside, which was also normal for sewing baskets. And I’d never looked.

It struck me all of a sudden that sewing of the sort that required a basket was a strange occupation for a nomad, much less a Brinarian nomad. And I’d seen something glinting between his fingers. So I turned to look.

He was twisting silver wire with a very small pair of pliers. No. The wire was so thin as to be almost thread, and he was weaving it into a band, using a small pair of pliers. I think the words “What in the Maker’s—” were out of my mouth before I thought them. Though I stopped myself before finishing it.

Selbur looked up and grinned. He has a face like a cat’s. Um…. That sounds strange. No, he doesn’t have whiskers or muzzle or even vertical-slit eyes. He just has an impish face, with eyes a little too large, and a tendency to look as though you amuse him greatly, no matter what you’re doing. Which is an improvement over when he was first forced – coerced? – into living in the palace. As the parent of the only descendant – sireling – of the king of Elly, he couldn’t be allowed to roam Brinar on his own with his child and a bed roll. Not these days with mercenaries of various worlds passionately interested in us. So he’d had a choice of living in the palace or utterly relinquishing custody of his child, little Amissar Deharn. He’d chosen to keep Missa, but spent his first six months in the palace glowering at every one from the king to the servants.

I didn’t realize till that moment that his expression had changed recently. He didn’t precisely look contented, but he looked at peace and faintly amused at everything.

There was nothing faint in his amusement at me. “Bracelets,” he said. “And necklaces.” He held up the woven strip of silver wire, with a crystal entangled in it.

I frowned at it, then cleared my throat. I knew – none better – that it took time to get used to being part of the royal family and to the immense hereditary wealth of the Mahars. Also, to be fair, I’d never had much interest in jewelry, though I had a few good pieces that my sire, the last king of Elly, had given me. But still… “You don’t have to make your own!” I said. “I mean, I know you won’t ask, but I can hint at Brund you’d like some baubles and I’m sure he’ll give you a choice from the not-bound-to-the-line jewelry box.”

He laughed at me. Delightedly and openly. And no, there was no denying he was laughing at me, though he did it in a way that wasn’t mean, just amused, as though I were being very odd. “No, silly,” he said. “Not for me. And Brund has already demanded I pick jewels from what appears to be a vast chamber in the basement. Because he thinks I dress too plainly for my connection with him. Apparently Brinarian nomads are supposed to be better dressed. I threatened to pick toe rings.”

I blinked at him. Toe rings was a Brinarian thing. Displayed on bare or sandal-wearing feet, at festivals, they meant the wearer was not picky about whom he’d take as lovers. Selbur blushed as I blinked. “Not that I meant it,” he said. “But it got him to stop.” He shook the strip of woven silver wire at me. “These are not for me. I sell them.”

My blinking intensified. It’s a bad habit when I’m trying to understand what I see. “You sell jewelry?”

He nodded. “At festivals and gatherings. And parties.”

I understood he didn’t mean gatherings and parties in the palace, but those he’d be asked to as an eighth circle.

In case you’re an outer worlder and I need to explain eighth circle. They’re weavers of illusions. Which means at parties and gatherings, they’ll recreate or create stories about past figures, or invented ones. You know, Amissar Mahar leading the slaves out of Draksah. Or Irt and Eefahan’s romance. Or—

That sort of thing, vividly, happening before your eyes. Eighth circles get hired to create such shows, and usually paid handsomely, but selling jewelry seemed a weird endeavor.

As I continued staring Selbur huffed. He dove into his basket and brought out a leather strap, the simplest of necklaces, with a crystal on a woven silver cage hanging from it. “Here,” he said. “Hold it. I … made this one for you.” He blushed, as he said it, but scooted close anyway, and handed me the thing.

I was both shocked, and somewhat puzzled. I had jewelry. I rarely wore it, but surely he’d seen me wear it when I was required to be at public functions.

And I couldn’t understand why he’d have made something for me. But he had, and he was trying, so I slipped the leather loop over my head, and let the crystal hang at my chest. “It’s very pretty,” I said. “Thank you.” It was pretty, the seemingly random silver threads letting the crystal shine through.

He smiled and shook his head. “Yes. But—” He sighed. “Put your hand around the jewel and let it open.”

“What?”

“Just… Put your hand around it. Hold it.”

I obeyed.

Suddenly and inexplicably, I was submerged in water. Okay, it was visual only, and a sense of coolness. I could still breathe fine. Around me, colorful koi swam, weaving near me as though I were a particularly interesting reef. My hair moved as though in wind, and they “swam” through it.

It was… once I realized what was happening, both delightful and restful. As I thought this, a bright yellow koi swam towards me and nibbled gently at the tip of my nose. I dropped the jewel, and turned to Selbur, as the illusion dissipated. “That was you!” I said. “The yellow koi.”

He laughed delightedly. “Yes. That was me, inserted in the illusion.”

“You make illusion crystals?” I asked.

“Most eighth circles do. Only it’s expensive, food wise. It takes a lot of energy for us low-circle. Normally I could make one or two a week. I thought since I was living in the palace and have unlimited food, now I’m no longer nursing, I could do two or three a day. And I’ve been trying for more elaborate settings.” He picked up the silver strip, and brought the two ends together, then handed it to me. “Would you fuse the ends for me?”

I gave the thing a burst of energy, neatly fusing the ends together. “How do you do that normally?” I asked. It’s not that eighth circles couldn’t expend that energy, but it would probably cause him to sleep for two days.

He grinned at me, looking exactly like the yellow koi, even if not. “I get a high circle to do it for me. Thank you.” He took the circle back. “Usually my sire, to be fair. He’s only sixth circle, but high enough. But Brund will do it without thinking. And I once got Eerlen to do ten in a row, before he realized what he was doing.”

I grinned at him. “You’re used to getting your way with a smile…” I said.

“Yes. The last months have been a lesson to me that there are things I can’t get my way on, smile or tantrum.”

He looked so wistful, I tried to distract him, “What are the other crystals?”

He shrugged, “Song performances, or quiet forest glades, or gardens. I do one for children that has butterflies flying around. It can keep toddlers amused for hours.”

“Do they sell well? I’d think—” I stopped. I’d been about to tell him that surely nomads had enough of quiet forest glades and butterflies they didn’t need to buy them. But I realized he probably didn’t sell to nomads, not at gatherings, but to crafters and merchants in cities.

However he curled his lip and his face looked sullen as it hadn’t in months. “Those!” he said. “I don’t do those.”

I had absolutely no idea what I’d said wrong, or why he looked like that and then he said, “Yes, erotic illusions sell much better, at least at large gatherings and to nomads, but I can’t do them. And I wouldn’t even if I could.”

He looked so angry, I tried to appease, “I didn’t mean—”

“First,” he said, still angrily, “The illusion either comes from our own experience or from– We can take from people’s memories, but I don’t do that without permission, and not—Not that kind of memory.”

“I didn’t mean you should do that,” I protested. “I was thinking something silly about nomads and forest glades.”

He stopped. “Oh.”

“But now that you started, I’d like to know your reasons. Because I suspect if illusion gems are a way that your circle makes money, that is the most likely way to do it, and I’d like your reasons.”

He hesitated. He opened his mouth, closed it. Opened it again, then sighed. “Well, I can’t do erotic illusions because I simply don’t have the experience on my own. I mean… twice with Brundar, but how do you think Eerlen would take to my selling the experience of sex with his sireling, the king of Elly?”

“Not well?”

“Which is a funny way to say ‘he’d cut you to ribbons.’ Though Brund himself might laugh, I’ll note. But also, second, my experience with Brund is not what people pay for.” He looked up, blushed. “Look, I know it sounds stupid. You’d think that nomads would pay for any sex illusion. Particularly Erradian nomads. I understand it gets lonely in the ice and snow. But most people who buy erotic illusions buy for the…. Exotic. I have heard the talk among those of my circle. To have the experiences people buy, you need to go out, find perfect specimens and do… well, fairly strange things with them.” He was blushing very dark. “I am not… I will not do that. I don’t … I don’t trust easily. I’d hate to be that intimate with a stranger, much less to ask him to do… things…”

I was less experienced than he, but I had heard about “things” and also read some in the old palace diaries and memoirs. “I don’t blame you,” I said.

He inclined his head, “And also even if I could have or steal the experiences, I’m only an eighth circle, and I can’t put protections on those, so only adults can use them.” He looked up and his gaze met mine. “My parent had four of them. I knew they did something, because he’d put one on at night, and he acted funny, in his hammock. So one day, when I was eight and he was hunting and I was minding the littles, I tried one of them—” He looked down and was silent a long while. “It was horrible. I threw it into the river. And later—” He shrugged. “Call it why I’ve only had two experiences and with Brund whom I was friends with. Still am. I couldn’t– There were people who tried—I talked about it with my sire, when next my parent dropped me at the farm to … well, because it was cheaper than feeding me, and my next oldest sibling was old enough to watch the children. And he explained everything to me, and also that what I’d experienced wasn’t normal. But it still left scars.”

I felt incredibly sad. For Selbur. For his sire. His parent… Well, his parent was known to the brotherhood as trouble. He didn’t have power, himself, but he tended to get involved with magicians. And predatory and insane were not misapplied to him.

I’m not, as a rule, easy with words and feelings. I wanted to cheer him up, to tell him it would be all right. But I couldn’t reach through time to console little Selbur, and my gathering him in my arms and holding him might be taken amiss. So I said, “You said you can make jewels with other people’s experiences.” As he turned, as though to protest, I said, “Not that. I mean, what kind of experiences? Do people commission them?”

He looked divided. Then nodded. “Swearings,” he said. “And watching their children play. And sometimes a really good hunt or something. They ask, and they remember the moment intensely and I capture it into an illusion in a crystal. Those are more expensive, because, you know, they’re one person, tailored.”

I nodded. “Selbur? You do realize as parent of the heir, or even, should Brundar have another child, one of the heirs in potentia, you’re entitled to a stipen—”

He was shaking his head. “No. I don’t take money or gifts because I had a child. My parent was always bleeding my sire dry, and telling him I’d starve to death if he didn’t support all of us, my parent and I and my siblings lavishly. All because my sire can’t have children and I’m his only descendant. And he’s vulnerable. I won’t do that to Brund. Missa happened, and I’m glad, and I love my child, but he’s not a money-tap. I am a magician, even if I must seem like a small-power to you. I can support myself. And if the magic fails, I spent enough time on my sire’s farm, I can hire as a farmhand.”

He was glowery again. I liked him better when he was mischievous. I reached out a hand and touched his wrist. “I didn’t mean to offend you, Selbur Deharn.”

He looked up my arm, to my face, then shrugged, and the storm calmed. “No, you probably didn’t. I’m sorry.” He reached into his basket, and brought out a spool of silver thread. “I just… Most high circles or non-magicians who first find that I can and do make these jewels for sale assume—”

“I wouldn’t,” I said. And it was true. Most people would assume things about Selbur because of his parent, but even Eerlen had come around to realizing Selbur was nothing like his parent, and that he wouldn’t – so to put it – wear toe rings, though he might threaten Brund with doing just that. “I’ve come to know you. I wouldn’t assume that of you. Not that it’s… If people want to make those jewels, and if people want to buy them, it’s their problem, but I didn’t think you were the type to do either. And I know you’re absurd about wanting to pay your own way.”

He slanted his eyes at me. “It takes one to know one.”

I laughed. “Yes, Lord Deharn. I do spell stasis boxes and portals for money. But don’t assume I’m as noble as you. I do live in the palace for free, and eat at the family table most nights. I donate most of my earnings to the King’s Children.” Which is the orphanage that gathers unwanted babies into a farm owned by the Mahars.

He nodded. “I heard. Everyone knows.”

There was a long silence, while he worked at the silver to start another bracelet. Then he set it aside, and sighed. “You know when I said I don’t take other people’s experiences without permission?”

“Yes?”

“Well, sometimes people are quiet and are relieving things so vividly that an eighth circle can’t help but live them.” He was quiet a long time. “If you’ll not challenge me to a duel. It wasn’t done out of evil…”

I was thoroughly alarmed, “I beg your pardon?” I raked my memory for some off color experience I could have been reliving. I liked this area for a reason, and yes, there were things I relived, but they weren’t that.

“You won’t challenge me?”

“No, but what…?”

He sighed. “I meant to give you this, but not yet. Like the koi, I made this for you.” He dove into his basket and brought out a rosy crystal, rough hewn. It didn’t have a setting, yet. I reached out and took it in my palm. He nodded at me. I closed my hand.

In the illusion, a portal opened in the middle of the garden, and through it stepped my sire, alive and well, and looking huge. I realized I was seeing him through my very young child eyes, probably no more than six. And that Brundar was there with me, aged maybe two.

Myrrir Mahar was tall, and broad shouldered, blond and blue eyed, and in my memory-illusion, wore a fine knee-length linen tunic, and his blue magician cloak. Which probably meant he’d been on a healing call, as a third circle healer magician, I now realized.

He looked tired as he stepped through the portal, but grinned wide as he saw me and Brund, and chuckled at us. “Ah, my two trouble makers,” he said. And stooping, he gathered each of us into one arm, kissing first Brund’s forehead, with “My warrior.” And then mine, with, “And my Archmouse.” He hugged us close, asking, “What have you done today besides bothering the fish?”

He was warm and solid, and I could hear his heart beat. He smelled of herbs and firelight, and it made me feel utterly loved, utterly safe.

I took a breath, two. I opened my palm, realizing my face was wet with tears.

“I’m sorry,” Selbur was saying. “I’m sorry. It was such a strong memory, and I thought you might like it. I didn’t realize—”

“It is a strong memory,” I said. My voice wobbled. “And I like it. I think Brund might like its twin. Maybe for harvest feast? From me? I’ll pay you.”

Selbur, who had gotten up and looked like a forest creature about to bolt, asked, “You’re not angry?”

I laughed through my tears, patting my sleeves for a handkerchief. “I’m very not angry. Thank you, Selbur Deharn.”

He took his handkerchief from his sleeve, but instead of handing it to me, took two steps close, and mopped my face, gently. “You’re very welcome Nikre Lyto.”

It is entirely attributable to insanity that I chose to capture his hand then. And inexplicable that he did not pull away.

After a while, I pulled back and he pulled away. He talked to Missa’s nurse, then walked away.

When he was not at dinner, I thought I shouldn’t have held his hand. What was I thinking? We weren’t even friends, much less … anything else. Besides, which, I shouldn’t even aspire to anything else, regardless of what my idiot mind and heart conjured.

What they conjured was the feel of Selbur’s hand, surprisingly calloused, and an image of his toes, adorned with tiny silver rings. Not that he had any cause to wear toe rings, but the image stayed with me. For all the good it did me. He wasn’t in the garden the next day, and I told myself that I had overstepped badly, and was lucky he’d not decided he needed to cover it in blood. He was a nomad, after all.

Eerlen had taught me to duel – fortunately, as I’d had to do it twice in my life – but I didn’t think I could strike out at Selbur. Even if I didn’t like him – and I did – he was Missa’s parent. I couldn’t orphan Missa. Who came to get me from my bench that afternoon, and led me to the koi pond, to point at fish and demand I tell him their names and stories. He couldn’t yet talk, but he was insistent in pointing at each of the fish until I told him the name and what I thought was the origin of the fish, and who his offspring looked to be.

When he was tired, he pulled me by the hand to the bench, clambered on my lap and fell asleep there, thereby ignoring his nursemaid. Who just smiled.

Unable to work, I was almost asleep, myself, when I heard Selbur’s voice, in front of me. “I see you have been sweet-talking my line-child, Archmouse!”

Anyone else, and I’d have protested the pet name my sire had given me, and which only my sire had ever used for me. But there was a gentle arching smile in Selbur’s face as he said it, a teasing challenge in his eyes that made the name entirely appropriate on his lips.

I rumbled, my voice sleep-thickened, “More like he’s been sweet-talking me.”

Selbur dropped by my side. He was wearing, I noted, a fresh linen tunic, ankle length, and practical work boots. His hair was taken up and pinned in a messy bun. If he were an upper circle, I’d assume he’d been called away on an emergency. He leaned over and caressed Missa’s dark hair. The child moved in his sleep. “That is a feat,” he said. “For someone who can’t speak a word.”

“He points and grunts very eloquently.”

Selbur laughed. “Does he ever. Normally it means “I too like that food on your plate.”

“In this case,” I said, adjusting the child’s position on my lap. “It was a request to tell him stories of the koi.”

“I should make him a jewel like yours. Will help him sleep. He does love those fish.” He raised an eyebrow at me. “Perhaps it’s something about growing up in the palace?”

I shrugged. “In my case, I think it was because I missed the fish.”

He looked puzzled.

“I came from a fisher village. I mean, you know I’m not Eerlen’s and Myrrir’s natural offspring.”

“I know the story,” he said, and looked away into the middle distance. “Among my many not favorite things of living in the palace is how everyone gossips.”

I laughed. “No. But … fisher children and certainly I, since I was often unsupervised, play in shallow pools, where there’s often tiny fish. Here– Well, the koi were fish, and they were bright and colorful, and interesting. Eerlen used to bring me to see them.” I paused. “I didn’t speak for a few months after they brought me here, and Eerlen did anything that seemed to make me happy.”

“Couldn’t you speak?” he asked, curiously.

I shrugged. “I don’t know. It’s all clouded in my mind. I think I could? But … I’d been feral for a year. I understood language. I understood Myrrir telling me I was his sireling now. But I don’t know if I understood I could talk to people.”

He tilted his head looking at me, but didn’t say anything. Instead, he took off a bag I hadn’t realized he was carrying on his shoulder. It was a small, leather satchell. At that moment, I heard steps behind us, and turning back saw Missa’s nurse walking towards us, carrying a tray.

“I asked him to get us tea,” Selbur said. “And some of the raised bread from the kitchens.” He moved away from me, and the nurse set the tray between us, then bent back to retrieve Missa from my lap. I must have hesitated, because Selbur said, “Let him take my little troublemaker. He’ll sleep better in his bed and be in a better mood at dinner with his royal sire.”

I let the nurse take Missa. Not that Missa ever misbehaved at dinner. Well, not by being angry or loud. He did get in a mood, though, where he would hop from one lap to the other and disrupt everyone’s dinner. Unfortunately unlike Kitten, Eerlen’s child, or Irid, Lendir’s child, Missa’s presence at the very public dinner table was needed to reassure people there was an heir, even if not a child of Brund’s body.

Selbur brought cheese out of his bag and set it on the tray. Several small wedges. I raised my eyebrows at him, and he smiled at me, “I brought you cheese, Archmouse. You’re too skinny. No one will want to tumble you if you don’t put some weight on.”

I made a skeptical sound, as he poured tea into one of the two clay cups next to me, and another in front of him. He added a tablespoon of honey to mine, having somehow known my preferences.

“How would you know no one wants to tumble me?” I asked, taking up the cup.

He gave me a delighted cackle at my rising to the bait. “Gossip, remember? Gossip is many have wanted, none have succeeded. Both here.” He made a gesture encompassing the palace. “And in the brotherhood.”

“People have strange ideas of what is interesting gossip,” I said.

“Archmouse, you’re the Archmagician’s body child, the sireling of a king.” He gave me an up down look so obviously evaluating that I almost dropped my cup. “And don’t appear to have an extra head, be missing a limb, or have a tendency to smell bad. What is shocking is that no one has knocked you on the head and tumbled you before you realized what’s happening.”

“I have protective spells.”

“I wonder if that is the truth or a joke.”

“A joke,” I said. “My true defense is that Eerlen taught me to duel. And Myrrir taught me sword play.”

“Mmm. Your family’s fascination with bladed weapons is either admirable or insane.”

“I suspect yes,” I said. He’d cut the cheese into little slices, with his ankle knife, and I took a small piece not bothering with the bread. It was…. Extraordinary. Strong, but buttery and rich. I’d only tasted something like this… I swallowed. “Calenir? You brought me Calenir cheese?”

He waggled eyebrows at me. “Better than knocking you on the head, yes?”

When I didn’t dignify that with an answer, he smiled. “My sire is Calenir of Calenir. Didn’t you know?”

I shook my head. “I think… around Missa’s birth, a servant said you were at the farm, but I thought… Calenir of Calenir?” I must explain what that meant and why I was staggered. To begin with, I knew that Selbur wasn’t pure Brinarian, though that was the place he identified as his home. And his parent was a Brinarian nomad. Selbur was too tall, lighter skinned than even I – and I was light for a Brinarian – and had blue eyes, even if they were so dark you only noted the blue when the light caught them. Also his features weren’t quite Brinarian, though don’t ask me to explain that. They just weren’t. They were too delicate, too fine. I had heard that his sire was Lirridarian, which explained the features. Lirridarians are as tall as Erradians, and as blond, but the resemblance stops there. The joke is that if there were enough Lirridarians at a gathering, no one else would be picked up. As a breed– Well, we suspected they’d been refined by the Draksalls for being pretty and having facial features that most resembled the Draksall female features.

But Lirridarians and even dairy farmers are one thing. There were many, many dairy farms in Lirridar, but there was only one Calenir.

Calenir was a line name. At some point, a couple hundred years back, the first Calenir had started breeding his cows and perfecting his cheese process in the deep, wind-swept sea-caves near his farm. The farm had grown and was now a network of farms. His clan had grown along with it, and the central line which owned most of the farms and hired most of the clan, had become ridiculously prosperous. One of the few farmers – crafters, I guess if you consider cheese and butter making were crafts – whose wealth rivaled that of the lords of the land. Their products sold for double what other cheese, milk, cream and butter sold.

They deserved it, too. Brundar sent for their milk, cheese and cream, though not for all of the palace needs.

The Mahars owned two Lirridarian farms, themselves, so it would be wasteful to get all from Calenir. But for special occasions, and guilty pleasures, that’s where we sent for dairy.

Why the line child of a Brinarian nomad would be sired by the wealthiest dairy famer in Lirridar was a mystery. But the bigger mystery was why that child would choose to be a nomad?

Selbur took another slice of cheese, and stretched his feet in front of him, looking towards the koi pond. “I’m his only, you see?”

“His only sireling?”

“His only descendant of any kind.”

The mystery deepened. “But then why…?”

I presume he hopes you’ll give him your second chil–” I cleared my throat and said, “Pardon me. Your sire’s line decisions are not mine to question.”

He laughed, but it wasn’t a happy laughter. “Yes. He does hope I’ll have a second child and give him Calinar as a line name. Because I refuse to take his name for myself and little Missa. He would prefer to adopt me as his line child.”

“But you… owe it to your parent…?”

He hunched a shoulder. I said, “I beg your pardon. Truly none of my business.”

“I owe nothing to my parent,” Selbur said. His voice was slightly hoarse. “Without my sire, I’d not even be alive. I understood he left me with my sire at days old. My sire hired people to feed me. I lived with him till I was five, when my parent came to get me, because he had two younger children, and thought I was old enough to watch them while he hunted and while we did a nomad route. He was right. I was old enough. I stayed with him until I was twelve, when he thought—” He paused. “People were starting to notice me. Not that I wished to be noticed. But it took attention from him. And my next older sibling, Terid, was old enough to watch the littles. So he dropped me at my sire’s farm.” He paused. “Then when I was sixteen, he demanded I become a nomad, or he would duel my sire for kidnapping me.”

I was speechless. “I’d heard of Verit Deharn, but—”

“You didn’t know the extent of it?” Selbur’s voice was hard.

“I didn’t realize he’d treat his own child that way. I’m glad you had your sire.”

Selbur sighed. “So am I, but the thing is, I can’t promise my parent won’t try to kill my sire, if I let my sire adopt me. My sire says he wouldn’t mind. He miscarried, when he was very young, in a way that made it impossible for him to conceive again. And healers say he’s unlikely to produce sirelings.” He gave me a brittle grin. “I’m unlikely.”

“Miraculous, I’d say,” I said. “But surely your sire can afford security and stay safe? Your parent is not supernatural.”

“Madness is its own power,” Selbur said. “But yes, my sire says that too. That he doesn’t care what my parent threatens, he can stay safe. But…”

“But–?”

“He doesn’t deserve that sort of hassle, Archmouse. He doesn’t deserve to be hunted and live with a threat on his life.”

“I think,” I said, eating a slice of cheese. “You have rats in your head, sireling of Calenir of Calenir. I can’t imagine you’d prefer nomad life to living at Calenir.”

“I don’t. Not that it’s– It’s where I was, you know? These few days? My sire still works hands on, on the farms. And it’s calving season. He asked me to come help. I know—I grew up… They call me young Calenir.”

“Well, young Calenir. I’d take his name and give it to little Missa.”

Selbur sighed. “For the longest time I didn’t even wish to have children, because they might—They might be like my parent. Missa was an accident. But I don’t think he’ll belike that.”

“That… I understand,” I said.

“Oh, is that why they’d have to knock you on the head, Archmouse. Terrified of bearing a wild Erradian nomad?’

I shook my head. “No. My sire.”

The eyebrows climbed. “Myrrir Mahar, king of Elly, my child’s grandsire? The person you still miss so intensely I could read the impressions without trying?”

I shook my head. “My birth sire. The one who seeded me.”

“Oh, the one who tried to kill you? And might have killed your parent?”

I shook my head. “No, my real body sire, not my parent’s sworn.”

Selbur gave me a troubled look.

“Selbur, you’re an eighth circle, not a small power. You’re head of eighth circle. You can read the pattern under the adoption pattern.”

He frowned at me, and I realized while he could he needed to make an effort and he’d honestly never tried. I thought that it was gossip in the brotherhood, but I guessed fear of Eerlen, and possibly Brundar, had kept them quiet.

I saw Selbur’s eyes unfocus as he looked at my pattern. I saw his lips purse. I saw his jaw drop. I waited for the startled leap away from me, for something to reestablish distance. I picked up my cup of tea and sipped, ready to pretend to be unaffected.

He didn’t leap away. Instead, he closed his mouth with a whistle. “Does—” he said, then shook his head. “Who knows?”

“Everyone, I assume. At least everyone in the inner circles. I’m surprised it’s not gossiped about.”

He shook his head. “Never. How? I—I mean, he wasn’t—”

“My parent was sworn, and his swearing wasn’t broken, so it wasn’t consensual.” I sighed. “When I figured it out, when I was apprenticed as archmagician and saw the pattern that looked like mine, under the adoption, I was … curious. I found the village I came from… I could trace the patterns Eerlen had opened, from my memory, you see. And—”

“And?”

“They knew. My parent was sixteen. I think his sworn, the same age, was not very good from beginning. My parent was on the beach, mending the nets, alone, after everyone had gone home for the night.”

Selbur sighed. “Drahy liked them young. And Brinarians are small. I mean, it was before my time, but there are stories…”

“Yes,” I said, drily. “It certainly explains why I have an archmagician pattern, from a village without even a single small power… So, my parent caught. But he hadn’t called rape. No one knows why. He had no power, so he couldn’t realize he’d caught early. Perhaps he was scared his sworn would be upset? As I said, I don’t think it was a very good relationship. So he—” He shrugged. “Didn’t cry rape. Not even after it was obvious he had caught. Not even when I was born. If he’d cried rape and left me on the beach for the tide to take, no one would say anything. But he didn’t.

“I don’t think my parent’s sworn killed him, except by not helping him at all, and not letting him have more of the food while he was nursing. The whole village said he was very thin and weak at the end of the year of nursing. Then he got sick and died. My legal sire couldn’t expose me by then. But he could try to kill me if it looked like an accident. He tried harder after he swore again.” I was quiet a while. He was very close, separated only by the tray. “Eerlen never told me. He never asked me if I’d seen my own pattern.” I sighed “But I don’t rightly blame my legal sire. And I am not sure I wish to pass the legacy on.”

Selbur’s hand grasped my shoulder and squeezed hard. “Speaking of rats, Archmouse, you’re badly infested. We are all descended from rapists. Maybe not as close, but all of us are. And that is something none of the gossip says about you. Unattainable, yes. Rapist, no.”

“Yes, but—”

He took a slice of cheese, brought it to my lips, popped it in. I had no choice but to chew.

“Archmouse,” he said, very seriously. “Someone is going to keep feeding you cheese until you’re so confused you let him drag you off and tumble you.”

“Someone,” I said, in a grumble. “Thinks very highly of his cheese.”

He laughed. “Well, it’s Calenir, you know? I use the best for my seduction attempts.”

“Does that always work?”

“I don’t know. It’s the first time I’m trying it. But I think with persistence, it might.”

As much as I wanted to hold on to my fears, my isolation, my sense of owing both to the parent I didn’t remember, as I looked at Selbur’s little cat face, the challenge in his eyes, I started to suspect he might just be right.

Good story. More, please.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So am I crazy or…

…Is Book One an exploration of the masculine side of the hermaphroditic society, and Book Two delves into the feminine side? (Trying to leave out spoilers.)

LikeLike

No. Not really. They tend to be both, with both feet at the same time.

This is in the middle, between books.

Book 2 though does have Skip’s mom as one of the voices, which is hilarious because of how she views them.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Here’s the thing: the problem with sex in stories is both the irredeemably vulgar who cannot stop playing with feces, and those who find crossing boundaries itself titillating, rather than in-boundary sexy-funtimes.

That latter gets confused, because a natural part of sex is based on difference, and the novelty of the Other. (Vive la difference!)

Unfortunately the current civilization is irretrievably morally and …educationally? retarded.

So a mere lack of the former, while a godsend in not helping to build even more of the sexual and moral boundary-crossers, is not itself a useful marker for story-tellers like Mrs. Hoyt. She’s perfectly capable of expressing the universal humor that Brother Ass provides, without needing to paint with poop.

Our problem is the ones who write books like Big Wig, sweet and fluffy and pretty as cotton candy, to sell drag and sexual confusion to 1st-graders. Propaganda is the death of craftsmanship, but we’ve been marinating in neo-liberal and Marxist lies for so long, honest artists don’t perceive the poison pill.

It’s giving me headaches.

Get well soon, Mrs Hoyt, and may time, and a Holy peace heal your heart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Should never have sex in stories. Much more comfortable having sex in bed. And you don’t get the pages stuck to your butt either.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And paper cuts are dangerous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

/shudder

When I think of how much blood I left on file cabinets of paper records in the military I’m just glad I didn’t lose it all at once.

LikeLiked by 2 people

😅

LikeLike

It would be interesting to have these “side stories” available in the Kindle store.

Of course, they would need editing to match the Main Story, but we know how much authors loving editing. [Big Crazy Grin]

LikeLike

I’ve seen a few authors do that. Where the side story was a bear, not the main story protagonists.

LikeLike

Yes. I have a growing corpus of them, so maybe eventually.

LikeLike

This was a ginger with a spear. That was a blond with a high-tech pistol. The Other was a mighty, cunning and cruel beast who shrugged off both spears and blaster bolts; and was determined to have This and That for dinner!

Feeling a bit fey this morning. Leftovers from weird dreams of sliding down a road of chocolate pistachio and cookie dough ice cream in an empty ice cream container. Yeah, I have no idea either.

LikeLike

This, I think, is one of the things I love most about your books – these little scenes of romance and seduction. I mean, the characters and the worldbuilding and the story (oh my) are more than enough to guarantee I’ll buy anything you write, but this? You put most romance writers to shame, and there hasn’t even been a kiss!

LikeLiked by 1 person

THANK YOU.

My close in fans/first readers said that this proves Nikre is a girl. He can be fascinated with a piece of cheese…. Head>desk

LikeLike

Well, there is that meme about fascinating women with cheese. XD

LikeLike

yes. I had to go look to find it…

LikeLike

That meme was the first thing I thought of.

Which does kind of prove the trope…

The other thing that strikes me is how the extended family structure reads like the aftermath of multiple no-fault divorces. They’re co-parenting and not at each other’s throats, but the sheer amount of time and energy they’re having to expend on keeping all the social dynamics from exploding is absurdly high.

It’s no wonder they’re still barbarians: they have to spend all their time and energy on this, rather than any number of productive things.

And that’s pretty much how it really works. It’s just such an incredible waste.

LikeLiked by 3 people

They’re trying to LEARN family, but it’s not… easy. And even without divorces, most die really young

LikeLiked by 2 people

Agree.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This, That, and the Otter? Shifter crossover?

(grin)

LikeLike

Just saw Trump’s real-life meme on the White House wall, where the previous occupant is represented by a picture of a…robotic signature making device. 😄

Naturally, Democrats and their media lackeys are having a huge hissy fit.

I think the most appropriate picture for posterity would be Biden, not looking at the camera but staring blankly off into the distance with a vacant expression.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regarding the “breasts” aspect, we are unusual among mammals in having them. Other primates nurse young without having prominent mammaries the rest of their lives.

Just a sidebar for those who never considered the matter–

LikeLiked by 2 people

trust me, 14 year old me considered ALL MATTERS. I was a very lonely and bored child….

LikeLiked by 1 person

How does their time compare to ours? Is a 2 year old physically 2 by Earth standards? I assume their time cycle (day/year) is shorter than ours or a six year old would be too old to play with a two year old.

(Sorry-not-sorry)

LikeLike

yes. They catch up by about 3.

And no. days and years are pretty equivalent. Some kids are patient.

But the difference between them is three years. Oh, Kahre? Kahre is just a natural sweetheart.

LikeLike

As a mother of seven kids, at one point having four that were six and under, I can assure you that unless they are socially prevented from doing so, six year olds absolutely do play with two year olds, especially if they’re siblings, but 100% not restricted to that.

We’ve got a seven year old neighbor girl who downright pouts if she doesn’t get to play with our three year old, and I’ve watched boys bloom in getting to be the “big kid” to kids even younger than that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I still adore the Archmouse.

LikeLike

He’s so understated and so scary when he needs to be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I liked Ursula Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness although I was disturbed by it. Deserved the Hugo and Nebula.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is the lack of a print omnibus a factor of time, or is there some other constraints that mean Nope, never?

LikeLike

It will be 900 pages! so it’s a no, never. Because the binding wouldn’t hold, and —

LikeLike

Ah! Same reason as LOTR! (Length changing with technology.)

LikeLike

So publish it in multiple volumes and call it the Encyclopedia Hoytannica. 😇

LikeLike

Isn’t that what she’s doing? 😛

LikeLike

No. It’s only three volumes, and it’s not an encyclopedia.

LikeLike

Not now….

LikeLike

No, I mean, it’s fiction.

LikeLike

And HOPEFULLY fun.

LikeLike

Oh, always. And yes, I know you aren’t intending an encyclopedia.

LikeLike

I’m not speaking for Sarah on this, but I rather suspect the main factor is Amazon’s limitations with making paperbacks. Anything much over 100k words in paper tends to have the binding fall apart with minimal usage. No Man’s Land is north of 250k. So for a decent print edition that won’t anger fans by falling apart on first reading, Sarah would have to research independent printers and binders, find one she judged acceptable or better, make a separate deal with them, and… she’s got books to write.

LikeLike

Even more so for hard covers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I got books to write and more importantly I don’t have the money to invest thousands of dollars upfront.

LikeLiked by 1 person