(Like the Nidiot I am I scheduled this…. and forgot to flip pm to am. And for this I stayed up till midnight actually two am. Which means I carefully changed am to PM because…. Yeah. There’s a proud tribe of Nidiots and I’m their chief….. Sigh.)

For those of you who just dropped (from outer space!) in here, this is what I’m doing and why.

Yes, we did a double reverse and went back to this book, since one of you (Thank you Uncle Lar) sent me a copy. I refused to buy one because they run upwards of $30. And I’m cheap.

Anyway, for those not wanting to go through all of it, I’ve been reading myself back to my origins in science fiction, or what I read in science fiction. Until I was about 12 or 13 there was only one collection (after that there were others, often of Brazilian imprints. I remember fondly the blue-paper imprint that was designed for “night reading.” Fondly because, as advertised, it didn’t reflect the glare of the bedside lamp.)

For those wondering about only one imprint of science fiction, remember that there, as here, science fiction is a minority taste and when I was growing up Portugal had barely 10 million people. So, counting only those who read for pleasure, and only those who read science fiction… it was a very small readership. The side effect of this is that they did from the beginning what companies in the US only started doing in the oughts: print to the net. Which meant if you wanted to grab a book, you had to be there in time to pick up one of the limited copies. This led to lines on the day of the releases of the people everyone read. Sometimes books hung around in spinner racks in less travelled locales — I scored Glory Road (and other books I don’t remember) — in a small village we were traveling through. It was in the tobacconists. Why I don’t know, since in the big city any Heinlein sold out in mere hours.

Anyway, since I came on the scene a long time after the series started publishing, I missed a lot of the early ones, though I did find them afterwards in weird ways, like when I scored a box of old sf books by helping someone move.

Anyway, all this to say: I’d never read this book. In fact, until you guys told me I didn’t realize that David French was Isaac Asimov.

So, before we dive into this, let me say Asimov was never one of my favorites. I found him generally competent, and he wasn’t on my list of “I’ll read this under protest” — there weren’t enough books available that I could say I wouldn’t read a book — but he also didn’t light up my day. I can’t tell you why, even. This is a highly individual thing and his stories just didn’t interest me as much or stay with me. I did enjoy his short stories more than his novels and remember enjoying the puzzle science fiction mysteries.

Anyway, that out of the way and with the understanding he wasn’t one of my favorites, let’s plunge in.

If you need to refresh your memory on who Isaac Asimov was, go here.

The short version:

Isaac Asimov was born on January 2, 1920, in Petrovichi, Russia. He immigrated to the United States with his family in 1923, settling in Brooklyn, New York. His parents were Orthodox Jews, and he was the oldest of three children. Asimov graduated from Columbia University, earning a Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1948.

Asimov was a prolific writer, authoring or editing over 500 books. He is best known for his contributions to science fiction, particularly the Foundation series and the Robot series. His first published story, “Marooned off Vesta,” appeared in 1939. He also wrote extensively in popular science, making complex topics accessible to the general public.

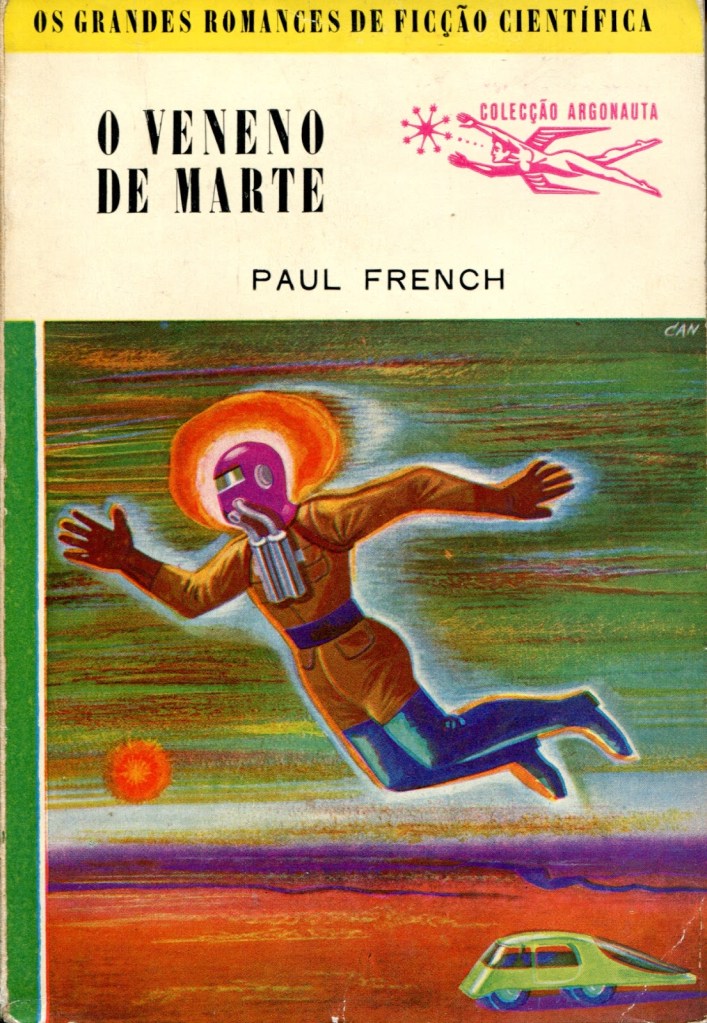

Anyway, this book published in Portuguese as O Veneno de Marte (The Poison from Mars) was published in America for the first time in January 1952. (It was published in Portugal in 1954 which is very fast and perhaps relevant. The taste of the people selecting these books were WEIRD even aside from their mad pash for French and obscure British books. Put a pin in this.)

The story starts with David Starr newly admitted to the council of science. (In all the human worlds, there’s a Council of Science which is … never mind. An interesting concept.) He was raised by two of the scientists in it, because his mother and father were killed when their ship was boarded by the pirates from the asteroids.

(Here let me insert that perhaps it’s not an accident that the rest of us consider the asteroids the symbolic bastions of freedom, but Asimov put the pirates and evil doers there.)

Anyway, David Starr is in a restaurant when someone dies of poisoning. There have been a lot of these poisonings and they all originate with products from Mars. The Council of Science sends him to find the origin of the poison in Mars.

There follows an unlikely set of adventures…

I think I should say that part of the problem I had with reading the book is that he seems to spend a lot of time tripping over what would be mundane stuff. Like, I really don’t need to hear about the force field tables in detail even once, much less repeatedly, while we’re dealing with someone who just died of poisoning, unexpectedly. I don’t know. It’s a matter of taste, but maybe this is part of what bothered me.

Another thing that bothered me was that though Mars is supposed to be “arm country” there isn’t much in the way of reality to the “farms.”

Perhaps Asimov simply hadn’t spent long enough in farms? I don’t know.

Anyway, while escaping an attempt on his life, David Starr ends up in a cave where he meets the Martians, who became… Well, it’s hard to tell? Either beings of the ultraviolet/energy or mind-beings, who live in caves under the surface and have absolutely no stake in what is happening on the surface, let alone in other worlds. They give him a…. scientifically cloaked magical invisibility device. (Look, I feel better about the science in No Man’s Land, suddenly.)

With the help of this, he solves the mystery of who is putting poison in the food to Earth.

I want to take a break here to note that the reason he’s called Space Ranger is not, as you might expect, because he joins a force of Space Rangers. Oh, no. It’s because one of the Martians names him “Space Ranger” because he ranges over space. Head>desk.

So, to return to that pin in the beginning: I find it weird that the people curating the publishing line chose David Starr over … Red Planet.

Though perhaps it makes sense since Red Planet is the American revolution turned into Science Fiction for kids and that might not have resonated with normal Portuguese people?

Anyway, this is relevant because when I was reading the book, it struck me as condensed, kind of floating over the top Red Planet fanfic. It was in fact published 2 years after.

Here I must insert that I don’t think Isaac Asimov did anything wrong. Look, ideas aren’t copyrighteable, and the story is not even the same. Not really. Except insofar as young spunky kid gets stranded in Mars and has to spend a night, and gets through it by strange means.

It’s more I feel like he read Red Planet and thought “I can do this better” and then wrote David Starr Space Ranger. Which… to my mind isn’t better, but that is obviously a matter of taste, and I’m sure there are people who prefer this book to Red Planet.

And it’s okay, because I feel like Heinlein read David Starr’s history and then decided to write it better for the character in Citizen of the Galaxy.

Anyway, on the salient point of the book: it was okay. It certainly wasn’t painful to read like the French one. Unfortunately it also failed to rock my world. I mean, it wasn’t bad, precisely. It just didn’t rock my world.

Anyway, um… if you decide to read David Starr Space Ranger, it’s okay. (It’s probably more worth the money in Audio, tbf.) It’s not like I want my time back from reading it. And I’m certainly in no position, being who and what I am to throw stones at a legend of science fiction.

It’s just I have a feeling our personalities don’t mesh, and what he was fascinated by (Council of Science. Pfui.) leaves me indifferent.

Oh, for the record, I think I would have liked this book much better if I’d read it when I was much younger and that might be part of the problem. I think he was going for a YA feel, and few YAs play well past their intended target.

One point of interest is that in this story, there was life on Mars before humans, of course, and there still is. Spores and bacteria and the like. And I practically flinched when Asimov’s people blithely talk about this not mattering at all, as they set about essentially terraforming Mars piecemeal to grow Earth food.

It is a mark of how much we’ve changed over the decades, that even I flinched from that and thought “well, that’s wrong” while Asimov, who — were he alive — would be still very much on the left and probably claiming the right of every microbe to avoid “colonialism” at the time was happily envisioning Earth life driving this other, inferior life to extinction. (Another point there being that the Council of Science isn’t even vaguely excited about thiis potentially completely different life and what they can learn from it.)

I don’t know. Perhaps I’m reading too much into all of this, but what went through my mind was “Well, yes, the left was all for colonialism and the extinction of any aliens that were in our way, until the USSR started to obviously fail, denying their ultimate ideal. And then slowly they changed their view and put on the skin of environmentalism over the same old tired Marxism.”

Note I’m not even accusing Asimov of this, just noting that this might be the mechanism through which our culture changed, and through which the left came to believe a bunch of quasi-religious ideas (some nonsense. Though I find that if there is life with a different origin than ours it would definitely be big scientific news and worth of study, duh) that coalesced in an attempt to find another vehicle for the socialism/communism that had failed as “scientific governance.””

In any case, the left today sure ain’t like the left back then. Not even the “scientific left.”

Which is why things like a Council of Science, centralizing such decisions, is a bad, bad idea. Because scientists are still human and emotionally susceptible to their peer group’s culture and decisions.

The best science is distributed science, where mavericks and Odds can find the things that “Official” science laughs at, and which often prove to be true after all.

So, next week!

That is From What Far Star by Bryan Berry.

A friend secured me a copy, as it doesn’t seem to be available anywhere, except used and pricey in print from Amazon. (Keep in mind that the Brian Berry listed on Amazon is not actually the same person. I don’t know who he is.)

For some reason clicking on his name there is no link to these books, but a search for his name brings up other used ones.

Anyway, I’ll try to do that for next Tuesday. Sorry this one took so long. A lot of things got in the way, mostly stupid things like really bad sleep. Which has also been getting in the way of doing Witch’s Daughter. I hope I can tomorrow. I’m “this” close to the end.

What might explain our mutual lack of enthusiasm for Asimov’s fiction is that he wrote mostly idea stories. Nightfall, for instance, is a brilliant idea told in almost nothing but exposition. The characters could be anybody. Likewise many of his robot stories neglected the characters to focus on his ideas. No surprise that he also wrote mysteries which tend to also be idea stories. For me, where he shined was in his non-fiction. He could make science and history extraordinarily entertaining.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Nightfall” is notable for being turned into possibly the worst movie ever made. Maybe because it was mostly exposition, but it was bad. Not fun-bad, like “Plan 9 From Outer Space.” Just bad. It’s the only time in my life that I ever walked out of a movie and demanded my money back.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I pity the poor screenwriter who was asked to turn Nightfall into a movie script. It just doesn’t translate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s probably an approach that would work, if one were clever and determined enough. But, you know, Hollywood.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The characters are probably why he worked better as a short story writer than as a novelist. He’s probably best known for “I’ Robot”, and the first three Foundation books. The former is a short story collection. The latter opens with short stories, until it transitions to novellas when the Mule arrives.

All four books are full of shorter than novel stories written at a time when books were much shorter than they are now. And until the Mule arrives, all of them deal with either robots acting oddly due to their rules, or basic human self-interest by the masses helping the Foundation survive another crises.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Idea stories” can be quite good. But they need to be short. Flogging the “idea” into a novel length exposition turns it into a slog for the reader. (As happened when Nightfall was expanded into a novel. That turned it into a rather mediocre post-apocalyptic piece of fiction.)

LikeLiked by 3 people

The mystery he did that sort of worked for characters was Murder at the ABA. OTOH, the MC seems to have been modeled closely on Harlan Ellison, and Asimov had a bit part in his own book. On the gripping hand, character growth was somewhere between glacial and nonexistent. Yet another book that I no longer have (I still have Nightfall & Other Stories, plus The Complete* Robot. The Gods Themselves almost made the cut, but, nope.

(*) It says “complete”, but only in the sense that it captured the short stories, not the two novels done by that time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of Asimov’s short stories has someone meeting “Isaac Asimov” at an SF convention, and deciding he was an egocentric jerk and a jackass.

When I saw Schwarzenegger’s “Jack Slade” character meet “Arnold Scharzenegger” in ‘Last Action Hero’ I was reminded of that short story.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Nightfall was a gimmick short story. Then a slow novella. And then a boring novel. And I think his premise that a fairly advanced civilization would collapse just because it got dark for a few hours was seriously flawed to start with.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Seriously flawed but a fun idea to play with–in a short story. I also questioned the mechanics of a system with, IIRC, six suns.

LikeLike

Ah, but if humans aren’t infinitely malleable, how can you mold them into good Utopians?

LikeLike

never liked Asimov. Hated Foundation. Don’t like the futurians in general much. It was only much later when I really came to terms with Marxism that I realized why. Scientific Socialism anyone? For our own good of course.

Paul Krugman remarked once that he wanted to be Harry Seldon when he grew up. I was much more attracted to the Mule, though not very much. The only business I wanted to mind was, and is, my own.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Given that so many of Krugman’s predictions and pronouncements fall flat on their faces, it’s probably as well he’s not actually Hari Seldon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hold a special loathing for Krugman. Not sure how, but even among a sea of self-important knaves and arrant idiots in the progressive milieu, somehow he topped them all. It’s not surprising at all that he’d want to be Hari Seldon. (shudder) I guess if being an “expert” opinion columnist for the communist paper of record was the most damaging thing that economic imbecile could manage, we should all be grateful.

LikeLike

Decades ago, I read the David Star novels (and lost my copies), but I had to chuckle about the “Science Council”.

Back when I was reading comics, I encountered both Superboy and the Legion Of Super-Heroes. The Legion was a super-hero team of the 30th/31st century and worked with an organization called the “Science Police”.

I guess authors of that time thought adding “Science” to an organization’s name made the organization “special”. Although I got to wonder the meaning of “special”. [Crazy Grin]

LikeLike

I guess that it wasn’t lost.

LikeLike

it was just distracted by something shiny over there —>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Lost my comment.

LikeLike

Isaac used to come down to this small convention I volunteered for in Lancaster PA. (Where I’m from, to be clear. I was a ‘farm boy’ who would happily ride 8 or more miles into town to get books from the library during summer. Went through the libraries of the three closest towns.) So I got to meet him in person, a LOT. He liked our con because he could take the train to it, and we fed him very well, of food he enjoyed. Young ladies would ask him to sign their chest and he would happily comply. Naturally THAT is what got on the news…

In any case, from what I observed, yes, he was obviously a city boy, and that city being New York City, he was stewed in liberalism when it was already morphing into ‘progressivism’. Mind you, he hadn’t totally lost his mind like so many others did later, but his ASSUMPTIONS had that bias, and it was sometimes laughably obvious. He attended room parties and filk sings. His singing was a hoot. But the first time he made some statement that was so laughably implausible, in a tone that told you he actually BELIEVED it, I was totally floored. Because, yes, Isaac was one of my icons, or literary heroes. Not as high as Heinlein, who I never got to meet, or Niven and Pournelle, who I did. But here he was (and the second time he came, he remembered me By Name, which also completely floored me!) doing something that blatantly revealed his ‘feet of clay’. So he was my first personal Hero that flung himself off the pedestal I thought he stood on. It was practically traumatic. As is often pointed out here, you can have many degrees, and be brilliant in many fields, and still be totally STUPID about certain things. I was still relatively young and naïve, so that was the beginning of THAT awakening.

And, yes, that began to explain for me why his stories sometimes had the weirdest ideas about the future. He thought that stuff was actually working in NYC, perhaps because all his friends wanted it to be true so very hard. Alas, even when it has become PAINFULLY obvious it HASN’T been working, so many STILL want to believe it does.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dare I ask what he said?

LikeLike

I no longer remember the specific statement, though I have the vague remembrance it had something to do with how schools should be run. And while I hadn’t been out of high school by quite ten years at that point (6, maybe?) it was so clearly NOT based on reality I was amazed. I couldn’t even square it with how school MIGHT have been when HE was a boy, but, hey, New York City, who knew?

LikeLike

From what he mentioned in one of his autobiographies, extremely regimented. He went to a school that didn’t even have a name, just “PS 182”. Which I assume meant “Public School 182.”

That sort of thing was common in Communist countries, but that’s the only case I know of in America, though some other big cities may have done the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seen references to “PS [whatever number]” in various stories from an early 20th-century setting, so I assume it was a big-city thing.

LikeLike

The Science Council would be composed of ‘scientists’ like Fauxi. Disagree with them and you’re ‘Rejecting Science!!’

LikeLiked by 3 people

THIS.

LikeLike

…and ‘Doctor’ Jill. And other credentialed nincompoops.

I recently read a short bio of Frederick Lindemann. He was the youngest of the physicists invited to the first Solvay Conference in 1911; considered to be a peer of Einstein, Rutherford, Curie, Planck, and the other attendees. But he moved from physics to politics, picking up some nutball eugenics and Fabian ideas on the way.

Like I’ve often pointed out to people, “smart” and dumbass” are different scales, not opposite ends of the same scale.

LikeLike

Yep, the Science Council were “Special”! 🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣

LikeLiked by 1 person

The reason that Asimov didn’t know anything about farming, despite having an advance degree in biochemisty, was that he was raised in NYC and stayed a metro-boy his entire life.

I’ve read much of his fiction, some of his non-fiction including his two volume autobiography, but none of it ever warranted a second read.

Like a previous poster said, he was an idea man, but almost all of his characters and prose are dry, generic and forgettable. An LLM running on a 2 MHz Z80 machine does a much better job.

In retrospect, he garnered his fame by being early in the field and being super prolific with a typewriter.

And as he got older and demanded respect from younger fen, his ego become larger than his total life word count. Conventions uninvited him due to his behavior. Being a jerk was measured in micro-Asimovs.

That’s without mentioning what a waste of oxygen his son turned out to be.

LikeLike

I heard a funny story a long time ago. Mrs. Asimov was taking a college class and the professor found out who she was.

“You’re Isaac Asimov’s mother? No wonder you write so well!”

[frosty glare] “You mean, no wonder he writes so well.” 😁

LikeLiked by 4 people

I never got much into Asimov’s fiction, certainly not enough to re-read over and over again.

For instance, Nightfall, once you’ve read it, you “got the joke” and it’s not worth re-reading. Unlike say stories by Heinlein, Pournelle, Drake… I want to “spend time” with those characters again even if I know the outcome.

I re-read the Foundation books again recently because I hadn’t read them since High School and really could not remember much about them. That probably fulfills my lifetime quota.

I did like his non-fiction science stuff. One of his books on chemistry helped me understand what I was being taught in High School Chem II a bit better.

I think Asimov was much more consequential as a personality in Science Fiction than as an actual writer.

LikeLike

Was that ‘The Chemicals Of Life’? I read that too. Very informative.

LikeLike

I saw it in the local used book store, and have been kicking myself ever since for not picking it up – the one he wrote on the coming ice age.

Which book has apparently been completely suppressed…

LikeLike

Don’t recall now. That would have been in the late 70s.

LikeLike

I bought the later Robot and Foundation novels when they came out in hardback (bought a lot of SF at that time; we had a really good independent bookstore near work and they’d hoover a chunk of my paycheck), but beyond skimming one or two (<i>Robots and Foundation</i>, and perhaps <i>Robots of Dawn</i>), I think I never got the round tuit to read them.

Eventually, I figured out to be a bit more discreet in purchasing. Slightly. Kindle purchases don’t count. [grin] Being closer to MGC and N Texas Troublemaker authors makes that a better bet.

LikeLike

His book on The Brain was the first LARGE textbook I happily read voluntarily. He came up with so many amusing ‘subject adjacent’ stories to explain and illuminate things! I got the feeling many of them were from his own child hood, told to him by people he likely respected.

LikeLike

Asimov could write an article about making mud pies, and he would start with the atomic structures of silicon and carbon, how they interacted with dihydrogen monoxide, and then he would barely be started.

What I liked about his science articles was he almost always gave you a solid history of “how they got there” instead of “the atomic weight of oxygen is 16.”

Even the ones that are now outdated are still useful for their background information. And Asimov always hammered in that science was a *process*, and that new discoveries kept refining ideas.

LikeLike

Yes – he always assumed his readers were intelligent, but lacking in background on the topic at hand.

LikeLike

Actually, the two books by Isaac Asimov that I’ve re-read the most aren’t even his fiction, but are “Understanding Physics: Light, Magnetism, and Electricity”, and “Understanding Physics: The Electron, Proton, and Neutron.”

LikeLike

I’m rather fond of his book on the Shakespearean plays. There are multiple good observations in there, including how to make sure that Taming of the Shrew is not misogynistic (it’s all in presentation, and when I saw OSF perform it, they basically played it out like he’d said. Petruchio isn’t trying to beat Kate into submission; he’s trying to break down the barriers she’s put up against believing that she can be loved. Hardly surprising that she has those, considering all those guys who talked nice to her just to get at her beautiful younger sister…)

LikeLike

Do micro-Asimovs map onto milli-Garns?

I was saddened to hear of his passing, but I don’t re-read his stuff.

LikeLike

On a long motorcycle trip I stopped for the night at a motel in Amarillo. There was a stack of newspapers on the desk, with Asimov’s death on the front page.

LikeLike

Agree with most of this. Surprised nobody mentioned, “The Ugly Little Boy.”

In case you don’t remember: the little boy is a Neanderthal child brought from the past for study. One of Isaac’s patented lonely, repressed (but highly educated) spinsters is his main (only?) human contact.

The boy is kept in a room which is surrounded by a temporal field which keeps him in our time. If the field is turned off, he will be returned to his own time. Where, since there’s no way to put him back exactly when/where they found him, is a probable death sentence. And the other scientists involved in the study are indicating they’ve learned all they can from him.

So when the spinster can’t persuade them to keep the child, she makes an irrevocable choice…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes. That’s one of Asimov’s best stories, because it actually has a human being in it that you care about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He either said it was his favorite or one of his top three, I can’t remember which.

LikeLike

The story he thought the best was The Last Question. Which definitely has its points.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Silverberg novelized that story in 1992, same year Asimov died.

It appears that in 1977 there was a movie based on the short story.

LikeLike

The Brazen Locked Room is also good, though just a bit thin. (Perhaps the issue is most clearly indicated in that that is the editor’s title; he thought Gimmicks Three was a good title, even though it broke the fourth wall.)

LikeLike

One reason Asimov never resonated as much with me as some other authors was his books all seemed very claustrophilic to me. Read long enough and I’d feel the walls closing in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the Caves of Steel, he had the people of an overpopulated Earth live crowded into giant Cities. Someone complimented him on the dystopian hellscape he created, and he didn’t know what they were talking about

LikeLiked by 1 person

That. Yes. I’d go crazy!

LikeLike

Niven and Pournelle did it better, but without the population bombing. Oath of Fealty?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Everybody ate food made out of yeast.

I know people who are allergic to yeast.

Guess they wouldn’t be around…

LikeLiked by 1 person

At least he didn’t have them eating bugs.

LikeLike

The Foundation universe does that for me. All those bland, unremarkable planets (except Trantor, a city, of course) and the Seldon Plan laying out their future for millennia to come. In reality, I get the feeling unpredictable natural disasters (a supernova a few centuries early, for instance) would throw the Plan off pretty quickly.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Asimov actually understood some of his flaws as a writer. He shows this in his short story “Gold”.

LikeLike

Willing to guess that the “Space Ranger” part was handed to Asimov by his publisher and he didn’t want to do anything, you know, low-brow, so he worked it into the novel as best he could.

As to the Science Council, I’m pretty sure Krypton had one of those. How did that work out for them?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It didn’t which is why Kal-El (Clark Kent) is one of the Last of the Kryptonians. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not quite true. There’s Kara, General Zod, the entire population of Kandor….

LikeLike

The Great Escalation Problem.

It’s like Doctor Who. Having one Dalek escape the devastation was one thing. Having them revealed as having survived as a race undercut everything.

LikeLike

I said “one of the last of the Kryptonians”.

IE Meaning that there were other living Kryptonians.

LikeLike

Also in the interest of hyper-pedantic accuracy, the character’s surname is “Starr”.

(Yes, yes, I know, typos, typos, typoes . . .)

LikeLike

It was TWO IN THE MORNING.

LikeLike

Even I managed to sleep past 2AM. Coherency does not come quickly at that hour.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My wife was a life-long mystery lover who regularly read Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. She said she enjoyed Asimov’s Black Widowers mystery stories, but I’ve never read them. They sound like a perfect venue for exploring ideas without bothering with character development.

LikeLike

Asimov was much better as a short story writer than a novelist. When writing a book he seemed to feel that he had to stretch things out with filler and as a result his characters talked too much. This got especially bad in his later books.

His best science fiction book , in my opinion was The End of Eternity, perhaps because it had an un-Asimovian theme. In general Asimov liked the idea of a hidden elite planning out societies, think Seldon and the Second Foundation. In The End of Eternity he argued against the idea, with the character fighting the time changing Eternals pointing out that beside the colossal hubris, such an elite will always prefer safety and stability over freedom and innovation.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree on short vs. long. Azimov had some great ideas that worked perfectly in short fiction. When he tried to build the theme into a novel … It didn’t work as well, in most (99%) cases. The humor in some of his short fiction never seems to make it into his longer works of fiction, either.

LikeLike

End of Eternity has an interesting background.

I once read what I think was a short story collection of his where he also included info on where he got some of the ideas for his stories. End of Eternity is an interesting one. Apparently he was flipping through an old periodical from the Inter-War period. The periodical had advertisements, and as was common at the time some of them included black and white pencil sketches as pictures for the advertisement. The picture in one of the ads clearly showed something connected to nuclear technology (I don’t remember what, off the top of my head), even though the ad was for something else. And in any case, nuclear technology wouldn’t be discussed in anything but scientific journals before World War 2. You wouldn’t find a picture of something connected to it in an advertisement in a random periodical.

He had stumbled across what seemed to be an unusual real-life anachronism.

He thought about it for a bit, and came up with the idea of a stranded time traveler using that ad to send a message to his fellows in the distant future so that they could come rescue him. And the short story ‘End of Eternity’ was the result.

The problem was, after the story was published, he had to admit that the name didn’t really match the plot. Eternity doesn’t end in the short story. It’s nearly destroyed, but manages to pull off a save. So he turned it into a full length novel.

I’ve read the short story, but haven’t read the novel. I could no doubt find it on Amazon these days. But back when I originally read all of that, Asimov’s back catalogue that wasn’t about robots or the Foundation was simply not on shelves. So I never read it.

On a completely unrelated note, back during the early ’90s, there was a very short RPG rulebook with two supplements called ‘Macho Women With Guns’. The game was more humor and parody than seriousness. One of the enemies in the published product was a being by the name of “Isaac Azathoth”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is available as a Kindle eBook.

LikeLike

There is also The Flying Sorcerers by Larry Niven and David Gerrold which is essentially a giant shaggy dog story to make a pun on Issac Asimov’s name. There is also some pretty hefty tuckerization of many of the Sci Fi authors such as Elcin (The small but loud and mighty god of thunder), Fineline the god of Engineering, and Rotenbair the god of Sheep.

As for Asimov’s writing I agree, he is best in the short form, especially in that now near extinct niche of “Idea Stories”. He was not very good at characterization, and particularly his women are cardboard except for a few instances (e.g. Susan Calvin from I Robot, and the lead female character in Foundation and Empire whose name escapes me) and even in those instances those characters read more like autistic men in drag. I did love his stuff as a kid with I, Robot being one of the first 3 true sci fi books I read (the other two being Ray Bradbury’s S is for Space and R is for Rocket all from the Junior high library).

I did get to hear Asimov talk at my Alma Mater (WPI) Circa 1980. He read as a really arrogant SOB. I and my apartment mates were thoroughly unimpressed with him and his talk, and we were all fanbois. And yes very much a City boy, and did not fly. I think he was in NYC at that time so Worcester was train/car trip (train to Boston, car out to Worcester, commuter rail existed but was REALLY beat up in the 80’s and the Worcester Station was a mess).

LikeLike

He had a phobia about flying. He knew it was irrational, but he had it.

LikeLike

Yes. The End of Eternity greatly adds to my respect for Asimov, because it shows him challenging the validity of one of his own ideas.

LikeLike

c4c

LikeLike

I really wonder what Asimov would have thought of the AI we have today? I’m sure his Robot series would have gone in rather strange directions. Even his Foundation books would have been strange if psychohistory were subjected to the random strangeness we see in AI results. By the way, the above picture is what an AI generated as the stereotypical woman from Maine. AI-Generated Women from All 50 U.S. States That’s no lobster I’ve ever seen, and considering her hands, I’d have to suspect she’s actually from Innsmouth, Massachusetts.

LikeLiked by 2 people

All I have to say is AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGGGGGGGGGGGGHHHHHHHH!

Also, AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAGGGGGGGGGGHHHHHHHHH!

LikeLike

You ain’t kidding. One hefty dose of nightmare fuel, right there.

LikeLike

Break out the Elder Signs, stat!

LikeLike

She looks like an undergraduate at Miskatonic University.

The fingers! The fingers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Last and First Men, his first published work of fiction (it’s not exactly a novel), Olaf Stapledon has Earth becoming uninhabitable, so the human race that lives there (something like the Fifth or Sixth Men) migrate to Venus. Venus’s oceans are inhabited by an intelligent race, but the human migrants just exterminate them, because they need the planet and can’t share it. I’ve read that dislike of this idea is part of what inspired C.S. Lewis to write Out of the Silent Planet, where the scientist villain advocates similar ideas to the angel who rules Mars. As it happens, Stapledon was a lifelong Marxist sympathizer; the last time I reread Last and First Men I noticed some rather unsubtle anticapitalist satire. The same kind of thing turns up in his pioneering superman novel Odd John, where the Homo superior teenagers have no hesitation in mind controlling the people of a remote Pacific Island into mass suicide to make room for their colony; they assure the narrator that this is just like human beings killing off apes or monkeys to clear space for a farm.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Stapeldon was ambivalent about Communism; it appealed to him, yet he knew it was turning ugly. He did see himself as an intellectually superior man and he possessed no trace of a sense of humor, though he understood such a thing existed.

I suspect Lewis put his analog in The Screw tape Letters; Screw tape tells Wormwood about his patient who nearly got away from him, until he showed him some mundane things and got his mind back off God.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s repugnant.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Meanwhile, Starship Flight 10 launched released all eight Starlink simulators. Looks very good, so far.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Flight 10 did everything it was supposed to, including orienting for a vertical landing before hitting thr ocean. Images are, of course, gorgeous.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been quite nervous about that – guess I dare to watch the replay now!

LikeLiked by 1 person

same.

LikeLike

Good to hear! Hopefully SpaceX can duplicate that in the future.

LikeLike

The amazing (well most amazing thing) to me is that they launch it from Texas and land it 2/3rds of the way around the world in the Indian Ocean somewhere west of Australia and manage to stick the landing probably not more than 100 meters from a camera bouy they had left there. And of course using Starlink so you can get data and live video from the Starship during reentry.

I think this is the last flight of V2 Starship. This one did pretty well although there were some oddities including some minor explosive event in the engine area and the rear fins got pretty beat up (though they held up for reentry, I was biting my nails there for a bit). They’ve got a ways to go for the lunar version as well as hitting test runs to mars in the 2026 Hohmann orbit window, but I suspect they’ll have a ball trying to hit those marks.

LikeLike

More than anything, his stuff reads like a reaction against the colorful, pulpy SF popular at the time. You certainly wouldn’t find anything as thrilling as smashing galaxies, like you would in Smith or Hamilton. No sir. Excitement is to be studiously avoided in the Asimoverse. If you find your pulse racing while reading his works, please consult your physician.

LikeLiked by 1 person

back in the day when there was more science than fiction, fun but campy years later

LikeLike

Lots of adults read YA. (That’s why the YA authors get pressured to make it less YA.)

LikeLike

… which kind of misses the point. Adult readers who read YA read YA because it’s not adult.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It exactly misses the point. Which is why trad is dying.

USAID going down could not have helped. Trad really was useful for launder bribes as “advances.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

This.

LikeLike

I’ve read most of Dan Wells’ and Scott Westerfeld’s YA books. Most have solid stories with a beginning, a middle, and an end, which isn’t a guaranteed thing nowadays, plots that make sense, and characters who aren’t crazy Woke. Other than the protagonists mostly being teenaged, they’re not the kind of “young adult” stuff they used to try to pass off as ‘age-appropriate books’ years ago.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I really like the Westerfield steampunk trilogy (starting with Leviathan.) Just the right amount of adventure and romance (old-style; only a little bit of romance two-people style.)

LikeLike

In his day, Asimov broke new ground with his robot stories. Before him, robots had almost always been “Frankenstein monsters” that got out of control and destroyed their creators. He wrote about robots that were useful and had limits built into them so that they wouldn’t run amuck.

The Foundation series was heavily influenced by Marxism (the idea that history is predictable, for one thing) but that’s hardly surprising. Asimov grew up in New York City at a time when the Communist Party was more respectable than it ever was before or after. Murray Rothbard told about how it was for him and his father, being the only “right-wingers” in a neighborhood otherwise full of Reds of various sorts. (Rothbard said that they were treated well, as a useful source of information—“what would right-wingers think about this?” Unlike modern liberals, a lot of those people did understand that they lived in a bubble, and wanted to know what people outside the bubble were thinking.) Not for nothing was the period roughly from 1929 to 1945 called “The Red Decade.” This was particularly strong among intellectual types and in academia, which was Asimov’s own milieu.

His “Black Widower” stories did well with characters because the characters were based on people he knew in a dinner club he belonged to called the Trap Door Spiders. He Tuckerized the whole lot of them.

LikeLike

For those like me who were confused when Sarah mentioned that Asimov is David French: as the image of the book cover shows, she meant Paul French. (It was 2 am, so be nice)

LikeLike

You are correct. It was 2 am and I was awake with spite and coffee….

LikeLike

I just re-read the first paragraph about scheduling and remembered scheduling a payment for a credit card a day early, I thought. Turns out I changed the day to December 31 on the calendar clickie thing but forgot to change the year to current year; so I scheduled the payment for the end of the next year. I asked the nice lady at the customer service number if I could get credit for trying and waive the late payment fee. She did.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Asimov, the little I’ve read by him, hits me the same way as it does most here. A little “meh”.

I read the “Lucky” Starr books because I got sick and my mom picked up some scifi books for me at the mall. One was the “asteroid pirates” one. I liked it quite a bit. Still do. I ended up getting all 6 – most with gorgeous Berkey covers – and liked most of them. As I got older it seemed to me that they were more like light teleplays than novels. Maybe an attempt at a “Rocky Jones, Space Ranger” type of TV show that didn’t happen. I should find out if I’m right… I read his autobiography but don’t remember if that idea is confirmed or not in there.

Anyway, I did my first “great purge” of books from my shelves a couple of years ago – up til then I’d kept 99.9% of the books I’ve bought since I was 8 years old – and the “Lucky” Starr ones survived and are still on my shelf. Dunno if they’ll survive the next one.

LikeLike

I’m lucky in that I have a donation source for all my purges. SF or fantasy I won’t read again? They’ll take it all, and possibly enjoy it more. I think it was six boxes last time, just from my husband going through “his” books. Well, there were a bunch of books signed to someone who had died a couple of decades back, but lucky me, these folk had *known* him too, so they could appreciate that as well.

No guilt getting rid of things when you know it’s going to an appreciative home.

LikeLike

I read a lot of Asimov growing up. A couple years ago I tried to read some of his works again, in particular, Caves of Steel. Barely made it through. It was extremely depressing: domed cities, people eating in assigned cafeterias, scarcity, everything highly controlled by the government. It was nearly as depressing as Silverberg’s “The World Inside.”

It is interesting that some science fiction writers of the time seemed to have so little faith in science to solve problems.

LikeLike

The “problem” they wanted solved by “science!” was self-interest based independent action.

“If everyone would just do what their betters told them….”

LikeLike

I loved Asimov in my early teens. By the time I hit my 30s I’d read his stuff and think, “Boy this is lame.” So there may be something to your not cottoning to him.

Mind there were other SF authors I read as a child and teen that I loved then and still love today: L. Sprague De Camp, Robert Heinlein, and H. Beam Piper especially. Poul Anderson’s stuff written in his crazy lefty phase in the late 1940s early 1950s was the only other stuff that went from great to lame as I aged, (Think the UNman stories.) But I still love his later stuff – Van Rijn and Dominic Flandry and on. No Truce With Kings is still as great to reread today as when it first came out.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I found Anderson’s early “crazy lefty” stories generally more readable than his later stuff, which I found mostly depressing. “Everything sucks and we’re all going to die” just doesn’t have a lot of entertainment value for me.

LikeLike

I was slightly off balance seeing “David Starr…”

Took a moment to realize the post was about the “Lucky Starr …” series of books that were among the very first SF that I read, starting around 11 years old.

Also began reading the Heinlein juveniles about the same time; I liked them a lot better, and they’ve held up a lot better since … um … 1961 or so for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

well, the title of the book in english is David Starr Space Ranger.

LikeLike

I understand. But.

The first one of the series that I read was “Lucky Starr and the Oceans of Venus”, then the later ones. When/if I got around to reading the actual first in the series, I guess I just sort of flew past the title thinking “another Lucky Starr book …”

I spent many Saturday afternoons in the Whittier, CA public library reading everything they had in YA SF and history and … Apparently no time to waste on niceties such as book covers beyond “Ooh! I haven’t read that one…”

Thinking back, Asimov was somewhere behind Heinlein, Norton, Simak, and de Camp in my preference lists. Although I did rather like the shorts that he wrote around that time for some tech company’s advertising campaign in Scientific American. (My grandmother got me subscriptions to that and Analog [it was printed in a larger format around then] to encourage me in studying science. I didn’t correct her misapprehension.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Larry Niven might not have been the first to make the asteroid-dwellers fiercely independent, but his Belters influenced a lot of later SF writers.

LikeLike

Asimov was raised in New York City and was an urbophile. He thought Boston was hicksville when he was teaching there.

I was probably nine or ten years old when I read “Caves of Steel” for the first time. His giant regimented Cities sounded like Hell on Earth to me. It wasn’t until I was re-reading it fifty years later that I realized Asimov actually thought the Cities were an optimum civilization. A very different worldview from, say, Heinlein or Simak, who were country boys by comparison.

As far as I’m concerned Asimov’s fiction was readable, but nothing I would specifically seek out. By comparison, his books on physics, chemistry, etc. were excellent. (as were those of Willy Ley and George Gamow, now mostly forgotten)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Asimov always had a difficult time imagining rural. The Naked Sun takes place on a planet that’s mostly automated farms, and a few humans, and it… reads like a city kid trying to imagine what automated farms are like, but the kid begins by thinking all that stuff is boring.

LikeLike

I did spend most of my day today at the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. But the Council of Science was apparently not in session.

NASEM shook a lot of things up internally this year. Even though they are technically independent, they get a lot of indirect Federal funds, and rumor has it the “new sheriff in town” wants to see more results aligning with Executive Branch priorities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just an observation, as a young teenager, I enjoyed the books of Andre Norton. Which I learned later in life was the pen name for Alice Mary Norton.

LikeLike

Er… we know?

LikeLike

We’ve made some progress. Women can publish science fiction without needing to hide behind pseudonyms. Yay. 🙂

LikeLike

People knew that Leigh Brackett was a woman long before then.

LikeLike

They always could. It just wasn’t “respectable” writing science fiction, you know? And women want to be respectable.

LikeLike

There was a generation taken in. Even I, however, belong to the generation that grew up thinking Andre was a girl’s name because the only Andre we knew of was Andre Norton.

LikeLike

Me, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What do you think of this one? Novella? Short story Profession by Isaac Asimov (1957) also called Education Day.

LikeLike