A snippet from 9 AD: The Crossing of the Rhine by Tom Kratman

9 A.D.: The Crossing of the Rhine, Copyright © 2025, Thomas Kratman

Dedication: For my friend, General Claudio Graziano, of Turin Italy, and, further, of Italy’s fine Alpine Troops. 22 November, 1953-17 June 2024

Chapter One

[W]ho would relinquish Asia, or Africa, or Italy, to repair to Germany, a region hideous and rude, under a rigorous climate, dismal to behold or to manure [to cultivate] unless the same were his native country?

— Tacitus

Northwest Germania, September 9th, 9 A.D.

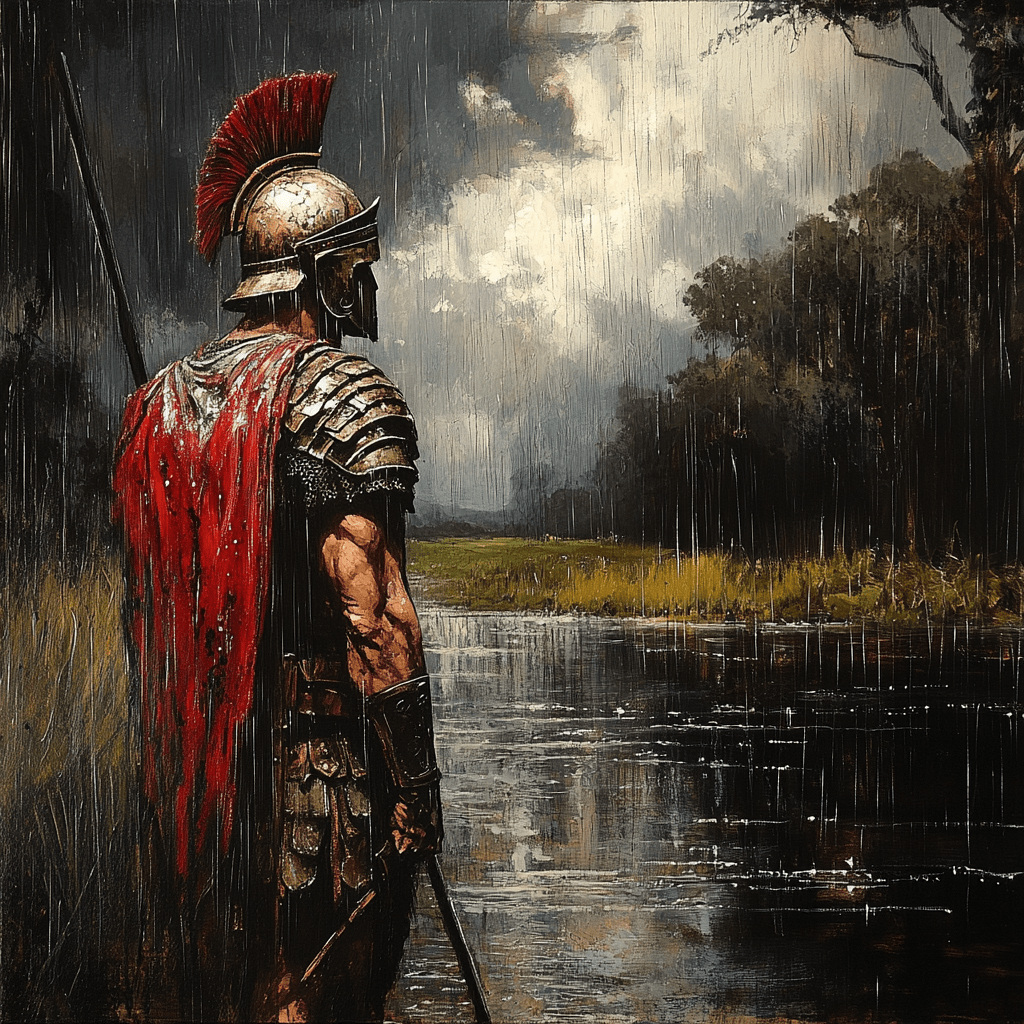

Rain poured from a leaden sky onto twenty thousand miserable, shivering soldiers of the Roman Empire. To add to the misery, a cold northwind swept around them, finding the holes in their cloaks and the chinks in their armor, chilling them to the bone. The forest around and above them did nothing to shield them from either wind or rain.

Two men, a junior officer and what later generations might have called a

“regimental sergeant major,” stood in the rain, trying their best to look unworried. The five or six thousand men with them might collapse if they saw fear on the faces of their remaining leadership.

“What was the name of that town, Top?” asked the officer. “The one on the Lupia River, about a week’s march east of the castrum at Vetera? I think it was two days’ march before we went into summer camp on the Visurgis. I’d been thinking I’d liked to have retired there, after my time with the legions was up and Lower Germany pacified and brought into the Empire.”

Military Tribune Gaius Pompeius Proculus’ face was ashen, though the centurion to whom the question had been addressed thought the boy was doing a commendable job of keeping the panic out of his voice and fear from his dark brown eyes. Which was good because, with the senior tribune butchered by the Germans, early on, the legate, if he was still somehow alive, stuck somewhere out there with Varus, and that newly worthless turd, Camp Prefect Ceionius, looking ready to bolt, command would like as not fall on the young tribune’s shoulders before nightfall.

Proculus was young, in his early twenties, and swarthy, like many Romans from the city, proper. And, though he now carried a shield courtesy of a dead or badly wounded legionary, he wore a very high-end gilded muscle cuirass, partially concealed by a fine quality, red-dyed sagum, or cloak. Repelled by the lanolin which had been left saturated in the wool, rainwater ran off in rivulets, gathering at the bottom seam to drip onto the ground in a heavy stream.

In his right hand Proculus carried an equally high-end short sword, ivory-gripped and from steel forged in Toledo, Spain, much like the blade of the one carried by the senior centurion he had addressed as “Top.” Atop and around his own head the tribune wore a crested officer’s helmet, below the muscle cuirass hung a kind of skirt made of strips of white-washed leather, reinforced with small metal plates.

“Forget that town, sir; it doesn’t exist,” answered the first spear centurion, the centurion in charge of the first century, of the first cohort, of the legion, removing his transverse-crested helmet from his reddish blond head to let the sweat evaporate. At over fifty-three years of age, his hair was shot with gray and had gray at the temples. “All that exists is that idiot Varus, dying back there with most of the Seventeenth and Nineteenth, and our own commander. And the impedimenta with the bulk of our tents and rations, of course. Oh, and the twenty-five or thirty thousand hairy, smelly barbarians in the process of killing them; they apparently exist, too.”

Primus Pilus Marcus Caelius Lemonius pointed with his chin to the east, whence came the sounds of battle – the clash of stone and iron on bronze and steel, the terrified neighing of horses and lowing of oxen, the screams and shrieks of wounded and dying men and men gone mad – clearly, even through the thick, confusing fog. Even at this range and even with the trees, the fog, and the sound-absorbing mud of the ground, it wasn’t hard to tell Latin from German. Nor, from the rising inflection and volume of the Germanic war chant, the barritus, to grasp that the Romans in the main group were losing. Badly.

But they haven’t given up the fight yet, thought Caelius. That would be a whole different sound.

Caelius scorned anything resembling a muscle cuirass. Instead, he wore a lorica hamata, a chainmail hauberk, as did most of the legionaries of the Eighteenth. A few of the newer men, those in the Second and Seventh cohorts, had those new-fangled things, the loricae made from face-hardened steel bands around the abdomen and over the shoulders, the whole assembly being held together by leather straps to which the bands were riveted.

The men who wore them never ceased their complaints about how beastly uncomfortable they were.

Caelius also wore a single greave, on his left, or forward, shin, adding a measure of protection where needed beyond what the scutum could provide. He’d bought a pair, but had found he didn’t need the one for his right leg and that using that one slowed him down more than he liked. He still kept it, for use on parade and such.

“Be our turn, too, soon enough.” Caelius looked around, outwardly sneering at the futile efforts of the men of the Eighteenth, along with the few hundred cavalry, two of the auxiliary cohorts – archers and slingers they were, in one case, and simple light troops, Germans who had taken the oath to the Emperor seriously and unto death, in the other. Flavus, the brother of the arch-traitor, Arminius, kept the cohort of German light troops well in hand, aided by an old sub-chieftain of his tribe, Agilulf.

On his own initiative, Marcus Caelius had pulled in the perimeter to form a camp for about six thousand men, which Legio XIIX might have chance to build and defend, from the initial one planned, for twenty thousand men and no small number of brats, tarts, and suttlers. Even so, progress, amidst all these trees with their tough and entangling roots, was slow and inadequate.

Not even the legion’s own small wagon train, the impedimenta, could add much to the defense, though it helped to strengthen the vulnerable corners a bit. And Marcus Caelius was pretty sure he didn’t entirely trust the German auxiliaries, Flavus and Agilulf or no.

“Even if we get so much as a half-assed camp built,” Caelius continued, “we’ve got maybe enough food for a week or ten days, on the men’s backs and in the wagons. So we’ll still have to try to break out. And there are too many of those shitty-assed Germans to have a hope of that. And, no, sir, there aren’t any legions close enough to march to our aid.”

“But,” countered the tribune, “Surely these barbarians will starve before we do. They’ve no logistic skill or foresight; barbarians never do.”

“I’m not so sure of that, sir,” replied Caelius. “In the fourth place, they’ve been learning from us. In the third place, they’ve been here for some days. Couldn’t have built that wall to the south that’s given us so much trouble all that quickly. Probably started stockpiling food here when Varus sent that treacherous bastard Arminius to prepare matters for our arrival on the Visurgis. And didn’t that son of a pitch prepare matters for our arrival? Maybe even before that. Maybe for the last couple of years; this ambush was planned. But in the second place, they couldn’t have known when we’d show up so, for something this important, probably brought enough for several weeks, at least. But in the first place…”

“Yes?” the tribune prodded.

“In the first place, they’re likely going to have captured all – most at least – of our food.”

“Fuck,” said the tribune.

“Fucked,” corrected the centurion.

While, outwardly Caelius might have sneered at the men’s efforts at building a camp, inwardly he was deeply proud that the men of his beloved Legio XIIX were still trying, hadn’t given in to the panic clutching at their vitals.

“Is there any—” Gaius’ words were cut off by the cry, picked up at one or two points of their irregular perimeter and echoed across the lines: “Here they come again!”

Men who had been digging in their armor dropped their picks, mattocks, and shovels, on the spot, retrieving their red-painted shields from where they’d been placed, stripping off the leather covers that protected them from the wet. Still others had gone forward to retrieve previously cast pila. These last now scampered back to their own lines, some with four or five heavy javelins in their hands and arms, some with as many as a dozen, and some with only one or two, the one or two shanks still stuck in German shields. Those men had also spent some of their time out in front of the lines usefully finishing off any wounded Germans who hadn’t been able to do a convincing job of playing dead. And some who had; this was called “making sure.”

The men who had retrieved the javelins hadn’t bothered taking back any that looked broken or bent; no time for that. They passed around what they’d brought back to their comrades. Some of those struggled to extract the still functional pila from the shields they’d pierced. Even with the encumbered ones, once freed, there wasn’t quite one pilum for each man.

“What was that, sir?” asked Caelius, putting his helmet back on and tying the chin cord.

“Nothing, Top.”

“Right. Sir, why don’t you stay here? I’m going to walk the perimeter. I also want to have a chat with the chiefs of the auxiliary cohorts and the senior centurions trying to organize the escapees and advanced parties from Seventeenth and Nineteenth into something like military formations.”

“Sure, thing, Top,” the tribune replied, though he was loathe to lose the first spear’s steadying company. Moreover, he always tried to be honest with himself; “Know thyself, that’s what Menandros, his tutor in philosophy, had tried to drum into his head. So Gaius Pompeius understood perfectly well that he lacked the first spear’s presence, charisma, and way with the men. To say nothing of battlefield insight. It’s one thing to have read about Nero Claudius Drusus’s campaigns in Germania, quite another to have been a part of them.

Gaius wasn’t stupid, he was pretty sure, so figured he’d learn these things eventually. But for now? Let the experienced non-com handle matters and take his advice when a decision was called for that required an officer.

Well, I would have learned those things, eventually, he thought. But I’m going to die here in an unmarked grave. Wait, who am I kidding? The Germans aren’t going to bury us; they’ll just leave us for the wolves and crows.

As Caelius turned to go, one of his freedmen, Thiaminus, also called Caelius, ran up and tugged at the sleeve of his tunic. “Sir, the Camp Prefect would like a word with you.”

“Where is the wretch, Thiaminus?”

The freedman – Caelius had freed both Thiaminus and his other servant, Privatus, largely because he didn’t think you could hope to trust an outright slave when the going got tough – made a subtle little gesture with his head, adding for emphasis, “He’s hiding in that thicket over there. Next to the legion’s eagle.”

“Of course he is,” Caelius agreed, genially. “What else would he be doing? Lead the way, Thiaminus; I may need a witness.”

Even as Caelius turned, a chorus of centurions ordered their men to “loose,” which led to a strong volley of pila, and a good deal of most satisfying and exemplary Germanic screaming. This was followed by the sounds, much closer than where the men with Varus were dying hard, of clashing metal and stone.

The way led past the legion’s small battery of scorpions, small torsion driven artillery, capable, under ideal conditions, of throwing a heavy bolt with quite respectable accuracy a distance of four hundred and fifty or so yards. Sadly, in Germany’s miserably wet climate, accuracy and range both fell off dramatically.

Even as Caelius arrived at the battery several twangs sounded as the scorpions shot their bolts. To the first spear, the sounds seemed off.

“Not that it makes much difference, Top, the endless rain,” said the chief of the scorpions, a senior centurion named Quintus Junius Fulvius, from Caelius’ own cohort. “Beyond that this damp has the skeins all floppy and as loose as an old whore’s vagina, I’m just about out of ammunition. I’ve got some of the boys out cutting some wood but, you know, without a metal head and fletching, it’s probably not worth the effort. And even with the skeins in poor shape, we still shoot further than I’d care to send any men to retrieve the bolts.”

Suppressing a sigh, Caelius answered, “Just do the best you can, Quintus. Nobody can ask more.”

Silently, Fulvius nodded then tramped off to see to the tightening of the skeins on one of the further scorpions. He felt the skein with his fingers, then flicked his forefinger at it, several times in different places. As he did, he muttered under his breath various curses aimed at certain gods and goddesses, and especially Tempestas, which Caelius feigned not to hear.

The first spear, led by Thiaminus, suppressed a smirk and continued on to the thicket within which cowered the camp prefect, Ceionius.

Without stopping Caelius saluted the legion’s eagle, with its plate underneath reading “XIIX.” Even as he did, he wondered, Should I have a fire built so that we can at least keep it and the imperial images out of the barbarians’ hands? Or at least get one ready we can torch off at need and toss the eagle into? Well, first things first.

With an audible sigh, Marcus entered the thicket. He noticed immediately how old Ceionius had gotten.

“Sir?” Marcus asked of the camp prefect, the praefectus castrorum, inside the thicket. He kept his voice carefully neutral, lest his contempt for the man shine through. This was made slightly easier by the sight of Ceionius’ ears, sticking preposterously far out from the sides of his helmet.

“We’ve got to surrender,” said Ceionius. The terror in the man’s voice was palpable. “We haven’t got a chance, not a chance, Caelius. We don’t even have enough food to march to a river.”

“Are you out of your fucking mind?” asked the first spear, heatedly. “Don’t you remember what the Germans did to Legio Five when they destroyed it twenty-five years ago? They crucified the survivors, the lot of them. We’re not surrendering shit.”

The words seemed to go in one of Ceionius’ ears and out the other. In any case, he acted as if he hadn’t heard. “Yes, that’s our only chance. Surrender. Then the emperor can ransom us. That’s it! That’s the only way!”

“The fucking Germans don’t care a fig for gold or silver, you idiot. There’s nothing much to buy with them, except what our merchants sell…and I don’t imagine they’ll survive the month. And the emperor is not going to give them what they do want, arms and armor. No, it would be a bad death or slavery for the lot of us if we were stupid enough to surrender.”

Now those words, Ceionius did hear. And didn’t like. “I outrank you, you pissant centurion and you will do as I order.”

“I will not, you overaged and overpromoted coward. We’ll stand here and fight. This is the bloody Eighteenth Legion; not a man will obey you.”

“They’ll obey or they all will find themselves decorating a cross, and you, too, you insubordinate son of a whore.” At this, the camp prefect drew his gladius, not so much with intent to do harm as a form of punctuation.

No matter, thought Marcus Caelius. He gave Thiaminus a quick glance. The former slave shrugged, You know what’s best, boss. And, at least, since I’m not a slave anymore, they won’t torture me for testimony.

This is hard, hard, thought the first spear. I can remember better days with Ceionius. Sharing wine. Telling stories, some of them pretty tall ones. What happened to turn a former first spear centurion into such a…such a…well, frankly, such a girl? If I let this, this girl out to start giving orders to the troops some will obey. Others won’t know what to do. We’ll be weakened and then destroyed without even a decent fight. So…

Caelius’ hand leapt to his gladius. In a single, seamless motion the sword then leapt from the scabbard to Ceionius throat. A quick and deft pull to the prefect’s left completed the destruction, slicing neatly through both a carotid and a jugular. Blood gushed to fall to the muck below, the softness of the ground dulling the sound. Ceionius fell equally silent, only the clattering of his armor and the phalerae adorning it making any sound. And the wood of the thicket and the mud below absorbed that.

Gently, Caelius took one knee beside the body. He wiped his gladius on Ceionius’ tunic, where it showed past his right shoulder, then re-sheathed the blade. Gently, almost reverently, Caelius used the same hand to close the prefect’s eyes.

“He was a fine soldier once. Let’s see if we can’t make sure that’s the part people remember.”

“I saw it all, Centurion,” said Thiaminus. “He was clearly out of his mind, lunging at you like that. Why, you couldn’t help yourself.”

Caelius smiled and said, “You’re a shitty liar, Thiaminus, but I appreciate the thought. No, if it comes to it, I’ll just tell the truth, that he had to be killed to put an end to pusillanimous conduct in the face of the enemy. But I hope the question will never come up. I’d prefer he be remembered for the soldier he was, once upon a time.”

“Now come on, we’ve got a line to troop.”

Stepping lightly from the thicket, Caelius told the aquilifer, “The camp prefect is indisposed.” Which is, come to think of it, as true a statement as has ever been. “Come with me. Let’s see if we can’t find some opportunity for you to earn your four hundred and fifty denarii.”

It was said lightly, with a grin, which prompted the aquilifer, one Gratianus Claudius Taurinus, to likewise grin and answer back, “But however will you earn your thirty times as much, Top?”

Marcus looked about, then seemed seriously to consider the problem. Rubbing his chin, thoughtfully, he answered,“Well, let’s see; thirty thousand Germans, give or take…at a denarius apiece, butchered, skinned and cleaned…that’s thirteen thousand, five hundred for me to kill and butcher. Meh, all in a day’s work. Let’s call it another sixteen thousand for the legion and auxiliaries, two and a half each…and so you’re going to have to murder nearly five hundred of the bastards, yourself. You up to it, Claudius? I’d hate to have to have your pay docked.”

“Fuck, yes, Centurion!” The aquilifer grinned even more broadly under the lion’s head draping his helmet; the creature’s skin cascading over his shoulders and down his back.

“Good lad; knew you were.” With a hearty clap to the aquilifer’s shoulder, Caelius said, “Well, come on then, let’s go see to the troops!”

Marcus deliberately steered his little party away from the tribune and towards as assemblage of refugees and the advanced party from the Seventeenth, resting their leather-covered shields while standing in ranks and being harangued by a senior centurion of their own.

Earthy, bragging, and to the point; that’s what they need to hear. Caelius headed over to listen for a bit…

“…You pussies are not going to embarrass me and the rest of the legion in front of the Eighteenth, d’ya hear? Yeah, we took it in the shorts for a bit, and, sure, you need a moment or two to catch your breath, but we’re going to take a piece of the line and give some of the boys from the eighteenth a little break. We going to get organized. We going to scout, and, soon as we can, we’re going back to get our comrades and our eagle. Oh, and our tents and our whores. Any fucking questions?”

The centurion from the Seventeenth caught a glimpse of Caelius and the eagle. He ordered a more junior centurion up, then trotted over and reported in: “First Order Centurion Quintus Silvanus, Seventeenth Legion.”

“I don’t think we’re going to be able to go back and save the Seventeenth,” said Marcus, leaning in and whispering. “Wish to Hades we could.”

Silvanus’ voice was full of grief. “I know that. You know that. But the troops don’t know that, and they need some kind of hope to hang onto. Hell, we’re all going to die but we can at least keep fighting until the Germans finish us off. Now where do you want us?”

Before Caelius could answer, Silvanus pointed and said, “By Vulcan’s blue balls, that’s some of our men. Those are our white shields.”

Caelius’ gaze followed the other centurion’s pointing finger. He saw, staggering out of the woods to the east, several hundred, at least, of the legionaries of the Seventeenth, some likewise with white-painted scuta, beset on all sides by Germans content to throw their primitive javelins and whatever rocks they could find, plus the occasional flint axe. More Germans beset the front ranks of the cohorts of the Eighteenth, with the Germans’ backs to the new refugees.

Before Silvanus could ask for permission, Caelius said, “They’re yours; go get them, as many as you can. Don’t get massacred in the getting, though.”

“Yes, Top! Thank you, Top!”

To Thiaminus, Caelius said, “Go get a couple of the medical types here to do triage when Silvanus brings his lost sheep home.”

“Yes, sir,” answered the freedman, who then ran off for the field hospital.

Meanwhile, turning to his ad hoc cohort from the Seventeenth, Silvanus bellowed, “All right, you pussies, you see it yourselves. Those are our men. Forward…march….At the double, follow meeee!”

Meanwhile, Caelius and Claudius bolted ahead of Silvanus for the cohorts that stood between the new refugees and the more organized refugees under Silvanus. When they arrived, Marcus knew there was no time to follow the niceties of the chain of command. Ordinarily, he’d have given the order to the senior centurions of those cohorts to let Silvanus’ men pass, But, since there was no time, he just shouted out, “You men know my voice. When I give the order, I want you to shift right, those who are uncovered, to cover down by files. Yeah it’s tough with the Germans on you like a stud on a bitch, but…no more explanation; Cover….DOWN.”

Automatically, the men of two cohorts shifted right, leaving about half the Germans facing them a little nonplussed. Almost instantly, a wave from the Seventeenth surged through the gaps, bowling over Germans and not even bothering to finish them off. That didn’t matter, though, as the red-shielded men of the Eighteenth were more than happy to stab and slice as much as needed to finish off the discombobulated barbarians.

Caelius took careful note of Silvanus’ approach to unruly Germans. He attacked with maybe three overstrength centuries, line abreast, and six ranks deep. They all struck to the right side of the approaching mob of fugitives from the Seventeenth.

The Germans were a brave people; Marcus hated their guts, for the most part, but still could concede the truth of that. But they weren’t idiots; absent some signal advantage they had less than no interest in standing up to a metal wave sporting razor sharp teeth coming on at the double. Casting whatever javelins and axes they may have had left and to spare, unencumbered by armor, they took to their heels to await a better opportunity.

Silvanus continued driving the Germans back and to the flanks until he reached the rear of the mob. He continued then another fifty paces to make sure the Germans were continuing to run, then had his group execute a smart about face, to charge down on the barbarians besetting the other side of the mob. These took off, too, and perhaps that much faster for having seen their fellows on the other side routed. With the mob now free of harassment by the Germans, Silvanus formed his men on line, in a loose order to allow the mob to pass through. This they did, some running, some limping, and some being helped by their fellows. As the last of them passed, the centurion began giving orders for the centuries to leapfrog back to the safety of the Eighteenth, but moving slowly enough for the mob to keep that one critical step ahead.

The Germans began to cluster and come on, then, but tentatively, as if expecting the legionaries still in good order to charge them or even to hurl some of those frightful heavy javelins they usually carried.

While Silvanus kept his little command in hand, Marcus met the refugees as they filtered through the lines of his own cohorts. He wasn’t especially bothered by their wounds, their blood, and the occasional legionary trying to hold his guts in with both hands. No, what he found shocking was how few of them still carried their scuta, and how every last one of them had lost their furcae and sarcinae, their packs and the poles to which those packs and other necessary gear was affixed.

Bad sign. Very bad sign.

“Sit down, boys,” Marcus ordered, “but over there where the medics can see to you.” He gestured in the general direction of a cloth standard attached to a pole, the standard showing the medical symbol, the caduceus. Marcus also noticed that the legionary haruspex, Appius Calvus, what a much later generation would have called a “Chaplain,” of sorts, was standing by with the medicos, presumably to lend a hand.

This one isn’t bad, thought the first spear. I’ve seen some that were just lazy shitheads, but he’s willing to pitch in where he can. And the troops are pretty sure he’s really got the sight, to boot. After all, he did warn the legate about Arminius, even though he probably got the idea from Segestes.

Turning back toward Silvanus, he saw the men of that makeshift cohort filtering back through the lines of the Eighteenth.

“You saw,” said Silvanus, obviously meaning the wretched, demoralized state of the refugees.

“I saw,” agreed Marcus Caelius.

“A day of rest,” said Silvanus, “and some re-equipping, and they should be fine.”

“I agree but…” A murmur from the lines distracted both men. They looked generally eastward, to where Varus and the bulk of the army lay, entrapped, and saw smoke, thick, dense smoke, rising upward and billowing to the south. The setting sun illuminated the smoke in a way that, under the circumstances, was positively creepy.

“Fuck,” said Silvanus, “that’s not some random bit or arson from the Germans, not in this weather. They’re burning the baggage to keep it out of the Germans hands.”

“Fucked,” corrected Marcus Caelius.

A German, one-eyed and bright blonde, strode up to Caelius and Silvanus. He carried his crested helmet under one arm, letting the rain run down his golden locks. He towered over the two Romans. The German wore Roman armor that hadn’t been looted, carried a Roman sword, was clean shaven in the Roman manner, and wore his hair close-cropped like other Romans.

“Hail, Flavus,” said Caelius and Silvanus, together.

“Ave, Primus Pilus,” answered the German. “Ave, Centurion.” His Latin was flawless and without accent, except that of the upper crust of Rome, the city.

Cutting to the chase, Caelius asked, “Can you tell us what happened?”

The German nodded and sneered, then said, “Well…it all began when my father knocked up my mother and then neglected to strangle my bastard treacherous brother in the crib. Or it could be that he acquired his lust for power from you, when Rome was educating us, as boys. But you mean more recently, yes?”

“Yes.”

“I don’t know how long my brother’s been planning this; years, I think. Maybe ever since he saw how poorly the legions fared in dense woods down in Pannonia. Maybe longer still. He always kept his own counsel.

“In any case, he somehow managed, under the guise of diplomacy on behalf of Varus, to form an alliance of tribes most of which hate each others’ guts but apparently hate Rome and civilization more.”

At the mention of Varus’ name, both Caelius and Silvanus spit.

“Don’t hold the governor too much to account,” Flavus said. “If Arminius could fool his own brother, how much chance did a near stranger have to understand him?”

“No, excuses,” said Caelius. “It wasn’t your job to ferret out Arminius’ intentions, even if – maybe especially because – he was your brother. It was his.”

“Maybe,” Flavus conceded. He then laughed. “They’ll be fighting amongst themselves ten minutes after they finish us off, you know. That’s a good deal of why half of my tribe supported Rome from the beginning. The carnage we Germans inflict on each other is just appalling.”

Caelius found himself a little warmed by the German’s use of “us.”

“Maybe not,” said Silvanus. “not this time. Maybe they’ll all march west and then south, as the Teutons and Cimbri did in the time of Marius.”

“True,” said Flavus, bitterly. He had learned truly to love Rome during the time when he, like Arminius, had been what amounted to student hostages, since early boyhood. “Hades, that is true. What the hell are we going to do; the forces on the frontier must be warned!”

“How reliable is your deputy,” asked Marcus Caelius, “the big bruiser in the bear skins under his lorica?”

“Agilulf? I wouldn’t trust him to fight Cherusci, men of our own tribe, but he’d happily gut any other Germans. Buuut…he doesn’t speak all that much Latin and doesn’t know much besides line up and poke the man in front of you. On the plus side he keeps good discipline. Which gets into what you asked me originally; what happened?”

“I didn’t see it myself, mind” the Romanized Cherusci said. “Got it from some stragglers and runaways. But my brother had command of the German auxiliaries nearest to Varus, a whole cohort of them. Big cohort, too, eight hundred men, maybe. At a signal from him – no, I don’t know what the signal was – my countrymen came pouring out of the woods in their thousands. Right after he gave the signal, he gave some orders and, instead of forming up to face north and south, that cohort faced east and west and drove into the legionaries that had been ahead of and behind them. Instant chaos. Instant break in the line. Instant inability for Varus to give any commands to Nineteenth Legion, too. Varus did manage to escape to the Seventeenth, but they were so distorted by the attack he can’t have lasted too very long.”

A sudden thought came to the German. “Centurion, have you talked to any of those men from the Seventeenth you saved yet?”

“No, not yet,” Silvanus answered.

“Talk to them. I’ll bet you that they aren’t just some stragglers and runaways, but that they’re just about every man that’s still free and alive from the Seventeenth.”

“Shit!” the centurion cursed, seeing the truth of what Flavus had said. “My legion is gone, that smoke from the baggage from some fires set by the last survivors.”

“Cool men, then,” Marcus Caelius said, consolingly. “Brave ones, too, to keep their heads about them and try to help us as much as they could.”

“Hmmm,” Caelius continued, “if the Nineteenth had already gone under the Germans would be on us like flies on shit. They aren’t, not yet, so the Nineteenth still stands.”

“That seems likely,” both Flavus and Silvanus agreed. “So what?”

“So maybe in the morning we can fight our way up over that hill, flank the Germans, and bring the Nineteenth out to us. Silvanus, if I leave you three cohorts, both the auxiliary cohorts, and your own men plus the hundred or so from the Nineteenth who were with us, do you think you can hold this…you should pardon the expression, camp?”

Without hesitation, the centurion answered, “No. The perimeter is too long, the woods too much in and around, and the camp itself is much too weak. Leave me five cohorts, plus the others, and I can. But that won’t leave you much, not enough to get through those Germans behind their wall. Especially when the ones further east join them.”

“Well,” mused Flavus, “what if I disguise myself as one of the tribesman? There’s plenty of bodies here. Some skins. A round shield. A little war paint. I do speak the language, too, after all. So we disguise me up and I make my way to the Nineteenth, tonight. I tell them to strike southwest, across that hill, to link up with you. Then, somewhere near the summit, you link up and march back to here. I can probably scout out the best place for them to attack, though I doubt I’ll get back in time to do much to help you.”

“Fuck it,” said Caelius, suddenly. “Fuck the camp, too. It’ll be all of us going over that hill. Yeah, the trees will break us up some, but at least we won’t be strong out in a file of twos and threes. I saw it when you went out to bring your men in, Silvanus; the Germans don’t like facing legionaries in good order for beans.”

“The wounded?” asked Silvanus.

Marcus Caelius was a hard man but even he balked for a moment at the prospect of leaving their wounded to the tender mercies of the barbarians who would flood the camp once the legions and its attachments marched off. But then…

“Few hundred wounded. Okay, maybe closer to a thousand, but half of those are walking wounded and can still fight. On the other hand, five to eight thousand legionaries and auxiliaries to be saved. The five to eight thousand have it. We strike at first light. We’ll load the non-walking wounded into whatever wagons we have and the walking wounded can guard them. Best I can do.”

“Sun will be in our eyes,” Silvanus objected.

“Leaving aside that the trees will shield us from the sun, Flavus, will this rain keep up?”

“This time of year? This part of Germania? Nearly certain to.”

“All right, then. Flavus, you disguise yourself and slip out after the sun goes down. Find the Nineteenth and ask for Lucius Eggius; he’s a good man. Explain what we’re going to try, from our end, and tell them where and when to attack. Silvanus, you go get as many of your men as can be used, including the ones you just rescued. I want you to put on a good show, that’s all, not to slug it out with the Germans.”

“Before you leave, Flavus, get your Agilulf and make him understand to follow Silvanus. Silvanus, I want you to stretch out in as solid a line as you can make it from the swamp to just west of the edge of the Germans’ wall, to guard our flank, as it were. Meanwhile, I’m going to go explain to the tribune what his orders will be – oh, he’s a good lad, and willing enough, but new – and then see that he gives those orders to the other senior centurions. Finally, Flavus, if this doesn’t work steal a horse and get to Aliso. When you get there warn the commander there – I think it was Lucius Caedicius – about what’s coming. It will be up to him to decide whether to hold the fort or pull back behind the Rhine. If this works, we’ll strike for the open agricultural country in the middle of Cherusci land, resupply ourselves by any means necessary, then to the Lupia River.”

If there was anything Flavus wanted in like beyond the glory of Rome, it was that the legions should stay far far from Cherusci lands. What he hadn’t mentioned to Marcus or Silvanus was that his and Arminius’ father, Segimerus, was also arrayed against the Romans. If they found that out, and they might, and they found their was to the land of the Cherusci, even these woods might not provide enough wood for all the crosses.

Flavus thought and he thought quickly, then said, “No, the bulk of the enemy are to the east. There is probably another ambush site prepared there, too. Morevoer – give my treacherous brother his due – I’d be bloody amazed is there were not more than one, and a like number to the west.”

“So what do you suggest?” asked Caelius.

South,” answered the Roman Cherusci. “South for sixty miles. Yes, you may go hungry going that way, but once you reach the river you can cross it, to put it between you and my brother’s army. Wait, you do have engineers with the legion, still, right?”

“We do,” Caelius answered. “For that matter, the advanced parties from both the other two legions were about a third engineers.”

“Right,” Flavus enthused. “You can bridge it, burn the bridge after you cross, and then be supplied by water as you march to the Rhine.”

“I think he’s right,” said Silvanus.

Thank you, Odin and Jupiter, thought Flavus.

“Makes enough sense,” agreed Caelius. “We’ll do that. But first we need to extract the Nineteenth.”

From the other side of the camp came the cry, “Here they come again!”

*Tom has his own substack at: https://yourrightwingdeathsquad.substack.com/ SAH*

c4c

LikeLike

Looking forward to giving Col. Kratman (ret) more of my money when this is finished and published.

LikeLike

(grin)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, please take my money. Thank you.

LikeLike

Interesting. I wonder how it would read translated into Latin? /grin

LikeLike

Tacitus in Igpay Atinlay? (Cicero is much better in Igpay Atinlay. Not that I ever did that, mind, but so I’ve been told.)

LikeLike

The first sentence courtesy of Google translate

Is it any good (the translation, I liked Col. Kratman’s text :-) )? caelo plumbo is literally a sky of lead, is that a Latin saying? I doubt it. I also wonder about the addition of et (and) between miserorum (miserable) and trementium (trembling). Not sure a Latin speaker/writer would bother with the and. Also effusus est seems to be current tense or a mangled version of english imperfect but poured seems to be past or maybe imperfect ( Mrs Emmerson my 7th and 8th grade English teacher is now rolling in her grave)? And last and most subtle is the order of descriptions. In English we would say 20 large purple people eaters not purple large 20 people eaters there is an implicit order of descriptions, Google has left the order of the descriptors the same as in English which may or may not make sense.

Google Translate seems to go with mostly a word for word translation(formal vs dynamic). It is still in dancing bear mode, i.e. it is amazing that dances at all let alone how well, (or in how many languages).

LikeLike

Well, it looks like gray is usually “canus” (macron over the a), like gray/white hair (there’s also semicanus for half-gray and praecanus for very gray), glaucus (which is also sea green, blue, and even red like an ocean sunset), and caesius, which means “gray sky-colored” (as opposed to caeruleus, “sky-colored”, which is blue or light green or a lightish pale color).

Gray eyes are caesius.

There’s also cinereus or cineraceus, ash-colored; pullus, dark gray or dusky; ravus, tawny or gray; and griseus, which was medieval Latin and too new.

HOWEVER, “plumbeus” is indeed the adjective meaning leaden, in both the sense of things made of lead and things the color of lead. It’s also the adjective to describe blunt people, heavy things, and stupid people. Or just things that are of poor quality, like a leaden age as opposed to a golden age.

LikeLike

I suspect that as AI continues to make inroads in computing that translations may become more grammatically correct, rather than just word for word correctness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anyone know of any AI that has been trained up on classical Latin?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds right to me; but what do I know? I was supply and can only tell a gladius from a pilum.

LikeLike

I’ve been reading the ACOUP blog (https://acoup.blog/) and recognize both gladius and pilum. Interesting battle here… (Readies wallet for the release.)

LikeLike

The interesting bit is that haruspices took a good chunk of their auguries “ex caelo,” from the sky. But that’s usually about thunder and lightning, and what direction it comes from, in relation to the place set out for the augurers to work.

The “augurale” was the place in an army camp where the haruspex did his official divinations. I had no idea this was part of the standard planning and layout, but it was.

(Obligatory pointing to the Gospels, where I’m sure all the thunder was unnerving to the Romans from Rome.)

LikeLike

I really, really like this snippet. It’s very vigorous and alive, and all the historical details serve the story instead of bogging it down. And it’s a very human story. Everybody has things they want and fear, and priorities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you folks like it, so far.

Thanks, Sarah.

I actually have two substacks. One is “The Care and Feeding of YOUR Right Wing Death Squad,” which, no, is not a how to manual but a fairly desperate plea to get our frankly wildly insane domestic left to chill before their activities beget right wing death squads.

The other, Substack Home – Tom Kratman’s Lines of Departure, 2023 , is where I repost columns from my old everyjoe column (mostly for pay) and further snippets from 9 A.D., entirely for free.

I’d been musing on this book for years. Finally woke up in very late February with the thought, “I’ma gonna do it.”

By the way, the opening? Think: ‘It was a dark and stormy night.” Yeah, there was actually nothing wrong with “It was a dark and stormy night,” and, where possible, I like to remind people of that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The book I’m finishing. After 40 some years I thought “I’ll just write it.”

Next up is something I’ve been toying with for 35 years.

Because now we can just do things. :)

LikeLike

Exactamundo.

LikeLike

Col., the link you provided to your other substack comes back with “You’re logged in as [redacted], but this page is private. Try signing in with a different email, or letting the author know they’ve linked to a private page.”

Rather than trying this back window more forcefully, Is there a front door link?

LikeLike

Okay, I used some of those elite web fu skills my employer still somehow believes I have and got there via:

https://tomkratman.substack.com

LikeLike

I hate to think how many people are ready to snap. Just wandering my corner of TwiX this morning has *my* blood pressure up, though not nearly enough for violence, for which I am woefully unequipped.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much this.

LikeLike

A NextDoor post where someone was at one of the local downtown adjacent dog parks (Alton Baker – across the river from downtown center, huge river city park). People started hassling a dog handler who was in the fenced dog park. To the point where one over aggressive person entered the dog park to escalate because the dog handler would not engage. As soon as the aggressor entered the fenced area (through two gates), handler called dog, leashed the dog (was a large dog, not because aggressive breed, but because of the aggression of the individual and group), and tried to leave. Was not able to … UNTIL handler showed was carrying concealed (never pulled gun, just flashed that was carrying). Interestingly enough comments (that were there when I read the post so could have devolved since then) were supportive of the handler and how the situation was handled, including showing the concealed. This is Eugene! The aggressive individuals (not stated if homeless, but not unlikely) not a surprise (Eugene!). But the support for someone not only carrying concealed, but posting in writing that they actually showed having it to get out of the situation, and Got Support from others in writing? In Eugene? That was a surprise.

LikeLike

Every Russian novel is full of weather reports, as a mood/atmosphere indicator. Everybody else does it too, but Russian weather is just so much more extreme. (And the sentences are so long and Victorian at those points, even when the dialogue consists of one- and two-word sentences.)

LikeLike

Nice!

Looking forward to spending some money …

LikeLike

What a wonderfully unexpected thing to find at the blog. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quintilius Varus in Germania, eh? As the Jedi are wont to say, I’ve got a bad feeling about this…

LikeLike

“Varus, bring me back my legions!” Or so Augustus was rumored to cry as he wandered on sleepless nights.

It’s a creepy battlefield, especially on a cold, rainy day with no other visitors around. It made the hair on my neck stand up, and I was twitchy and uncomfortable during the entire visit.

LikeLiked by 1 person